Last week, a county in western Nebraska tried something new. With permission from Secretary of State John Gale, Garden County conducted its May 15 primary election entirely by mail. A ballot was mailed to every registered voter, to be returned, either by post or at a drop box, by the day of the election.

That simple change boosted voter turnout in Garden County to 58.7 percent. The average for all other Nebraska counties? 24.3 percent — less than half that. (Oh, and the county’s results were available less than an hour after the polls closed.)

It was a little like what happened last month, when the city of Anchorage, Alaska, home of almost half the state’s population, held its first vote-by-mail city elections. Voter turnout hit 34 percent, breaking a record set in 2012. (Among other things, Anchorage residents rejected an anti-transgender bathroom measure.)

The month before that, officials in Utah County, Utah (home of Provo), tried to undo a switch to vote-by-mail, reverting to voting booths so that, they plaintively noted, they could use all that voting equipment they’d bought in years prior. But city leaders and residents flipped out, protested, and basically forced the officials to change it back to mail votes.

The moral of all these stories is the same: Vote-at-home (VAH) systems, using old-fashioned postal mail and paper ballots, are just better. They increase turnout and make voting a more positive experience. If progressives are looking for a simple, powerful way to reform voting and boost democracy, well, there’s one sitting right in front of them.

As these scattered experiments show, VAH may not exactly be sweeping the nation, but it is, let’s say, tiptoeing steadily across the nation. Currently, three states are 100 percent VAH: my home state of Washington, Oregon, and Colorado. (The former secretary of state of Oregon, instrumental in implementing VAH there, is Phil Keisling, who founded the Vote at Home Institute.)

In addition, 27 of 29 Utah counties, 31 of 53 counties in North Dakota, five counties in California, and, now, Anchorage use VAH. Notably, these are not simply liberal islands — as the Utah County story shows, VAH exists, and is popular, in blue, red, and purple areas. Nationally, roughly 33 million ballots, or 25 percent of the total in the 2016 presidential election, were cast by mail.

VAH works, it’s popular, and it’s past time reformers gave it the attention it deserves. I’ve made the case before at length; here, I’ll just hit a few of the highlights.

Vote-at-home systems increase turnout

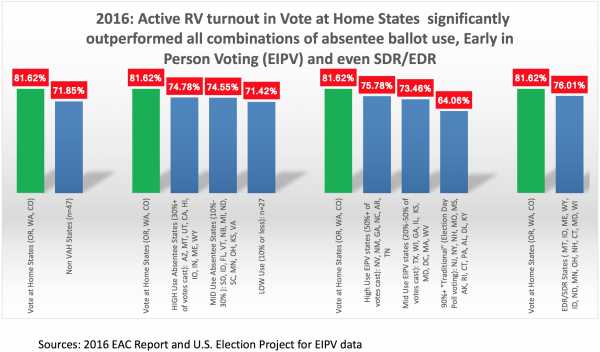

Research shows that average turnout in the three VAH states beats virtually any combination of other states:

(SDR is same-day registration; EDR is election-day registration.)

Research released in April by the National Vote at Home Coalition (NVAHC) looked at turnout across Minnesota and North Dakota, which allow VAH in some special circumstances but not others, offering a convenient real-world experiment with a control group.

The main finding is that VAH increases turnout in all cases, in all precincts and elections in which it’s available:

This is in keeping with previous research, which finds that VAH increases turnout somewhat during presidential elections, substantially more in midterms, and even more in primaries. In other words, it increases turnout precisely in the contests that typically see lower turnout.

It’s not difficult to imagine why — the ballot showing up in your mail is a pretty helpful reminder that there’s an election happening, and filling it out is a pretty low-impact ask. Plus, you can take your time filling it out, doing research as you go, which is especially helpful in some of the more obscure local elections.

Vote-at-home systems are cheaper

The transition to a VAH system — changing procedures, disposing of old equipment (remember the voting machines Utah County already bought) — can cost a chunk of money up front, but over time, VAH increases efficiency and reduces costs.

In 2016, Pew did a close analysis of Colorado’s experience shifting to VAH after sweeping 2013 election reforms. Among its findings: “Costs decreased by an average of 40 percent in five election administration-related categories.”

The state needed fewer poll workers (from 16,000 in 2008 to 4,000 in 2014) and fewer polling locations (from more than 1,800 to about 300). The use of provisional ballots dropped by 98 percent, which ended up yielding a huge reduction in printing costs. Overall, “counties spent an average of $9.56 per vote in 2014, down from $15.96 in 2008.”

Vote-at-home systems are safer

In my experience, people unfamiliar with VAH have some odd but fervent fears about it, especially around fraud and abuse — the idea that, out of the public eye, it will be easier to forge a signature or coerce another voter.

But either of those acts is a felony in VAH states, so the perpetrator would be risking a five-year jail term to change … one vote. It’s difficult to imagine how it could be done on a scale that would make a difference in even a modestly sized election.

We don’t have to imagine, though: As I said, about a quarter of all votes were cast by mail in 2016. Absentee ballots have long been available in dozens of states. Since 2000, overall, about a quarter-billion votes have been cast by mail. Thus far, there have been virtually no documented incidents of coercion or abuse. As NVHC notes in a white paper on this subject, “Oregon has mailed-out more than 100 million ballots since 2000, with about a dozen cases of proven fraud.” That’s a 0.00000012 percent rate of fraud.

Meanwhile, as the New York Times Magazine detailed in a recent piece, there’s basically no such thing as a hacker-proof electronic voting machine. The ones in use in the US certainly don’t fit that bill. “In the 15 years since electronic voting machines were first adopted by many states,” reporter Kim Zetter writes, “numerous reports by computer scientists have shown nearly every make and model to be vulnerable to hacking.”

Knowing what we do now about the world’s programmers and what they have wrought, do we really want to turn democracy itself over to their tender ministrations?

Perhaps, in the case of voting, it’s best to go simple and analog: a signed slip of paper for every vote.

Vote-at-home systems are just better

I live in a VAH state (Washington), so I know from personal experience that there are intangibles, benefits of VAH that can’t be quantified but must be apprehended phenomenologically.

Don’t let anybody fool you with this nonsense nostalgia about bumping into neighbors at the polling place, seeing all the “I voted!” stickers, talking to the nice old ladies at the card table, and feeling a stirring of old-fashioned civic fraternity.

I mean, I know that stuff can happen; I’ve experienced it. But most of the time, for most people, voting in the US is a big bunch of bullshit hassle. It’s been made a hassle on purpose — and not for all people equally, but, like so many things, disproportionately for the poor, minorities, young people, and students.

Just the idea that in 2018, people have to schlep down to a gym or something between particular hours on a particular weekday and stand in line for hours to poke at choices on a touchscreen, all while being monitored by creepy onlookers … it’s an insult to modernity, all of it. We can do better.

Here’s how voting goes at my house: We sit around the dinner table as a family, walking through the ballot, researching and talking about the options and issues, explaining our choices. Then my wife and I sign, seal our envelopes, and drop them in the mail. I look forward to it!

Everyone in America deserves the same option. It’s just civilized. That’s why voters who get VAH like it and want to keep it. I know I can’t imagine going back to the old way, no matter how nice the stickers are.

Vote-at-home should be at the top of any progressive election reform list

Election and voting discussions in the US can get complicated, fiddling around the margins with registration deadlines and different forms of ID. It’s the kind of complexity that serves to obscure the constant low-level injustice of the status quo.

Progressives need a simple, powerful, and easily communicated electoral reform to cut through the complexity and rally voters. I think national VAH fits the bill, and as it happens, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden already has a bill written and ready to go: the Universal Right to Vote by Mail Act.

Such a reform would benefit almost everyone, but particularly populations that have difficulty getting to a polling place on a weekday (working mothers, the ill or elderly, low-income, etc.).

What’s more, its benefits are easily explained. You can sit and fill out your ballot when it’s convenient, doing your own research, talking to friends and family if that’s your thing, and then drop it in the mail or a drop box at your leisure. For every single vote, there will be a signed piece of paper that matches a signed voter registration card — easy to count, easy to recount.

VAH is safe, efficient, and small-D democratic. It’s a way to cut through almost all the hassle of voting with a single simple, durable reform. Sounds good to me — I vote yes.

Sourse: vox.com