Once it became clear Marvel’s Black Panther would be a huge draw to movie theaters, a trio of black women had an idea: If black communities would turn out in large numbers to see the film, why not seize the opportunity to get people registered to vote?

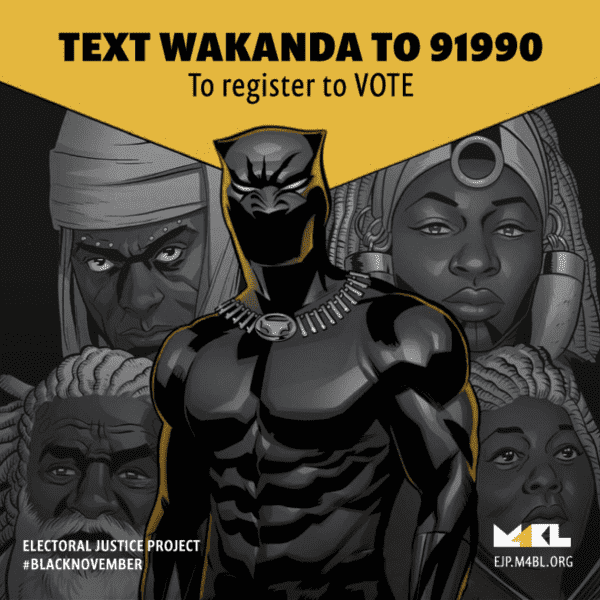

The result was the #WakandaTheVote campaign, an initiative that allows people to set up voter registration events at local theaters or register to vote via text message. The initiative is headed by Kayla Reed, Jessica Byrd, and Rukia Lumumba, who also created the Movement for Black Lives’ Electoral Justice Project. The EJP aims to “continue a long legacy of social movements fighting for the advancement of the rights of Black folks through electoral strategy.”

It turns out that using Black Panther’s record-setting opening is one way to accomplish those goals. “In watching Black Panther, what feels familiar about the real world that we’re in and Wakanda is that we need someone to defend our communities against attack,” Reed, a St. Louis-based organizer, told Vox on Tuesday. “We need to step into the idea that we can all be superheroes and we can all be change agents in our communities.”

#WakandaTheVote, much like the varying campaigns of the broader Movement for Black Lives, is a largely crowdsourced effort, relying on local communities to create and run their own registration events.

The campaign has already seen considerable support: some 20 registration events took place over the weekend in cities like Dallas, Durham, Miami, and Atlanta, and people have signed up to hold more than 100 registration events in at least 50 cities since the initiative launched, suggesting that the campaign could expand considerably in the next few weeks.

The campaign also enables people to register to vote using their phones by texting a prompt that then directs them to a registration website.

Reed says more than 1,000 people have registered to vote using this method so far. (Since the campaign relies on survey responses to determine how many people were registered at any given theater, it will take some time before an estimate of those numbers is available.)

#WakandaTheVote is part of a broader effort to change how black communities engage with politics

Reducing barriers to the political process is a core goal of the EJP. When the project began last year, Reed says the focus was not only on coordinating local and national election initiatives for the Movement for Black Lives’ member groups, but also on educating black communities about the impacts of political issues and how the electoral process can serve as a means of effecting change.

When the EJP started in October, it hosted community-based events and town halls that allowed it to interact directly with community members and understand how local communities view electoral politics. Those interactions had a direct influence on the #WakandaTheVote effort.

Communities of color are deeply concerned about political issues, especially under the Trump administration, Reed says, but black communities “haven’t been sold on the fact that voting changes the issues that their communities are facing.” She added that black communities are often persuaded to vote for politicians who later ignore their needs. She argues that the registration campaign is a way to encourage people to see those connections by giving community groups the tools to empower one another.

Reed says another important point of the EJP and the current voter registration effort is its timing. Rather than waiting for the early fall to start a voter registration campaign for the 2018 midterm contests in November, Reed explains that the registration campaign is designed to engage with voters much earlier in the process. Instead of simply adding names to the voter rolls, the campaign is more about encouraging black people to participate in elections than persuading them to support a particular candidate or party.

That’s how the project is attempting to set itself apart from candidate-driven efforts or groups like the Democratic National Committee, which has been criticized by black organizers and political strategists for assuming that black voters will support certain candidates and limiting black outreach efforts to late in the election cycle.

“Coming in late is exploitative because there’s an ask without any type of investment,” Reed says. “There’s no promise that policing is going to get better if we vote for the Democrat; there’s no promise that economic justice will be on the platform if we vote for the Democrat.” Instead, she says, it’s important for groups to build credibility in communities over time.

It’s a change that other black organizing groups have sought, working in recent elections in Virginia and Alabama to turn old models of engaging with black voters on their head by emphasizing the ballot as a way for black communities to show their power and encouraging long-term voter persuasion efforts.

The EJP says that the next few weeks of the #WakandaTheVote campaign are just the beginning; a similar registration campaign centered on Ava DuVernay’s A Wrinkle in Time is currently in the works. The Electoral Justice Project is also looking to launch several new projects in upcoming months, including an initiative that will train black organizers to work on electoral issues, and an information project that will serve as a resource for grassroots black political efforts moving forward.

The organizers say the current voter registration effort crystallizes what the Black Panther film represents: the strength of black communities and the political and cultural power of art. “Black art has always been political,” Reed says. “I’m just really grateful that people saw what #WakandaTheVote could mean to the ability for black people to self-determine [our futures] and really govern ourselves and our communities.”

Sourse: vox.com