The momentum was with Medicaid this week: Nebraska is very close (pending a court decision) to putting Medicaid expansion on the ballot in November, and Maine’s highest court ruled that the state should finally expand Medicaid, as the citizenry voted to do last year.

And a new report out of Ohio, documenting the first five years of expanded Medicaid in the Buckeye State, gave us a clear picture of the stakes in these debates. The Ohio report is a rigorously collected and extensive data set on what happens in a state when it expands Medicaid with no frills (i.e., without a work requirement) and lets the program work its will for a few years.

As is our preference here at Vox, we can walk through the findings with the help of some handy charts.

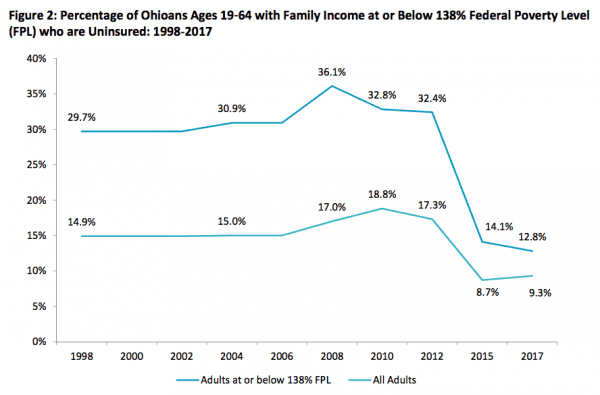

The dramatic slope of the uninsured rate tells the story. For the people eligible for expanded Medicaid — 138 percent of the federal poverty level, or $21,000 for a family of three, and below — the uninsured fell by more than half, from 32.4 percent before Medicaid expansion to 12.8 percent.

Medicaid expansion covers people in a population where the rate of uninsurance is exponentially higher than it is for people who make more money. That much is clear. Before Obamacare, one in three people in or near poverty were uninsured in Ohio. After Obamacare, that’s dropped to one in eight.

A few secondary findings stick out:

- There is a lot of churn: Less than 40 percent of people who initially enrolled in Medicaid expansion have been continuously covered.

- People who left Medicaid expansion did so because their income increased/they got a job, or they obtained non-Medicaid coverage, in almost every case.

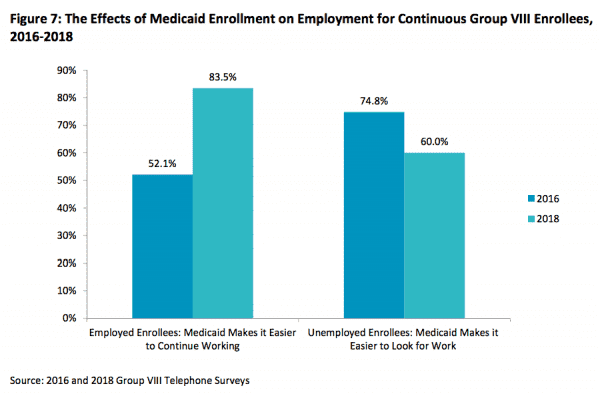

- About half of Medicaid expansion enrollees work, and the vast majority of them (84 percent) said having Medicaid made it easier to work — a notable stat as Ohio considers adding a work requirement to Medicaid.

- Those who are unemployed also largely said Medicaid made it easier for them to look for work, though there was a curious drop in the share who said so from 2016 to 2018.

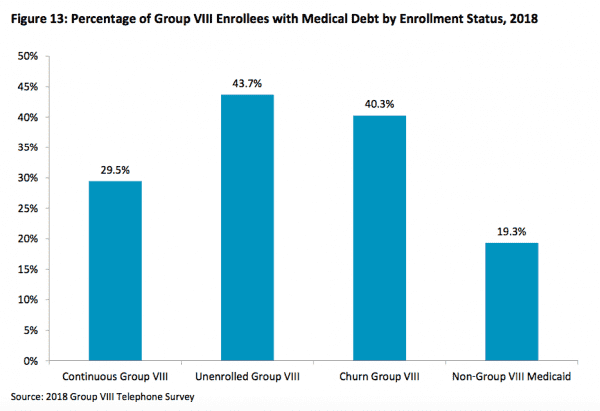

Another key finding: People continuously covered by Medicaid were substantially less likely to have medical debt than eligible people who were still uninsured or people who churned on and off of Medicaid.

That aligns with prior studies published in Health Affairs and elsewhere. If the purpose of Medicaid is to provide people with health care and a certain level of basic economic security, it seems to be succeeding.

Ohio is one of the states hardest hit by the opioid crisis — more than 4,000 Ohioans died of opioid overdoses in 2016 — and Gov. John Kasich, a Republican, has defended Medicaid expansion in part because of how it helps poorer residents struggling with opioid addiction access treatment.

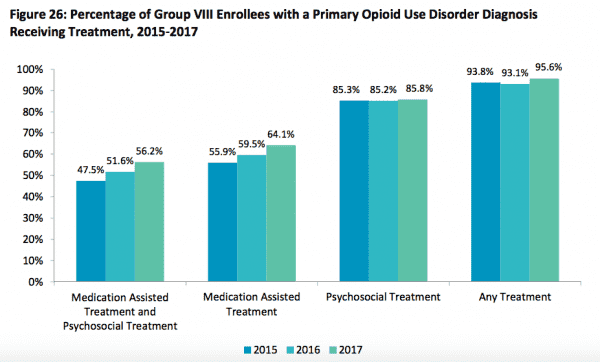

The numbers bear that out: Rates of Medicaid expansion enrollees with opioid use disorders receiving medication-assisted treatment and mental health counseling in tandem have risen steadily over the past few years.

We can hope that puts to rest any misguided notions that Medicaid expansion might have worsened the opioid epidemic — a claim that has been debunked (including by Emma Sandoe and Andrew Goodman-Bacon in Health Affairs) time and again.

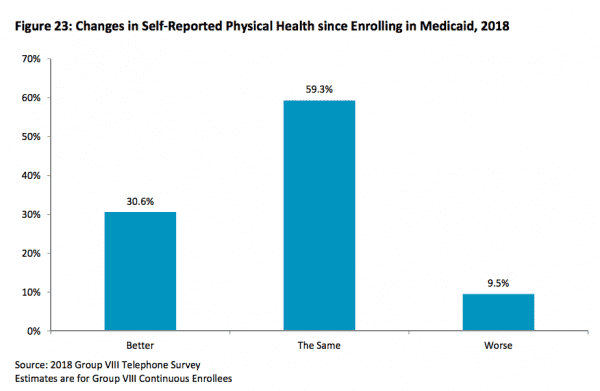

You might ask, in conclusion, how the Medicaid enrollees themselves are feeling about this five-year health care experiment.

The answer: A lot of them feel the same physically, which is a reminder of how difficult it can be to truly affect people’s health. But they are far, far more likely to feel better than to somehow feel worse now that they have health insurance.

Remember: 17 states have still refused to expand Medicaid in Obamacare’s fifth year, leaving an estimated 2.2 million people uninsured because they can’t get the coverage the law intended them to have.

This story appears in VoxCare, a newsletter from Vox on the latest twists and turns in America’s health care debate. Sign up to get VoxCare in your inbox along with more health care stats and news.

vox-mark

VoxCare

Subscribe

By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Policy and European users agree to the data transfer policy.

For more newsletters, check out our newsletters page.

Join the conversation

Are you interested in more discussions around health care policy? Join our Facebook community for conversation and updates.

Sourse: vox.com