Magma swelled beneath the Mount Mayon volcano in the Philippines on Thursday and a column of ash more than a mile high spewed out, forcing 75,000 to flee. Officials are warning that a major eruption could happen any day now.

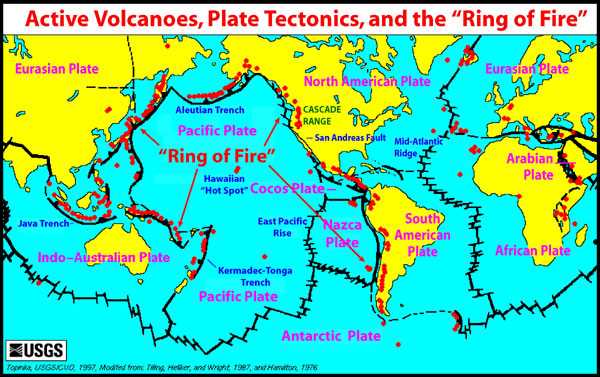

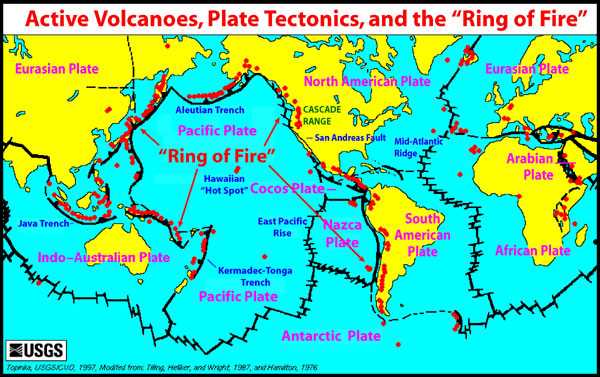

It’s the latest action in what’s already been a very rowdy week along the Ring of Fire, the geological region that follows the 25,000-mile perimeter of the Pacific Ocean and is home to 90 percent of the world’s earthquakes.

Mayon, the most active volcano in the Philippines, has erupted 50 times in the past 500 years; its current eruption, which has been slow so far, began on January 13.

Volcanologists are worried that larger eruptions may still be on the way — the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology updated its threat level to 4 this week, meaning that a hazardous eruption is imminent. Once a major eruption starts, the threat level will be raised to 5.

Tuesday also saw the eruption of Mount Kusatsu-Shirane, 100 miles northwest of Tokyo, which killed one soldier in an avalanche and injured a dozen at a ski resort. And further south, Indonesia’s Mount Agung, which has been spewing ash since November, had four distinct eruptions.

But wait — we haven’t even gotten to the earthquakes this week. A magnitude 4.0 quake jolted some Southern Californians awake early Thursday morning. And a magnitude 6.1 earthquake rumbled 100 miles southwest of Jakarta, Indonesia, on Tuesday, the same day a magnitude 7.9 earthquake struck off the coast of Alaska. (A tsunami warning was issued, and subsequently canceled, for the entire West Coast of the US.)

Could some of these events be related?

“The short answer is yes, earthquakes and volcanoes can interact,” said Emily Brodsky, a professor of earth and planetary sciences at the University of California Santa Cruz. But she noted it’s too early to connect the dots between all the activity we’ve seen this week, and it’s hard to say how much one event has influenced another.

Philippine researchers aren’t so sure — they’re saying the tremors and eruptions this week aren’t connected to one another because they happened so far apart.

Brodsky added that having multiple earthquakes and eruptions at the same time is not unusual, especially in a region that is so notoriously feisty.

However, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions are often clustered, she said. A volcanic eruption can cause tremors, while a large temblor can rattle a magma chamber underneath a volcano, causing towers of ash and rivers of lava to gush forth. The Puyehue-Cordón Caulle volcano in Chile erupted in 1960 just 38 hours after a magnitude 9.6 earthquake, for example.

This is because large tracts of the Earth’s crust called tectonic plates are constantly running into each other, sliding past each other, or rolling on top of each other. These movements can cause pressure to build up and dissipate in the form of earthquakes, or can create fissures that allow magma to reach the earth’s surface.

Scientists are starting to get a handle on how big geologic events influence each other, stitching together measurements of how an eruption in one part of the world can lead to tremors in another.

“One of the things that is helping us grapple is our vastly improved global instrumentation,” Brodsky said. Many countries, particularly in earthquake-prone regions, have been deploying networks of seismic sensors to gain a better understanding of movements of the ground.

The ultimate goal is to get ahead of these events so that the next time the ground shakes or a volcano growls, people won’t be caught off guard and lives can potentially be saved.

But that will require years of monitoring the earth with detailed measurements in some of the most remote places, like the bottom of the ocean, to build a baseline. It may be years before scientists can develop an early warning system.

For now, authorities in the Philippines are expanding the evacuation zone around Mayon to 5 miles, warning locals that a major eruption could be imminent.

Sourse: vox.com