Hawaii’s ballistic missile scare struck fear into the state’s roughly 1.4 million residents earlier this month, including, as it turns out, the employee who accidentally sent it. A report from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released Tuesday on the brief January 13 panic revealed that the person who pushed the button to send the alert believed there was an actual emergency and a missile was incoming. Hawaiian officials said on Tuesday that the employee has been terminated — and has a history of confusing drills and real-world events.

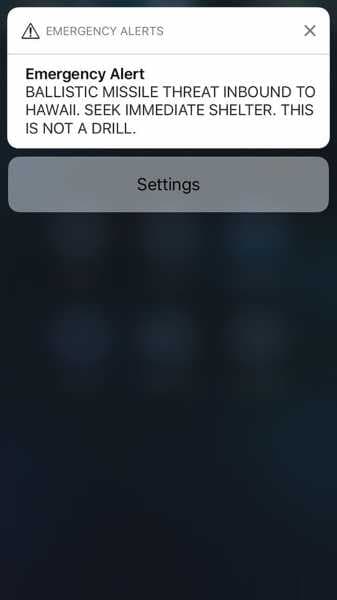

The FCC faulted the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s procedures for the 38-minute false alarm that caused widespread panic when an alert was sent to hundreds of thousands of phones and flashed on televisions in Hawaii that read: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Hawaiian officials had previously blamed the snafu on an employee who pushed the “wrong button.” But the FCC’s report reveals that the individual who pushed that button didn’t think it was the wrong move at the time and instead believed a practice emergency drill was, in fact, the real thing. The employee who transmitted the alert said in a written statement that he or she believed a missile was actually inbound.

At a press conference later in the day on Tuesday, Hawaiian officials released a separate report on the incident and confirmed that the employee has been terminated. The report said the worker who pushed the button, referred to as “Employee 1,” had been a “source of concern” at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency’s “state warning point” for more than a decade and was “unable to comprehend the situation at hand and has confused real life events and drills on at least two separate occasions.” Another employee resigned before disciplinary action could be taken, and another has been suspended without pay.

“We have identified and implemented the changes required to assure that what happened on January 13 will never, ever be repeated again,” Hawaii Gov. David Ige said at a Tuesday press conference.

The FCC announced the same day as the January 13 false alarm that it would launch a full inquiry. FCC Chair Ajit Pai in a statement accompanying Tuesday’s preliminary report said the investigation has, thus far, found that Hawaii’s emergency management agency didn’t have “reasonable safeguards” in place to prevent human error from resulting in a false alarm, and that it didn’t have a plan for what to do if a false alert was transmitted.

This could be why, after the mistaken alert at 8:07 am Pacific time, a second alert stating there was no emergency didn’t come out until 38 minutes later. It took Hawaii Gov. David Ige 17 minutes to inform constituents there was no missile threat because he didn’t know his Twitter password. (He has since learned it.) Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D-HI) beat both Hawaii’s emergency agency and its governor to the punch.

Even with all the explanations, this is still pretty unnerving

The alert has raised questions about emergency alert system processes and nuclear preparedness across the country. How could something like that happen because of a single human error, especially in light of tensions between the United States and North Korea and global nuclear proliferation?

“Everything is on hair trigger, so any possible mistake is very unsettling, to say the least,” Irwin Redlener, director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University, told me earlier this month. “It reminds us how precarious the nuclear age is on so many levels, and it’s really unsettling.”

Hawaiian officials told the New York Times soon after the incident that a new procedure has been implemented requiring two people to sign off before an alert like Saturday’s is sent, and the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency released a timeline of events surrounding the alert. The FCC on Tuesday also announced new rules to improve the geographic targeting of wireless emergency alerts, requiring providers to deliver alerts in a more “geographically precise manner” and ensuring such alerts remain on phones for 24 hours after receipt.

“Every state and local government that originates alerts needs to learn from these mistakes. Each should ensure that it has adequate safeguards in place to prevent the transmission of false alerts, and each should have a plan in place for how to immediately correct a false alert,” Chair Pai said in a statement.

“The public needs to be able to trust that when the government issues an emergency alert, it is indeed a credible alert. Otherwise, people won’t take alerts seriously and respond appropriately when a real emergency strikes and lives are on the line.”

Update: Story updated with employee’s termination and Hawaiian officials’ report on the missile scare.

Sourse: vox.com