The history of the Iowa caucuses (and their downfall?), briefly explained.

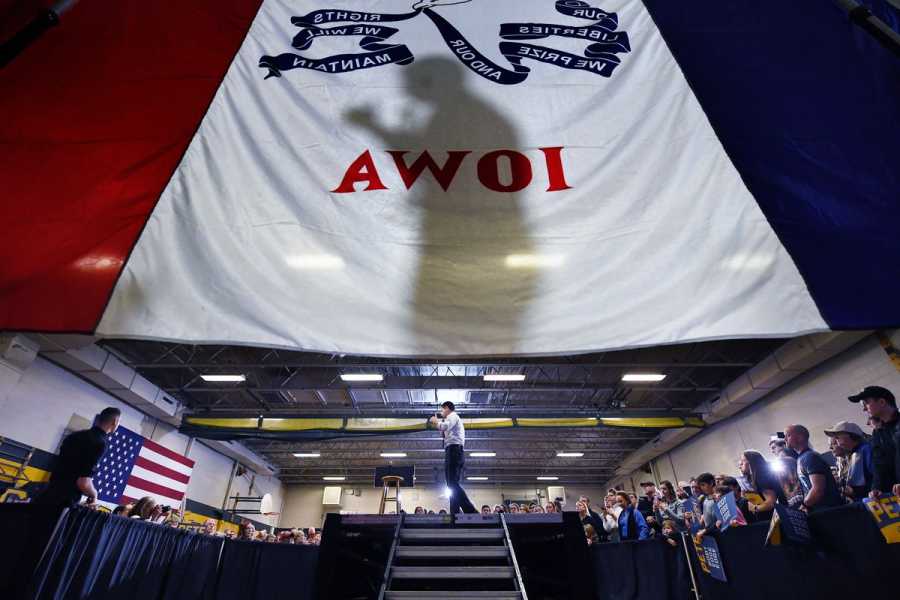

Pete Buttigieg appears at a campaign event at Northwest Junior High School in February 2020 in Coralville, Iowa. Matt McClain/The Washington Post via Getty Images Nicole Narea covers politics and society for Vox. She first joined Vox in 2019, and her work has also appeared in Politico, Washington Monthly, and the New Republic.

Welcome back to the Iowa caucuses — or at least, a version of them.

The caucuses, a contest in which voters gather in local meetings run by their state parties to say who they’d prefer to be their presidential nominee, have been an institution in modern presidential campaigns since the 1970s for Democrats and Republicans.

That’s changing this year with Democrats’ adoption of a new primary calendar that no longer puts Iowa first and rule changes that allow voters to state their presidential preference via a mail-in process.

For Republicans, who are holding their Iowa caucuses on January 15, the caucuses’ significance as the nation’s first presidential contest remains. However, the political circus is already much quieter than in past years in Iowa, where both Democrats and former President Donald Trump have opted not to campaign much, perhaps in part due to President Joe Biden and Trump’s massive leads in the polls. Though things could change again in 2028, the relatively sleepy season suggests that the heyday of the caucuses may be over.

For the last half-century, the caucuses have catapulted candidates to their party’s nomination or even the White House — and doomed candidates who underperform expectations. For the Republicans looking to displace Trump as the decisive GOP frontrunner, a dominant performance in Iowa similarly poses a potential make-or-break opportunity this year. But none of them appear positioned to pull it off.

In many ways, it’s odd that Iowa was ever key to how Americans pick a president, and is even more so now. Iowa is no longer as representative of the nation as it once was, or a swing state, or the home of many deep-pocketed donors. It has only six electoral votes to boot. But because of its time-honored status as the first contest on the presidential nominating calendar and because the media and candidates themselves ascribe meaning to it, it’s become, by default, a major presidential testing ground.

While state party officials have recently fought hard to keep Iowa’s place on the calendar, at first “there was no grand plan that put Iowa ahead of other states,” said Rachel Paine Caufield, director of the Iowa Caucus Project and a political science professor at Drake University. “It’s a quirk of history.”

Ironically, the modern Iowa caucuses were an accidental product of reforms designed to make electoral politics more inclusive — the same objective that some Democrats now cite in seeking to put the tradition to rest.

The reforms that paved the way for the Iowa caucuses

Besides a one-time flirtation with primaries in 1916, Iowa has always held caucuses. But the modern Iowa caucuses as we know them began amid the tumult of the 1960s and against the backdrop of the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War.

Democrats at that time were deeply divided. In 1968, then-President Lyndon B. Johnson decided against running for a second full term due to his involvement in the unpopular war. Sen. Eugene McCarthy, a staunch critic of the war, and Hubert Humphrey, at that point Johnson’s vice president and the establishment pick, entered the race representing opposing factions. So, too, did Robert F. Kennedy, who seemed poised to unite Democrats after winning the California primary but was ultimately assassinated, leaving the party in further disarray ahead of the August convention in Chicago.

At that point, conventions were largely controlled by state and party bosses. They handpicked delegates to attend the convention, allegedly offering money and power in exchange for support of their preferred candidate, who was not necessarily the voters’ preferred candidate. Only 16 states even held primary elections or caucuses at the time, and they were “for the most part beauty contests… that gave candidates some exposure but little political clout,” as the late historian John C. Skipper wrote in his book, The Iowa Caucuses: First Tests of Presidential Aspiration, 1972-2008.

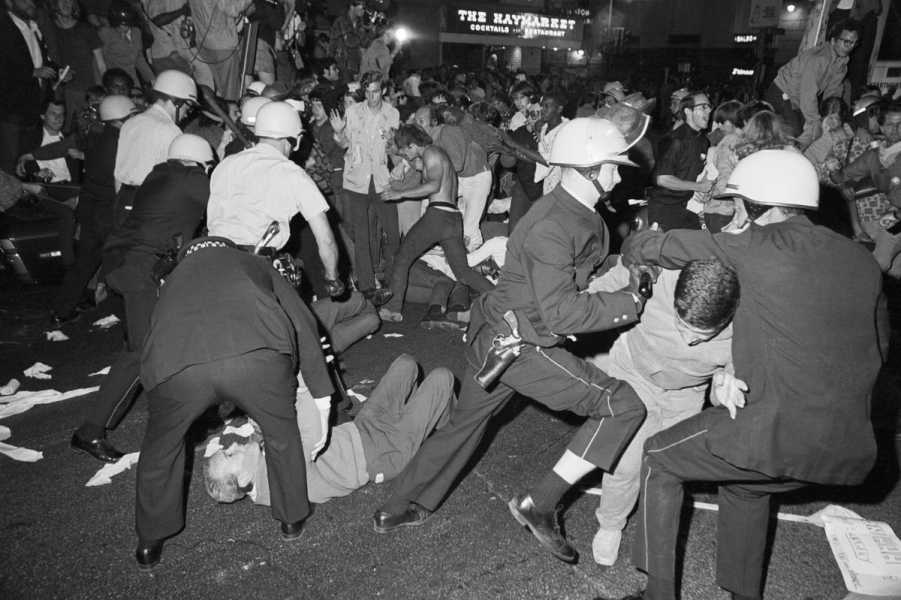

Humphrey had entered the race too late to run in the primaries, and McCarthy supporters alleged that the establishment wing of the party was purposefully denying them credentials to attend the convention. Protests broke out in the city streets led by young anti-war activists, and police violently put them down and conducted mass arrests.

Police and demonstrators are in a melee on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Bettmann/Getty Images

Black civil rights activists who fought for the passage of the Civil Rights Act (and later the Voting Rights Act) had been previously shut out of the convention by party bosses, which perpetuated a broader sense of disenfranchisement. Many youth, women, and other minority groups who were also “tired of the politics-as-usual maneuvering of power brokers,” were frustrated by how the convention was conducted, Skipper wrote.

Eventually, Humphrey won the Democratic nomination with scarce support from delegates who were women, Black, or under the age of 30, and Republican Richard Nixon went on to defeat him to become president. Democrats attributed Humphrey’s loss to a lack of buy-in from key parts of the party’s emerging coalition and didn’t want a repeat of that mistake. A group was therefore formed to reform the Democratic nominating process ahead of the 1972 election.

“One of the things that the party wanted to do was democratize the process to make sure that more young people and more people of color were involved in the process,” Paine Caufield said.

The group of reformists determined that “party bosses could no longer pick convention delegates,” “states could not rig the rules to prevent registered Democrats from participating in the process,” and states should “create systems of open primary elections or [local] party caucuses to determine their delegates,” Skipper wrote.

While that caused many states to establish primaries, Iowa was already successfully running caucuses, and Democrats kept them in place — with some modifications designed to make them more inclusive. That included establishing a four-step caucus-to-convention process to maximize local participation: electing county delegates, then district delegates, then state delegates, and finally sending those delegates to the national convention.

They also adopted a 15 percent threshold of support for a candidate to be considered viable in the caucuses, and required that the public be provided with adequate notice of events as well as paper copies of the party rules, platform, and other information that the cash-strapped party printed on an old, slow mimeograph machine. To make all that happen in time for the national convention, state Democrats scheduled the caucuses for late January. Thus, Iowa became the first contest in the nation for Democrats.

“Iowa became first in the nation pretty much as an accident of the calendar,” said Peverill Squire, a professor of political science at the University of Missouri and author of The Iowa Caucuses and the Presidential Nominating Process.

The state and national parties wouldn’t realize how significant that was at first — an oversight that would be short-lived.

Jimmy Carter created the blueprint for success in Iowa

In 1972, the first presidential election under Democrats’ new rules, no one really paid attention to the now first-in-the-nation Iowa caucuses. Candidates didn’t spend much time there, and neither did the media. It was a time when campaigns were less nationalized, and it wasn’t expected that a presidential candidate would travel to every state. But Sen. George McGovern, who finished third in the caucuses in the first sign that he had any significant amount of support, went on to win the Democratic nomination.

Republicans took notice of this. They hoped to capitalize on McGovern’s perceived momentum from Iowa, and moved their caucuses to the same day as the Democrats, also first on their nominating calendar, in the 1976 election cycle.

That same year, Jimmy Carter became the first candidate to demonstrate that showing up often and early in Iowa could lead to breakout success. Many presidential hopefuls have since tried to replicate his strategy.

Running in 1976 as a widely unknown former governor of Georgia, Carter sought to use Iowa as a proving ground on a national stage. He was the first candidate to campaign in Iowa with the intention of generating early buzz. He campaigned for a total of 17 days there, starting about a year before the caucuses, and engaging in the kind of unglamorous grassroots politicking that many now recognize as characteristic of Iowa. He talked to people in living rooms, labor halls, and livestock confinements and accepted pizza and car washes as speaking honorariums, Skipper wrote.

“I came [to Iowa] looking for a TV camera,” Carter later recalled. “I never found it.”

Carter also took advantage of media hunger for early, concrete results, even if the results of the 1976 caucuses didn’t actually say much (there were more uncommitted voters than those who supported Carter.) But he was declared the night’s winner by the media, invited on several major talk shows in New York the next day, and ultimately won the presidency. Every underdog candidate since has hoped to “pull a Jimmy Carter,” as journalist Alexandra Pelosi has described it.

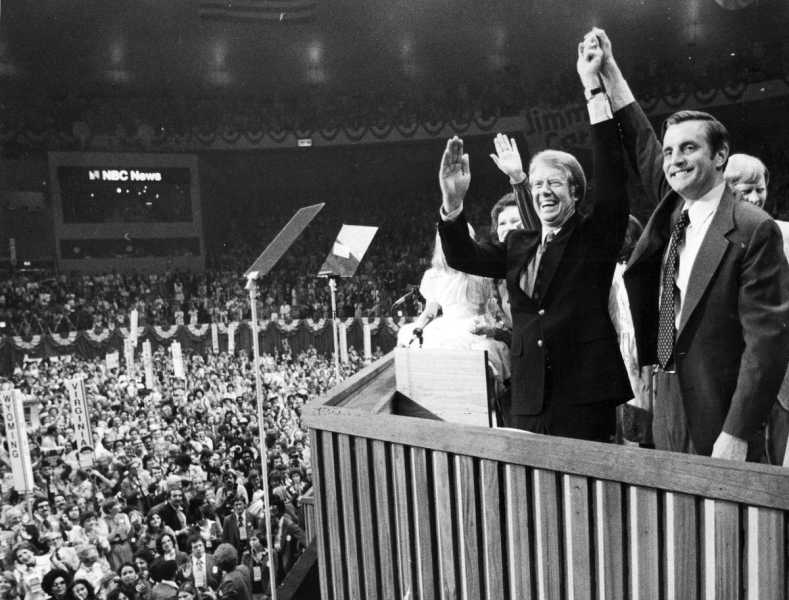

Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale raise hands to an enthusiastic crowd after their acceptance speeches at the 1976 Democratic National Convention at Madison Square Garden in Manhattan. Newsday LLC/Getty Images

“The ethos of the Iowa caucus is really built on that mythology of Jimmy Carter’s campaign,” Paine Caufield said. “We think of it today as this folksy tale about a hard-working candidate, but he played it well.”

Iowa’s mattered for years — does it matter anymore?

From George W. Bush to Mitt Romney, candidates have seen their dreams realized or crushed in Iowa — even if it’s not a super accurate predictor of success in winning the nomination or the race to the White House.

In addition to Carter, only two other presidents since 1976 have won the Iowa caucuses: Barack Obama in 2008 and Bush in 2000. Other presidents have gone on to win despite losing the caucuses: Ronald Reagan in 1980, George H.W. Bush in 1988, Trump in 2016, and Biden in 2020.

“The record of the Iowa caucuses on predicting nominees and winners of the presidential race is pretty weak,” Squire said. “But it’s the only story in town up until the night of the caucuses, and then the circus moves on to New Hampshire.”

Sen. Barack Obama, with his daughters Malia and Sasha and his wife Michelle, visited the Iowa State Fair in Des Moines, for a 2007 campaign stop. Charles Ommanney/Getty Images

In the 1970s and 1980s, Iowa played a more prominent role in weeding out weak candidates and in shaping the expectations game. “If you didn’t do well in Iowa, you tended to find that your candidacy was over at that point. That’s probably not the case anymore,” Squire said. That may be partially because campaigns and fundraising have become more nationalized over time, with no one state exerting singular influence.

Still, the frenzy around Iowa does have an impact on the outcome of primaries. A National Bureau of Economic Research study of the 2004 election found that voters who cast ballots in early-voting states such as Iowa had up to 20 times the influence of late voters in the selection of candidates. Early voters are able to narrow the field, boost longshot candidates, and dim the prospects of perceived frontrunners in a way that voters who cast their ballots once the primary is all but decided are not.

A large part of early voters’ power may come down to the way in which they help direct media attention. Researchers David Redlawsk, Caroline Tolbert, and Todd Donovan concluded in their book Why Iowa? that, based on data from 1976 through 2008, “media coverage of the candidates before and immediately after the Iowa caucuses significantly influences a candidate’s overall performance in primaries nationwide.”

Now that Democrats have decided to move their focus away from Iowa following a bungled caucus in 2020 that led to delays in reporting the results and Biden expressing his preference to change the calendar, however, that impact may no longer be what it once was.

Some Iowa Democrats are holding out hope that they can restore Iowa’s Democratic caucuses to their former glory in 2028 when, unlike this year, they will actually matter in picking a nominee. But for many progressive Democrats, who argue that the now decidedly red state doesn’t represent the party’s diverse base and that the caucus process excludes all but the most hardcore partisans, Iowa’s time is over. At the moment, the plan for the 2028 caucuses is still up in the air, and it’s not clear if Democrats will keep their current calendar.

“The road that Jimmy Carter took to the nomination is gone,” Squire said. “The Iowa caucuses now are more of a media and advertising event.”

Sourse: vox.com