Arizona teachers returned to class on May 4 after ending a six-day strike that closed nearly all of the state’s 2,000-plus schools. Educators returned to work after the state legislature gave them a 20 percent salary raise over three years and some extra funding for public education.

But there’s a catch: Lawmakers are going to make them and other middle- and working-class Arizonans pay for the raise.

Teachers had wanted legislators to raise business and income taxes on wealthy Arizonans to restore cuts to public education and boost anemic teacher salaries. Republicans gave in to some of the demands for more funding — but they’re not paying for the salary hike with new taxes on the wealthy. Instead, the legislature passed a fee on motorists and shifted most of the cost of desegregating schools from the state to taxpayers in low-income school districts. Those levies will largely hit working- and middle-class taxpayers.

The developments in Arizona fit into a broader pattern. Teacher unrest has roiled a handful of (mostly conservative) states: Arizona, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Kentucky. The protests are a response to decades of funding cuts for education and years of tax cuts that overwhelmingly benefited businesses and wealthy taxpayers. In each of these states, teachers called on lawmakers to boost funding for public education with higher taxes on corporations and the wealthy.

For the most part, the strikes have proven effective in forcing Republican lawmakers in those states to restore some of that funding. But these legislatures have fiercely resisted efforts to raise any taxes. And when they have given in, they’ve done so in ways that would disproportionately hurt workers who are struggling to make ends meet.

Arizona

Republican Gov. Doug Ducey signed a budget bill May 3 that gives teachers a 20 percent pay raise over three years. The plan will cost the state more than $600 million a year, and lawmakers don’t yet have a plan to pay for it all. Here’s how they agreed to pay for some of it:

- A new $18 car registration fee that is expected to raise $149 million a year. Such a fee is, of course, regressive — it will cost low-income families more than higher-income families because such a fee represents a larger chunk of the former’s income.

- A change in how the state desegregates public schools that should free up about $18 million a year in state money. Most of that cost will be shifted to homeowners, via higher property taxes in low-income school districts.

These two changes will not be enough to generate the more than $600 million needed to cover the teacher raises and new funding for schools included in the bill passed last week. Ducey is counting on optimistic economic growth projections to bring in more revenue to pay for some of it — something Republicans love to promise but have little control over.

In recent weeks, Ducey had proposed a plan to help pay for teacher raises that wouldn’t hike taxes but most likely would have taken money away from other parts of the budget, including aid for people with developmental disabilities and money to hire skilled nurses for Medicaid patients. Those potential cuts were not in the final spending bill. But if the economic boom doesn’t materialize, it’s pretty clear who will probably pay for the funding gap: not businesses or wealthy families.

Arizona voters could change that. The state has not raised income taxes since 1990, and other taxes have only been raised through ballot initiatives. A coalition of teachers and parents have launched a petition to add one to the ballot in November. The initiative, spearheaded by a progressive public policy group, would hike the income tax rate for workers that earn more than $250,000 a year or households that earn more than $500,000.

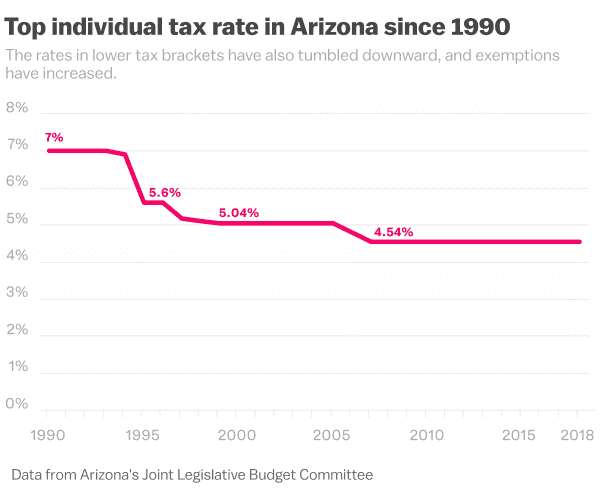

This tax increase would be the first time in nearly three decades that Arizona raised individual income tax rates. Top income tax rates have fallen since 1990:

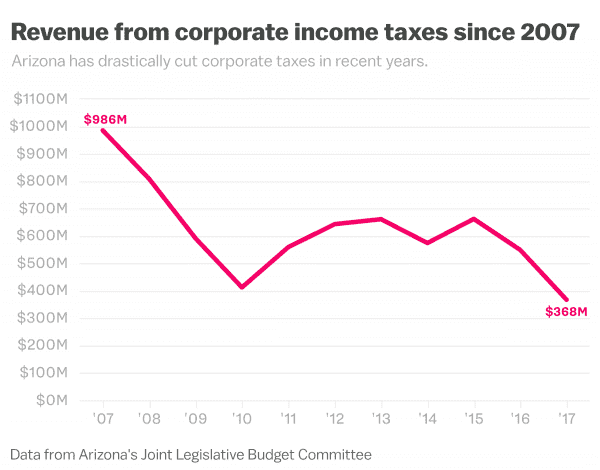

And in the past decade, the state has cut corporate taxes drastically. This, along with the recession, contributed to the state losing more than $600 million in revenue from businesses:

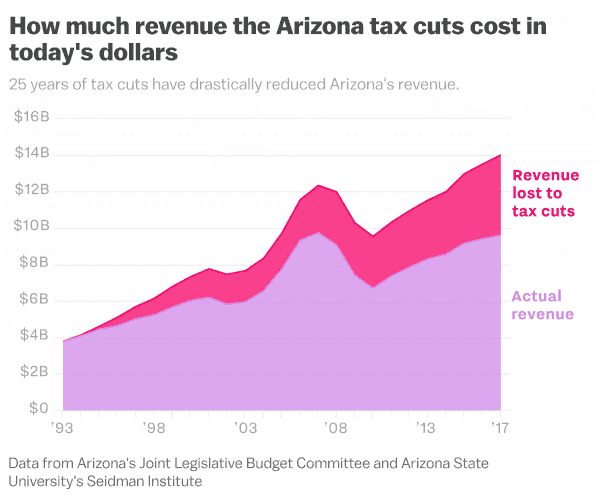

Put together, the past 30 years of tax cuts cost the state about $4 billion in revenue annually — and education has been hit hard because of it:

Since the Great Recession, $1.1 billion has been cut from the Arizona education budget.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma teachers got an average $6,100 raise in April after going on strike for nine days. Lawmakers also agreed to a smaller raise for school support staff and more than $60 million in extra funding for schools. But politicians refused to pay for the $479 million increase in education funding by eliminating the special tax deduction for capital gains investment income, as teachers had suggested, or by raising the tax rate on high-income earners. Instead, they agreed to:

- A 6-cent tax increase on diesel fuel and a 3-cent increase on gasoline. Fuel taxes are considered regressive because they make up a larger share of a low-wage worker’s paycheck than a wealthier worker’s paycheck. (There is, however, some debate about how much a gas tax hurts the poorest workers, who are less likely to own a car.)

- A $1 tax increase on cigarettes, which is also regressive.

- Expanding the type of gambling allowed in tribal casinos, which would bring in an estimated $22 million annually in new tax revenue. Casinos had lobbied for this expansion.

- A sales tax on online purchases from third-party sellers on sites like Amazon. Sales taxes are generally regressive, though some progressive groups argue that taxing online sales doesn’t hurt poor families as much because people who shop online tend to have higher incomes.

- An increase in the gross production tax on oil companies drilling on public land. But the new 5 percent tax is still one the lowest among oil-producing states. (At least nine states have a similar tax, with Wyoming and Louisiana charging the highest rate: about 13 percent.)

Oklahoma had already been shifting the burden of public services onto the lower and middle classes.

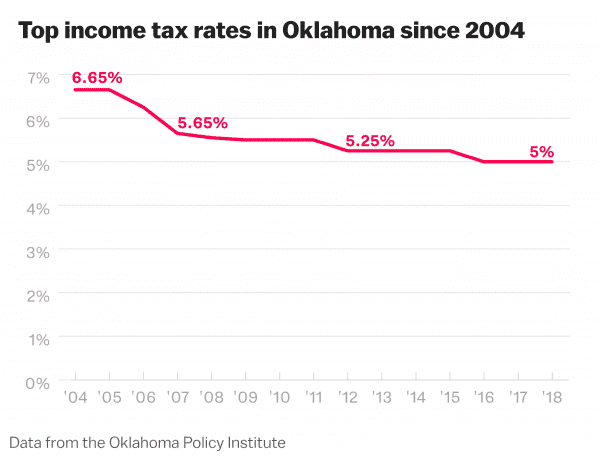

In the mid-2000s, the Oklahoma state legislature approved several tax cuts that largely helped the rich. “That was a time when the economy was booming and oil prices were high, and for a time it looked like you could have it all,” said David Blatt, who runs the Oklahoma Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

But when the economy tanked in 2008 and oil prices plummeted, the legislature just kept cutting taxes — which helped the wealthiest residents.

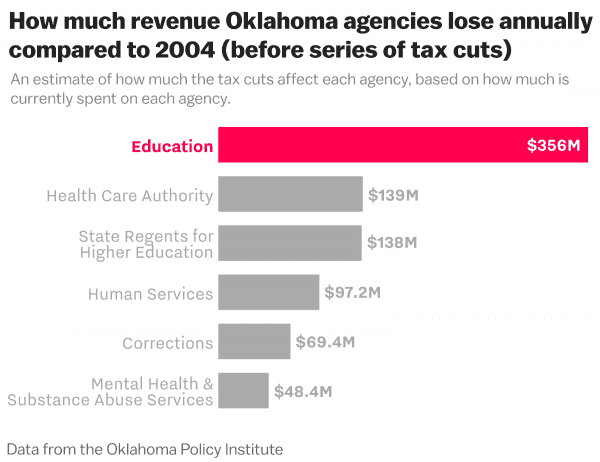

This spate of tax cuts hit education the hardest. The Oklahoma Policy Institute extrapolated how much these cuts cost education in the state each year and found that it’s more than $350 million annually.

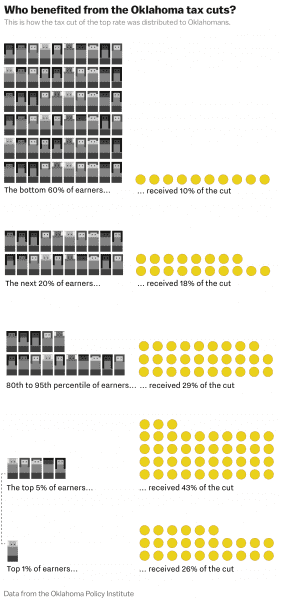

The top 5 percent of earners received about 43 percent of the cuts, and the top 1 percent received more than a quarter.

West Virginia

After a nearly two-week strike, West Virginia teachers and other state employees received a 5 percent pay raise as well as a hold on raising health insurance premiums.

But West Virginia didn’t pass any new revenue measures to pay for the raises. Instead, Senate President Mitch Carmichael bragged that they were able to do this “without increasing any taxes at all.”

Lawmakers say they’ll pay for the raises by not implementing planned spending increases on various projects, which include funding for economic development, tourism, and state building repair.

But there are some measures that will squarely hit lower-income residents. The state won’t have additional funding for a free tuition program for students in community and technical colleges. In addition, lawmakers said they will need to take money from the general services and Medicaid budgets. This means residents who rely on social services are losing out.

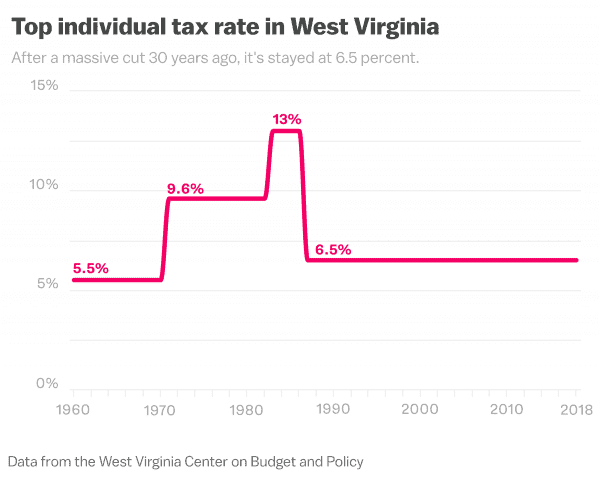

This stubborn refusal to raise taxes is part of a decades-long trend in West Virginia, which has been cutting taxes for decades. After the top individual tax rate climbed to 13 percent in the mid-1980s, the state cut it by half, and it’s stayed there ever since.

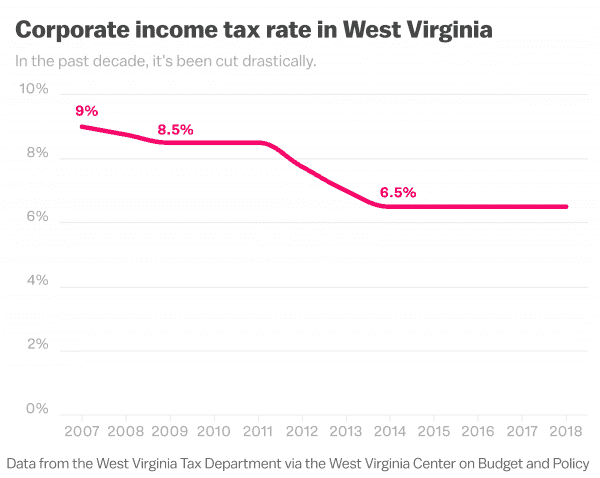

Meanwhile, in the past decade, the state has cut tax rates for corporations:

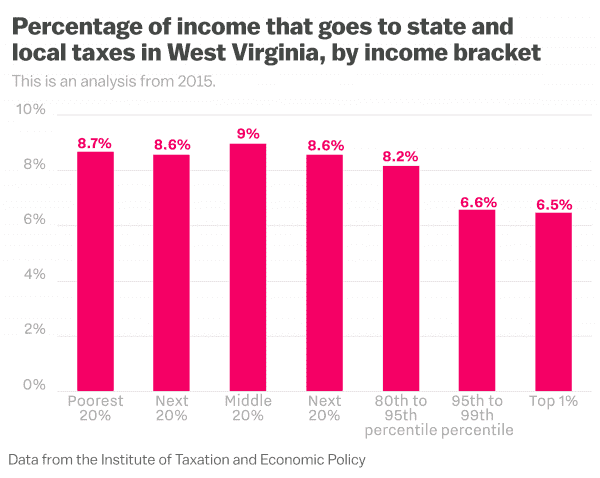

Put those two things together, and it means that wealthier West Virginians are paying a much smaller portion of their income to state and local taxes. Meanwhile, poor and middle-class residents shoulder a much larger load:

Kentucky

In Kentucky, teachers reluctantly backed a bill that boosted funding for education by raising taxes on everyone but the wealthy. (The alternative was an even more unappealing bill from Republican Gov. Matt Bevin.)

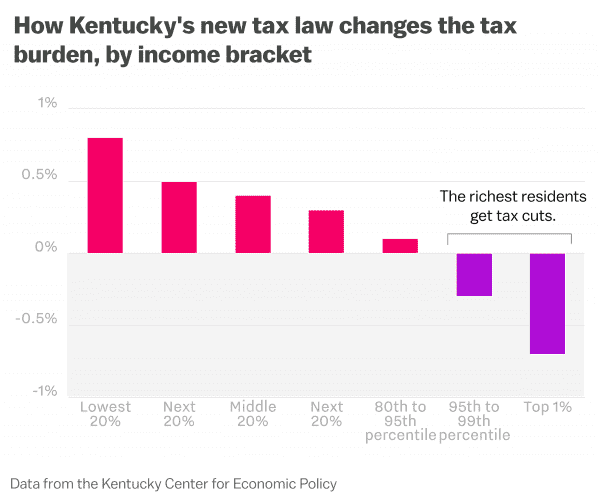

Bevin vetoed the bill, but he was overridden by lawmakers. The legislature increased funding for education but passed regressive changes to the Kentucky tax code to pay for it:

- There used to be six tax brackets for the individual income tax, with the top rate being 6 percent. That was changed to a flat 5 percent tax for everyone.

- The amount of pension income you can exclude from the state income tax decreased, which means people who rely on pensions (like teachers) pay more taxes.

- The corporate income tax used to have three brackets with a top rate of 6 percent, but that was also changed to a flat 5 percent for everyone.

- Sales tax now applies to several services that were once exempt, which hurts middle- and lower-income people more.

- The cigarette tax was raised from 60 cents to $1.10 a pack.

Ultimately, this means the top 5 percent of residents get a tax break; the bottom 95 percent will face tax increases, according to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy.

Sourse: vox.com