While congressional and gubernatorial races got much of the attention during Tuesday night’s 2018 primary elections, there were some very big victories in local races for anyone who cares about ending mass incarceration.

According to Matt Ferner at HuffPost, two progressive prosecutor candidates running for district attorney won their primary elections in North Carolina — putting them in a crucial spot to determine how the criminal justice system works.

In Durham County, Satana Deberry, a former criminal defense attorney, won her Democratic primary on a platform promising to oppose cash bail, hold police accountable, and resist the war on drugs — all key progressive demands for the criminal justice system. Since she’s so far not facing another challenger in November, her primary victory means she should become the next district attorney for Durham County, barring a write-in campaign.

Meanwhile, in Pitt County, Faris Dixon, who’s currently a defense attorney, won in the Democratic primary as well. According to Ferner, “Dixon supports the formation of a conviction integrity unit to review closed cases and ensure that defendants were not wrongfully convicted, expanding the use of drug courts in the region and creating more transparency out of the DA office” — again, major progressive planks. But he’s facing a Republican candidate in November, so his position isn’t a sure bet yet.

These may seem like minor local elections, but they are exactly the kinds of races that need to happen to significantly change the criminal justice system. These prosecutor offices are perhaps the most powerful in the criminal justice systems — helping decide who goes to prison, for what, and for how long. And since the great majority of people in jail and prison are held at the local and state level, district attorneys (who enforce state laws) have the biggest role where the bulk of criminal justice action happens in America.

In the past, these races haven’t gotten too much attention. A previous study by Ronald Wright of Wake Forest University School of Law, looking at data for 10 states, found that about 95 percent of incumbent prosecutors — often supporters of old “tough on crime” and war on drugs–focused policies — won reelection when they sought it between 1996 and 2006. This helped perpetuate the status quo of mass incarceration.

Now criminal justice reformers, backed by major funders like George Soros, are pouring time and money into prosecutor races to reshape the criminal justice system. They have already had major victories — including that of Larry Krasner in Philadelphia, whose staff, among several other reforms, declines to prosecute any marijuana possession case. With more victories, these reformers could seriously reshape how the criminal justice system works.

Prosecutors are key drivers of mass incarceration

Typically, discussions of the criminal justice system focus on lawmakers, prisons, the police, and maybe judges. Rarely, however, is the most powerful actor in this system mentioned: the prosecutor.

Prosecutors are enormously powerful in the US criminal justice system, in large part because they are given so much discretion to prosecute however they see fit. For example, former Brooklyn District Attorney Kenneth Thompson in 2014 announced that he would no longer enforce low-level marijuana arrests. Think about how this works: Pot is still illegal in New York state, but Brooklyn’s district attorney flat-out said that he would ignore an aspect of the law — and it’s completely within his discretion to do so.

Prosecutors make these types of decisions all the time: Should they bring the type of charge that will trigger a lengthy mandatory minimum sentence? Should they bring a charge that’s only a misdemeanor? Should they strike a deal for a lower sentence, but one that can be imposed without a costly trial?

Courts and juries do, in theory, act as checks on prosecutors. But in practice, they don’t: More than 90 percent of criminal convictions are resolved through a plea agreement, so by and large, prosecutors and defendants — not judges and juries — have almost all the say in the great majority of cases that result in incarceration or some other punishment.

John Pfaff, a criminal justice expert at Fordham University, has found evidence that prosecutors have been the key drivers of mass incarceration in the past couple of decades. Analyzing data from state judiciaries, he compared the number of crimes, arrests, and prosecutions from 1994 to 2008. He found that reported violent and property crime fell, and arrests for almost all crimes also fell. But one thing went up: the number of felony cases filed in court.

Prosecutors were filing more charges even as crime and arrests dropped, throwing more people into the prison system. Prosecutors were driving mass incarceration.

Pfaff provided a real-world example of this kind of dynamic in his book Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform: “Take South Dakota, which in 2013 passed a reform bill that aimed to reduce prison populations. The law did lead to prison declines in 2014 and 2015, yet at the same time prosecutors responded by charging more people with generally low-level felonies, and over these two years total felony convictions rose by 25 percent.” In the long term, this could lead to even larger prison populations.

Now apply this story on a national scale. There is less crime compared to the 1990s. Police are making fewer arrests. Lawmakers are slowly reducing the length of prison sentences. Yet until 2010, incarceration rates had continued to climb nationwide — and, as Pfaff pointed out, the recent drop in incarceration would be much less pronounced if it wasn’t for court-ordered drops in California’s prison population. Prosecutors have been abetting more and more incarceration while other actors in the system have been pulling back.

By successfully campaigning for progressive prosecutors, criminal justice reformers stand to change this dynamic. It’s crucial this happens at the local and state level too, where the majority of the criminal justice system takes shape in the US.

In criminal justice, it’s local and state systems that matter

Local races don’t typically get much national attention, especially with so much going on at the federal level. But it’s exactly because these races are local that they should matter a lot for anyone who’s interested in reversing mass incarceration.

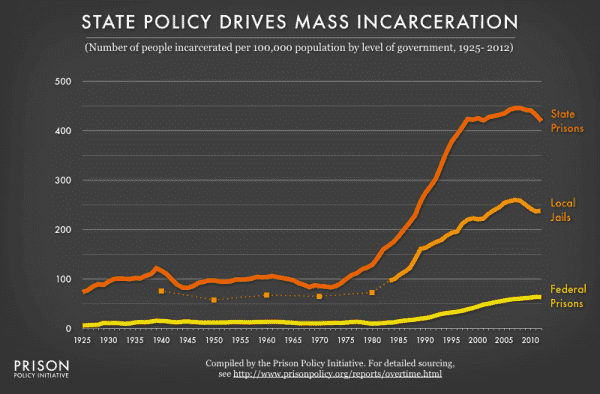

Consider the statistics: According to the US Bureau of Justice Statistics, 87 percent of US prison inmates are held in state facilities (and most state inmates are in for violent, not drug, crimes). That doesn’t even account for local jails, where hundreds of thousands of people are held on a typical day in America. Just look at this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative, which shows both local jails and state prisons far outpacing the number of people incarcerated in federal prisons:

One way to think about this is what would happen if President Donald Trump used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 593 per 100,000 people, only the small nation of El Salvador would come out ahead — and America would still dwarf the incarceration rates of other developed nations like Canada (114 per 100,000), Germany (78 per 100,000), and Japan (45 per 100,000).

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America, only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall almost wholly to municipalities and states. That’s why Deberry’s and Dixon’s victories are such a big deal: They show major changes happening exactly where criminal justice reform can have the most effect.

For more on mass incarceration, read Vox’s explainer.

Sourse: vox.com