A federal judge ruled Saturday that the Trump administration must stop plans to halt in-person census counting early — at least temporarily.

The long-term fight over the administration’s efforts to shorten the census data collection period will continue under the decision, which resulted in a temporary restraining order from US District Judge Lucy Koh of the Northern District of California. Koh’s order requires the administration to stop scaling back counting efforts until at least September 17, when another court hearing will help determine when counting will end.

The potential consequences are vast: The census count influences not only the number of representatives each state gets in Congress, but how much federal funding each state receives — and how voting district lines are drawn for the next decade.

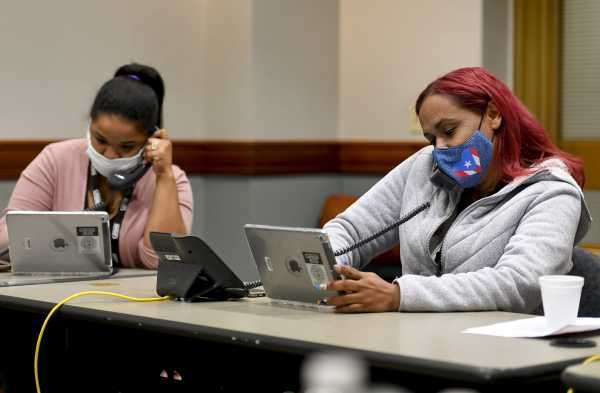

Ahead of the coronavirus pandemic, census data collection was scheduled to conclude on August 15; however, it was extended until October 31 given the challenges the pandemic created, particularly around in-person outreach — a key way of ensuring hard-to-count populations are included in the final tally.

In early August, the bureau announced it would end counting at the end of September instead, arguing doing so was necessary to meet the December 31 deadline to send the final numbers to Congress. Work to wind down counting is already underway, according to the associate director of the census, who said in court filings that the agency had already started firing temporary employees in some areas.

A number of civil rights groups, local governments, and the Navajo Nation — among others — sued over the new deadline, and Koh determined communities would likely experience irreparable harm if the census count was cut short.

“An inaccurate count would not be remedied for another decade,” Koh wrote. That “would affect the distribution of federal and state funding, the deployment of services, and the allocation of local resources for a decade.”

The consequences of an undercount would hit low-income and minority communities the hardest

If the census count is ended sooner than planned, it could bring lasting consequences.

As of now, around 35 percent of households haven’t responded to the census. But the impact of that isn’t shared equally.

Large swaths of the country lag behind the 2010 response rate, according to a research initiative led by the Center for Urban Research at the CUNY Graduate Center. Rural areas in Montana, Texas, Oregon, New York and elsewhere remain more than 10 percentage points behind their response rate a decade ago. Renters, low-income people, young children, and immigrants are among those who are the hardest to count.

Overall, about 20 percent of homes were counted through a “followup,” which involves Census Bureau employees visiting homes in person or counting families using other records.

But Rob Santos, vice president and chief methodologist at the Urban Institute and president-elect of the American Statistical Association, told Vox’s Nicole Narea that method relies in part on reports from neighbors, which aren’t as accurate, and on Social Security and IRS data. The federal government is less likely to have reliable administrative data on hard-to-count households than others. For example, unauthorized immigrants who do not have Social Security numbers may be less likely to file taxes with the IRS.

These complications mean ending the census count early could leave immigrant and rural communities, as well as communities of color, without the financial, educational, and political resources their true populations would state they are due. Latino advocates in particular have been particularly vocal in raising the alarm about how an undercount could undercut the political power of Latino voters.

But it’s not just civil rights advocates who are concerned. Four former census directors have asked the Trump administration to push the deadline to respond to the census even further out, until April 2021.

Trump is no stranger to politicizing the census. He sought to include a question on citizenship status in the 2020 census; several states challenged it in court, arguing it would depress response rates. The Supreme Court ruled in their favor in 2019 because the administration had lied about why it had pushed to include the question.

Instead of fighting that ruling, Trump issued an executive order that required the Census Bureau to use administrative records to create estimates on citizenship, and allowed the agency to collect more data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Customs and Border Protection, and Citizenship and Immigration Services.

In July, it became clear why the administration hoped to get that data. Trump issued a memo excluding unauthorized immigrants from being included in the counts for congressional districts in 2021. That, too, has been challenged in court.

More will become clear about the schedule for ending the census on September 17. But for now — with money and power on the line — the count will continue.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work, and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Sourse: vox.com