In 2007, Smithfield Foods, the largest pork producer in the world, made a startling declaration: It would begin phasing out “gestation crates,” an extremely inhumane practice that involves confining mother pigs to fenced-in areas barely larger than their bodies, where they lack any room to turn around.

It’s hard to adequately convey in words the brutality involved in gestation crating. Ian Duncan, an eminent scholar of animal welfare at the University of Guelph, has described it as “one of the cruelest forms of confinement devised by humankind.”

Unsurprisingly, Smithfield’s announcement was met with near-unanimous praise from animal welfare advocates. So too was its January 2018 announcement that it had, indeed, succeeded in transitioning pregnant pigs from gestation crates to a “group housing” model with a much more limited role for crating.

But in a new report, the animal welfare group Direct Action Everywhere (DxE), which infiltrated several Smithfield facilities in North Carolina between June 2017 and February 2018, alleges that Smithfield still uses gestation crates for pigs that are clearly pregnant, as well as pigs that have already given birth.

“It’s not uncommon to see baby pigs in gestation crates,” Wayne Hsiung, DxE’s chief organizer and one of the investigators who visited the Smithfield facilities, says. “We absolutely did see mother pigs giving birth in gestation facilities.” The cramped conditions of those facilities create a huge risk of crushing death for piglets.

DxE took copious photos and video from the facilities it investigated. The group, a loose, decentralized network of activists founded in the Bay Area in 2013 with a stated goal of using “nonviolent direct action to end the exploitation and killing of all animals,” specializes in undercover investigations exposing poor conditions at farms, particularly farms making claims to humane treatment, and has released a bevy of similar reports on other farms across the country in recent years.

What DxE alleges occurred in the North Carolina facility would be in clear violation of Smithfield’s promise to eliminate the use of crating for pregnant pigs. The company has stated publicly that sows on its farms will remain in crates while being inseminated, then moved to group housing with other mother pigs, and then moved to bigger “farrowing crates” with their piglets once they’ve given birth.

The DxE investigation suggests that process is not being followed. If it were, then mother pigs would’ve been moved from crates into group housing months before giving birth. Instead, Hsiung and his team allege that sows remained in gestation crates so long that they wound up giving birth there, with fatal consequences for their piglets.

In a statement and phone conversation, Smithfield argued that all the animals photographed by DxE were either in breeding stalls or in farrowing crates, and that pregnant pigs were not left crated.

“We have immediately launched an internal and third-party investigation of the sow farm in question. Once complete, we will share these findings and swiftly address concerns, if any,” Smithfield spokesperson Keira Lombardo said in the statement. “The health and well-being of these animals were compromised when those claiming to be animal care advocates trespassed onto farms, violated our strict biosecurity policy that prevents the spread of disease, and stole our animals. These individuals are not animal care experts, but activists who continuously risk the lives of the animals they claim to rescue.”

Mary Battrell, a Smithfield swine veterinarian, argued that the crated animals seen in DxE’s photos and video were either in farrowing crates or not confirmed pregnant and placed in breeding crates. “There’s an [artificial insemination] harness on the crate which means it had just gotten used,” she said, referencing the below screenshot from the video. “The blue marks are our typical breeding mark. They just got bred.”

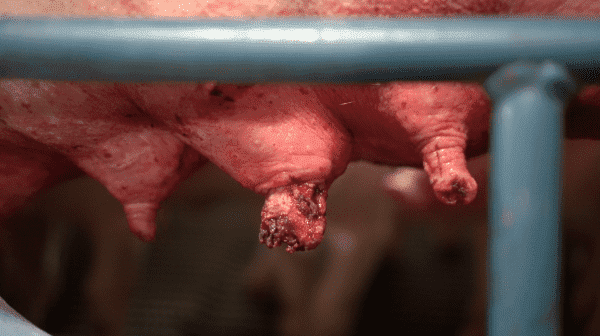

However, Battrell conceded she was disturbed by the photo Direct Action Everywhere took of bloody nipples on a sow:

This image contains sensitive or violent content

Tap to display

“Unless there’s blood in the crate,” she explained, this type of injury “is kind of hard to find.”

DxE’s Hsiung stuck to his account of ubiquitous crating, adding, “We have been in dozens of Smithfield gestation facilities over the past year, and we’ve seen thousands of mother pigs in crates — and hardly any outside of them. Smithfield’s press release from 10 years ago indicated that it would be phasing out crates, not used for a different purpose. They are conceding now that did not happen.”

As evidence, Hsiung points to the fact that he saw “plenty of pigs with green and pink marks in gestation crates. (We also saw black marks in crates.) The pink mark is the same color as the pigs in the farrowing crates, suggesting that they are moving straight from gestation to farrowing.”

“In virtually every instance where we’ve exposed a factory farm, they claim there is a mythical ‘humane barn’ where the animals were well treated,” he continued. “The reality is that they must do this because the public does not have a stomach for animal torture.“

Battrell and Lombardo strenuously objected to this argument, and say pink paint was used for different purposes in the breeding stalls and the farrowing crates. One stripe, they say, means the sow has been inseminated once, two that it has been inseminated twice. “The fact that the sows in the breeding stalls and the sow in the farrowing crate both have pink paint is meaningless,” Lombardo wrote in an email. “The farms usually have no more than three different colors, so it is possible that this farm was using pink in both the breeding barn and farrowing barn. It does NOT mean that we are moving sows directly from breeding stalls to farrowing stalls.”

The horror of pig crating

Sows are, as you might imagine, central to pig farming, as they produce successive generations of pigs to be harvested. They spend most of their lives pregnant or nursing, with each pregnancy lasting 112 to 115 days, or about four months. In the gestation crate system that Smithfield claims it has abandoned, they’re placed in the crates where they’re basically immobile.

The floor is slatted so that when the pig pees or defecates, their excrement and urine falls below them. The pigs don’t literally live in their own shit; they just live above it and breathe it in constantly. Hsiung claims that he has seen, at Smithfield facilities, piglets get stuck in these slats after their mothers had given birth, after which they likely fell to their deaths. (In pasture-based farms, pigs can defecate on soil, which has the side benefit of serving as a natural fertilizer.)

When they deliver, sows are moved to “farrowing crates,” which are only slightly more roomy and are designed to prevent the mother from crushing her new piglets. Once the piglets are weaned, the mother is inseminated anew and the process repeats all over again. After a number of these cycles (between three and four on average in the US), the mothers are killed.

Pigs are remarkably intelligent animals. They have good memories, love to play and explore, recognize each other, and have sophisticated social lives. Purdue animal scientist Candace Croney even taught pigs to play video games. (The pigs loved it.)

So imagine an animal like your dog, but perhaps smarter, forced to live cheek by jowl with dozens of other animals, unable to turn around or play or see any of the world outside their immediate surroundings. That’s the life of mother pigs in crates. The crates in the photo below, the company claims, are breeding crates, which offer similar confinement to gestation crates:

Being forced to live in such tight quarters tends to leave pigs with scrapes and lesions, which can become infected, resulting in cysts and abscesses like these on the hind leg of a sow:

This image contains sensitive or violent content

Tap to display

Pigs typically revolt against this system. When offered a chance to leave crates, they usually do, and refuse to go back in. Once confined, they exhibit nervous tics and self-harm characteristic of animals in distress.

When the Humane Society of the United States conducted an undercover investigation of Smithfield in 2010, after the company made its pledge but before its self-imposed deadline for phasing out gestation crates, the group found that “some sows had bitten their bars so incessantly that blood from their mouths coated the front of their crates.” The Humane Society’s investigator pointed out one sow who has a “basketball-sized abscess on her neck.” The barn manager said to ignore it, and then “cut the abscess open with an unsterilized razor.”

(Smithfield responded to that exposé by commissioning a formal investigation and firing three employees it found liable for animal abuse but who hadn’t been disciplined until the Humane Society forced their hand. It also attacked the Humane Society investigator and painted his findings as overblown.)

“The way I look at it is: How would you like to live in an airline seat?” the animal welfare expert Temple Grandin once told a reporter about gestation crating. Donald Broom, an animal behaviorist at Cambridge University, calls it “much worse than severely beating an animal.”

Conditions aren’t much better for the piglets jammed in there with their mothers. The Humane Society investigation found that “some piglets born prematurely in gestation crates fell through the slats and died in manure pits.” The investigator also saw Smithfield employees throwing piglets onto trucks rather than carrying them.

In their book Compassion by the Pound, the agricultural economists Jayson Lusk and F.B. Norwood used a quantitative model to compare the welfare outcomes of different confinement systems. On a scale of 0 to 10, gestation crates got a 0.66, making it almost perfectly inhumane. “The only system that performed worse than the gestation crate system was a system where sows were literally tethered in place,” they write.

Most Americans have, when given a chance to vote on the matter, chosen to outlaw gestation crating. Arizona, California, Florida, and Massachusetts have all passed ballot initiatives banning or phasing out gestation crates, and another six states have passed legislation or regulations doing the same. No initiative banning crates has lost at the ballot box, and they typically win by large margins. (In 2006, Arizona’s ban passed 62 percent to 38 percent; in 2016, Massachusetts’s passed with 78 percent support.) As of January 1, 2013, the European Union has enacted a partial ban too.

Notably, the 10 states that have banned gestation crates house less than 7 percent of the 68 million pigs living in the US. Iowa, North Carolina, and Minnesota, which together house more than half of the country’s pigs, still allow crates. Iowa and North Carolina also have “ag-gag” laws that impose civil or criminal sanctions on activists who seek or gain employment with an eye to exposing animal mistreatment.

Corporations have also taken actions on their own, with Smithfield’s 2007 announcement being one prominent example. In 2012, Burger King committed to stop purchasing pork from facilities that use gestation crates, and McDonald’s, which has used Smithfield in the past as a supplier for the McRib, has set 2022 as a deadline to end the use of gestation-crate pork. In 2015, Walmart urged its suppliers to cease crating. Smithfield’s example was hardly the only reason others acted, but its announcement added considerable momentum to the movement to end crating.

Wendy’s, Subway, Denny’s, Dunkin’ Donuts, IHOP, Kraft, Sysco, Chipotle, Safeway, Kroger, Target, and a wide array of other food/retail companies have made similar pledges. Animal advocates at groups like the Humane League and Mercy for Animals have, in recent years, increasingly relied on “corporate campaigns” pressuring meat purchasers to force animal welfare improvements, and have exacted a startling number of pledges covering millions, if not billions, of animals, including sows.

What Direct Action Everywhere’s investigation showed

But these corporate campaigns can only be successful if meat suppliers are held accountable for the pledges they make, and laws banning animal cruelty can only be effective if government agencies have the resources and inclination to enforce them. Direct Action Everywhere’s investigations have found time and again that companies fail to adhere to their own pledges, and state governments fall down on the job of enforcing the animal welfare laws they’ve passed in the past couple of decades.

Just last year, the group investigated another pig farm of Smithfield’s in Utah where they took video of “piles of dead baby pigs rotting in feces while others drank from bloody, mutilated nipples of sows.”

In 2016, the group conducted an investigation at a California cage-free egg farm that supplies Costco’s Kirkland brand and found “hens being attacked and even cannibalized by other hens due to the crowded, unnatural conditions. The investigators also found chickens struggling to breathe air dense with ammonia and fecal matter; birds covered in feces; hens with bloodied bodies from attacks; and the rotten bodies of dead birds among the living.”

In 2015, they found that Diestel Turkey Ranch in California, which received Whole Foods’ absolute highest “Step 5+” animal welfare rating, housed turkeys that were starving or seriously ill, and left carcasses among living turkeys long after they died. (Targeted farms generally responded by accusing DxE of breaking and entering and alleging that the videos were unrepresentative or showed images out of context.)

The new Smithfield investigation is the latest in this tradition. Conducted after Smithfield’s announcement that it had phased out gestation crates, the investigation claims that the crates remain the norm, at least at the North Carolina farm, including for pregnant pigs and pigs who’ve just delivered and were supposed to be moved to roomier farrowing crates.

DxE claims the investigation also uncovered:

- Numerous cases of gaping wounds and infections on pigs that appeared to be caused by close confinement

- Pigs whose skin appeared infected

- Pigs with infected cysts

- Sows whose nipples have been injured sufficiently that their piglets are nursing on pus and blood

- Dead piglets left rotting next to their living counterparts

- Plastic bags full of clipped-off testicles and tails from pigs

- Use of Carbadox, an antibiotic which is a known carcinogen and which the Food and Drug Administration has moved to ban

In a phone call, Battrell, the Smithfield veterinarian, conceded that the company still uses Carbadox and will continue to do so unless an FDA ban goes through. She also conceded that the company castrates and clips the tails of pigs without using anesthetic. She says there is no available anesthetic for the procedures, that castrating boars is necessary to prevent the meat from becoming too musky, and that cutting off piglets’ tails prevents them from biting each other’s tails.

So was Smithfield’s crate promise a lie? If Hsiung and DxE are correct that pregnant pigs and new mothers remained in gestation crates, that suggests that the company is not following its stated procedure, which calls for pregnant pigs to be put in group housing. The company strenuously denies Hsiung and DxE’s claim there.

But the company gives itself some wiggle room by stating explicitly that it crates pigs while they’re in the process of becoming pregnant. These practices definitely violate the spirit of their pledge to eliminate gestation crating, which, as Hsiung notes, did not specify that sows would remain crated for every waking moment outside of pregnancy — but Smithfield can argue that it obeyed the letter of its promise. On its website, Smithfield explains that while the sows are supposed to be housed together in groups while pregnant, they’re “artificially inseminated and housed in individual stalls until confirmed pregnant.” They’re moved to farrowing stalls with their piglets once they’ve given birth.

DxE alleges this process was not followed — that already-pregnant pigs were left in gestation crates, not moved into group housing once confirmed pregnant — but the company points to that process to explain why crated pigs remain in Smithfield facilities despite its pledge. They’re just in breeding or farrowing crates, not gestation crates.

“If you read the fine print of a lot of the press releases by companies that pledge to go cage-free on eggs or crate-free on pork, they often leave themselves some wiggle room in case there isn’t sufficient demand,” Lusk, the agricultural economist, says in an email.

“I can’t prove there aren’t pigs going into group housing somewhere,” Hsiung of DxE says. “You can’t prove a negative. It just happens to be that every farm we see is perfectly cruel.” (DxE opposes all animal agriculture but is particularly critical of the brutality of industrial factory farms.)

Hsiung estimates that he and other DxE members have, in person, investigated upward of 50 Smithfield facilities all over the country. While the latest investigation wrapped up after Smithfield declared its transition away from gestation crates was accomplished, the previous ones were during the transition, and Hsiung says he saw little evidence that the company was moving in the right direction. (See, for instance, this report from last year.)

Given the sheer number of facilities he’s seen, Hsiung argues, “The odds of [those facilities] not being representative are pretty low.”

Hsiung also notes that the alternative method, group housing, is not too much better than gestation crating. It’s an improvement, but it leads to increased conflict with other sows and results in confinement due to a lack of personal space rather than confinement by metal bars.

In Compassion by the Pound, Lusk and Norwood identify two superior systems to either group housing or gestation crating. One is called the “shelter pasture” system, in which pigs are given a natural outdoor environment with plenty of space to roam, but also protection from predators and a reliable source of food. This takes up a considerable amount of space and unsurprisingly is extremely uncommon; it roughly corresponds to the Stage 4 and Stage 5/5+ ratings for pork explained by the Global Animal Partnership, which conducts labeling for Whole Foods.

Lusk and Norwood also find good results for the “confinement plus” system, in which sows have limited access to the outdoors but plenty of space for themselves and their piglets and plenty of space to roam freely outside their lying area.

But Direct Action Everywhere’s investigations have found that even at farms that receive high ratings for humanitarian treatment, cruel conditions often remain — as in the Whole Foods Stage 5+ turkey farm where they found starved and dying turkeys.

The only way to ensure to avoid subsidizing animal cruelty, they urge, is to fundamentally revamp our animal protection laws. Until that happens, perhaps the only humane diet, the activists say, is one where we abstain from eating animals altogether.

Sourse: vox.com