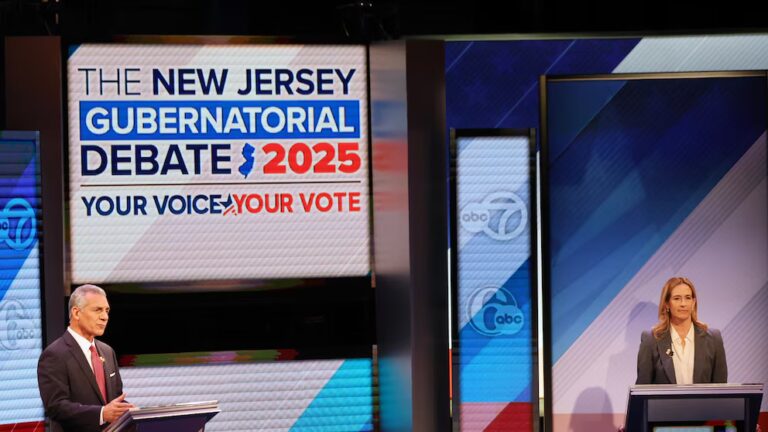

On November 17, 2016, a bat flew into Ally McNamee’s mouth.

At the time, McNamee was a student at Keene State College in New Hampshire. A bat flew into her house, and she attempted to shoo it away with a broom, assuming the bat would retreat. It did not.

“It flew at my face, and I screamed,” McNamee says. “My mouth was open. I definitely caught a wing.”

When she woke up the next day, she started to worry about rabies. She went to the local urgent care center, which sent her to the emergency room. It was the only facility that stocked the drugs necessary to treat rabies, a situation that is typical across the United States.

A few weeks later, the bill arrived: $6,017. The vast majority of the charge was for a drug to treat rabies exposure called immunoglobulin. The emergency room billed this drug at $3,706.

And it turns out McNamee’s bill was actually at the low end of what hospitals charge for the drug in the United States, which can sometimes be closer to $10,000.

Vox learned of McNamee’s bat incident during a running, months-long investigation into emergency room costs. Readers from across the country have contributed more than 1,000 bills to Vox’s emergency room bill database. In reviewing those bills, I kept coming across something I didn’t expect to see: readers with significant medical debt from rabies treatment.

Michael Cinkosky also sent me a bill from a visit to a hospital near Denver. A bat collided with his 8-year-old son’s chest last summer and left behind two scratch marks, a sign of a possible bite. That hospital billed the same rabies drug at $10,494.

The Cinkosky family was responsible for $3,563 of the hospital bill, which they’re still paying off.

“Rabies is 100 percent fatal. What are you going to do? Not get it?” Cinkosky says. “We’ve been living off our reserves because of the bills, and that’s not a good long-term strategy.”

In England, the drug to treat rabies exposure costs $1,600. Here, hospitals charge $10,000.

The price of rabies treatment in American reveals unique failures of our country’s health care system. It shows that in the United States, pharmaceutical companies can set sky-high prices for lifesaving medication.

Specifically, the drug that prevents rabies from spreading to the brain can cost more than $10,000 in the United States. In some cases I reviewed, hospitals charged more than six times what the identical drug would cost in the UK.

Insurance plans will often negotiate down those charges, but even those lower prices are still multiples higher than what patients pay in our peer countries, such as Canada or England.

“Rabies treatment is more expensive in the United States, as are many medical treatments, because we don’t have price controls,” says Charles Rupprecht, a biomedical consultant who previously ran the rabies control program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emergency rooms, meanwhile, can exacerbate the pricing problem.

ERs typically are the only locations where patients can find the lifesaving treatment. And they charge significant “facility fees” to anyone who walks through their doors to seek treatment — including patients seeking a rabies vaccine.

Because rabies treatments includes a series of four shots delivered over two weeks — all at separate appointments — those costs can add up quickly.

“I have to go to the ER to get the drug, and each time I walk in the door, that is a $250 copayment just to start,” says Lisa Peterson, who went through rabies treatment in Utah in 2016 after being bitten by a raccoon. The public health department told her the only place she could get the injection was at the local emergency department.

She is still paying off her bills for the treatment — about $4,500 in total — with $100 a month. She still has about $600 to go, from emergency room visits that happened in the fall of 2016.

“When I got the bill, I called them crying,” she says. “I can’t pay this. Each time, the doctor comes in for a minute, looks at the bite, and gives me a shot. How do they feel comfortable billing me so much?”

Help our reporting

Hospitals keep ER fees secret. Share your bill here to help change that.

Depending on where you go, a key rabies drug could cost $280 — or $9,912

Between 20,000 and 40,000 Americans are treated each year for rabies exposure, typically after encounters with wildlife including bats, raccoons, and skunks.

The first step in treatment involves two drugs: a rabies vaccine and something called rabies immunoglobulin. The immunoglobulin essentially kicks the immune system into overdrive, staving off the rabies virus until the vaccine begins to take effect.

“The immunoglobulin is what intervenes before the illness can go from the periphery of the body into the central nervous system, and eventually into the brain,” Rupprecht explains. “That buys you time.”

Rabies immunoglobulin costs more than something like a flu shot because it’s derived from human blood, which has to be carefully screened for disease. The cost means the drug is often unavailable in developing countries.

But the prices in the United States are still exceptionally high. Derek Evans, a British pharmacist who is the chair-elect of the International Society of Travel Medicine professional group, helped me look up the price of rabies immunoglobulin in the United Kingdom.

The British National Formulary shows that in the UK, one vial of rabies immunoglobulin costs £600, or $813. Evans says the average male would require two vials (the drug is dosed based on weight) bringing the total price to £1,200, or $1,626 — a fraction of the costs I’ve seen on American hospital bills. The British government also covers all the costs for rabies exposure treatment, leaving patients there with no bill.

“It’s a long way off from $14,000, isn’t it?” Evans remarked when I told him about the charges I’d seen here in the United States.

Finding out the price of this rabies treatment in advance can prove vexing, if not impossible. The CDC estimates that it costs between $3,000 and $7,000.

The health data firm Amino combed through 45,000 claims for rabies treatment and found about half of the bills ranged from $280 to $4,500. Five percent of the bills were above $9,912, suggesting that emergency rooms and possibly drug manufacturers have wide leeway on what they charge for the exact same medications.

The Amino data represents the actual price paid for the rabies vaccine by patients and insurers, and not the hospital charges.

“If this were a flu shot, the variation in prices would be really narrow,” says Sohan Murthy, chief data scientist at Amino. But he says this kind of price variation is typical when you move into the emergency room setting, where patients often have little idea what their treatment will cost until the bill arrives.

“High variation in prices for emergency room-type things is something we see a lot of in different types of medical encounters,” Murthy says.

The Swedish Medical Center near Denver — the hospital that saw Benjamin Cinkosky, the 8-year-old boy who was struck by a bat — did not respond to multiple requests for comment on how it set its prices.

Sanofi, which manufacturers one of the two brands of rabies immunogloublin provided Vox with a statement regarding its prices: “Rabies is a serious viral infection that is nearly always fatal. We believe the price of the immunoglobulin is appropriate taking into consideration the life-saving value the product may provide and the complexity of its manufacturing.”

Pricey “facility fees” drive the costs of rabies treatment even higher

Most health care providers do not stock rabies immunoglobulin because the expensive drug has a short shelf life, typically expiring a few years after production. There’s a decent chance the drug would expire on a primary care doctor’s shelf.

Emergency rooms, however, do keep this lifesaving medication in stock. The Amino data set shows that 95 percent of post-exposure rabies treatment happens in ERs.

Emergency rooms typically tack on hundreds or thousands of dollars in hospital and doctor fees just for receiving the injections in an ER setting. “Facility fees” are the price emergency rooms charge for walking in the door and seeking care. These fees have risen steeply in recent years: up 89 percent over just six years, according to my recent investigation with the Health Care Cost Institute.

The fees also vary significantly from hospital to hospital — and even within the same hospital.

Lisa Peterson learned this firsthand after a raccoon bit her in October 2016. She called the public health department, which told her the only place she could seek treatment was her local emergency room.

St. Mark’s Hospital in Salt Lake City billed Peterson $14,444 for her first visit. She was ultimately responsible for $941.

What jumped out at Peterson was that her emergency room would charge different prices for her follow-up visits. To her, the visits all seemed the same: a quick stop by the emergency room to receive a shot of the rabies vaccine.

But sometimes her visits were billed with a “level 1” facility fee, the cheapest fee for the simplest visits. But another visit was coded as “level 2,” which came with a higher price. And still another was “level 4,” typically reserved for some of the most complex visits.

“Every time, the fee was different,” Peterson says.

In addition to her $250 emergency room copayment, these fees got tacked onto her bill. Peterson was charged a $105 facility fee when her visit was coded as level 1, but a $679 facility fee when the hospital coded a visit as level 4.

Peterson’s share of the bill ranged from $51 up to $230 depending on which code the hospital used.

St. Marks Hospital in Salt Lake City, where Peterson was treated, did not respond to a request for comment about how it set the prices for Peterson’s care.

Peterson says it was frustrating that she couldn’t get her care — or at least the follow-up shots, which don’t expire quickly like the immunoglobulin — at a public health department, where she wouldn’t need to pay facility fees. But the department has told her repeatedly that it doesn’t stock the medication or have plans to do so.

Like many Americans, Peterson factors in price when making decisions about health care. She has not seen a doctor about pain she has in her shoulder because she doesn’t think she has the money right now to pay for treatment.

But with rabies treatment, it was different: She was dealing with possible exposure to a disease that is always fatal. She needed to seek treatment — and she didn’t have a choice about where to do so, essentially requiring her to pay whatever prices the emergency room wanted to charge.

“I get it for the first shot, going to be seen by the emergency room,” she says. “But the next three? I don’t get it. It seemed absolutely backward that the only way to get treated with rabies is through the emergency room. That is crazy to me.”

Help us report on the costs to visit the emergency room. Share your bill here.

Sourse: vox.com