“What is wrong with white women?” Moira Donegan asked at the Guardian after last week’s midterm elections.

“Why do half of them so consistently vote for Republicans, even as the Republican party morphs into a monstrously ugly organization that is increasingly indistinguishable from a hate group?”

Questions about white women’s allegiances came to the fore again this week, when news broke that a white woman senator facing a runoff in Mississippi had made a joke on the campaign trail about attending a “public hanging.”

Progressives sometimes expect white women, as a group, to support the interests of people of color of all genders — after all, women know what discrimination feels like.

“Most of us continue to see white women through the lens of gender,” explained Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, a history professor at UC Berkeley and the author of the forthcoming book They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South. “This allows for us to be optimistic about the possibility that their gendered oppression will allow for them to find common cause with other dispossessed groups.”

But that common cause has been elusive. There are some indications that white women across the country — especially those with college educations — are beginning to move away from Trump and his party. But 75 percent of white women voters cast their ballots for Republican Brian Kemp in Georgia’s gubernatorial election last week. In Texas, 60 percent of white women voted to reelect Republican Sen. Ted Cruz. And around the country, white women candidates used racist language and ideas in their campaigns, just as men did.

It’s a mistake to blame white women alone for Republican victories in 2018. After all, white men voted for Republicans in higher numbers nationwide. But to understand the appeal of a president who started his campaign by calling Mexican immigrants “rapists,” and a party that in many ways still follows in his footsteps, we have to understand the unique ways that racist ideology has appealed to white women across American history.

For centuries, Jones-Rogers said, white women have “invested in white supremacy because their whiteness affords them a particular kind of power that their gender does not.” If Democrats want to understand — and change — the political behavior of white women, they’ll need to understand how they’ve been both empowered and disempowered since the country was founded, and how that dual status affects their politics today.

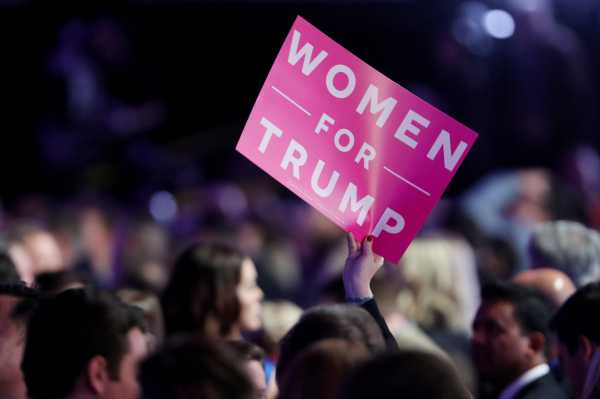

White women around the country voted for — and campaigned on — racist ideas

White women, as a whole, moved away from the Republican Party in 2018; 49 percent of white women voters cast their ballots for Republicans in House races, compared with 55 percent in 2016, according to CNN exit polls.

But looking at white women as a whole only gets you so far. It doesn’t explain the majorities who voted for Kemp, Cruz, or for Republican gubernatorial candidate Ron DeSantis in Florida, who told voters not to “monkey this up” by voting for his opponent Andrew Gillum, who is black.

It doesn’t explain candidates like Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith, who joked about a local rancher in Tupelo, Mississippi, earlier this month that, “if he invited me to a public hanging, I’d be on the front row.” As Phil McCausland notes at NBC News, Mississippi had more public lynchings than any other state in the period after the Civil War.

When criticized, Hyde-Smith, whose reelection bid goes to a runoff on November 27 and who has been endorsed by President Trump, acted like it was shocking that anyone was offended, saying in a statement, “I used an exaggerated expression of regard, and any attempt to turn this into a negative connotation is ridiculous.” A spokesperson for the Hyde-Smith campaign told Vox the senator had nothing to add to this statement.

When asked at a press conference on Monday if she was familiar with the history of lynching in Mississippi, Hyde-Smith said only, “I put out a statement yesterday, and that’s all I’m going to say about it.” Mississippi Gov. Phil Bryant then defended her by implying that critics should be angry, instead, about the “genocide of over 20 million African-American children” by abortion, a common anti-abortion talking point.

Other white women candidates, meanwhile, have used xenophobia in their campaigns. One ad for Rep. Marsha Blackburn, who won her Senate race in Tennessee, describes the caravan of migrants headed for the US border as containing “gang members, known criminals, people from the Middle East, possibly even terrorists.” The migrants in the caravan are from Central America, not the Middle East, and most are fleeing violence, poverty, or both, as Vox’s Dara Lind notes. Blackburn’s campaign ads mentioned the caravan almost 800 times, according to CNN.

Meanwhile, Rep. Martha McSally (R-AZ), who conceded defeat on Monday in her Senate race against Democrat Kyrsten Sinema, said in March that California “sanctuary cities” were endangering Arizona. “If these dangerous policies continue out of California, we might need to build a wall between California and Arizona as well to keep these dangerous criminals out of our state,” she said.

In the 2018 election, then, white women were both producers and consumers of racist ideas. And while white women may have a number of reasons to vote Republican, it’s impossible to ignore the impact of racism on their behavior as a group.

The politics of racism has always worked on white women

White women’s willingness to support candidates who embrace racism is far from a new phenomenon, Jones-Rogers said. White women’s “investments in white supremacy have shaped their experiences from the moment of settlement, and it is that longer history that we need to consider as we are trying to understand their voting patterns and their racist behavior now.”

Before emancipation, Jones-Rogers said, slave-owning parents systematically trained their daughters to become slave-owners themselves. Parents “would give enslaved people to their daughters when they were only girls, sometimes even when they were only infants, and they routinely informed their daughters that those enslaved people belonged to them,” she explained. White girls and women “were expected to keep enslaved people in submission, to buy and sell them when necessary, and to play significant roles in upholding the institution of slavery.”

The attitudes forged under slavery didn’t disappear with emancipation. During Reconstruction, white women were responsible for countless lynchings around the country when they falsely accused black men of sexual assault, Jones-Rogers said. Some photographs of lynchings “show white girls standing and smiling near black men’s dangling corpses.”

“Sen. Cindy Hyde-Smith was drawing on a much longer history which directly ties white girls and women to public hangings,” she added.

Meanwhile, politicians have used race and racism to appeal to white women throughout American history, said Ibram X. Kendi, a history professor at American University and the author of Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America.

In recent decades, the war on crime has been pitched as an effort to keep white women safe, Kendi said. White women have been the plaintiffs in some lawsuits against affirmative action, and conservatives have argued that the practice harms white women, even though research has shown that white women have been some of the greatest beneficiaries of affirmative action.

Most recently, supporters of the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh directed their comments specifically at white women, Kendi said. “The defense was: What if this happened to your husband or your son or your brother — which was a direct appeal to white women.”

Race-based appeals to white women are similar, in some ways, to appeals to poor white voters of all genders. In both cases, politicians like Trump set up people of color as “this enemy of white people” and then present themselves as “the savior from that very enemy.”

“That is how a billionaire who is extremely sexist can simultaneously attract poor whites who imagine him as their defender, and white women who imagine him as their defender,” Kendi said.

White women who vote for racist candidates are endorsing not just racism, but also sexism, he explained. They’re buying into the racist idea that their privileges as white people “are withering away” as well as “the sexist idea that imagines that all white people are men or that the white race is masculine.” That sexism allows white women to feel that by defending white men, “they’re defending themselves.”

White men’s interests aren’t always white women’s interests, especially when those white men are part of a Republican Party that fails to take sexual harassment and assault seriously and campaigns on overturning Roe v. Wade, something even a majority of Republican voters oppose. Racist politics won’t work as well on white women if those women “see what white men are gaining and what they are simultaneously losing from racism and sexism,” Kendi said.

But at the same time, white women have had something to gain, historically, from racism. Public lynchings, Jones-Rogers said, “taught white girls and women that, for all the legal constraints they faced in most aspects of their lives, their accusations of rape or improper behavior, which they lodged against African-American men, women, and children, would be taken seriously.” We can see the repercussions of those lessons in the white women who call police on black people and other people of color today, when those people are engaged in no criminal behavior, she added.

“When we acknowledge that white girls and women were able to exercise power in this nation, from its colonial beginnings, because of their whiteness,” she said, “it becomes easier to understand why white women vested in white supremacy and white supremacist activities and movements long after slavery.”

And it becomes easier to understand why some white women today might feel an allegiance to the Republican Party not in spite of, but because of, the racism of white men like Trump.

Sourse: vox.com