It’s tempting for liberals to see President Trump’s executive order suspending family separations as a victory. The past few days of public outrage, on this theory, put so much pressure on the president that he was forced to cave by Wednesday afternoon.

“In the face of overwhelming public pressure, Trump relented and agreed the policy his administration had deliberately engineered was a real policy, and that he could change it, and would,” New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait writes. “It is a sign that the peripheral elements of Trump’s coalition have a breaking point.”

The notion that Trump has really “ended” family separation is questionable as a matter of law. Trump’s executive order doesn’t actually ban the practice; it merely directs the Department of Homeland Security to detain migrant families together rather than separating them. But there are serious questions about the legality of such a policy; if it gets overturned by the courts, then it’s entirely possible that family separations could begin again.

But the “backlash works” analysis also skips over a more fundamental political question. The truth is that huge numbers of Americans — mostly Republicans — were willing to back the family separations policy. They’re even more excited about the underlying policy of arresting every undocumented individual who crosses the border, the so-called “zero tolerance” policy that gave rise to family separation in the first place.

What’s most telling about this episode isn’t Trump stepping back in the face of public outrage. It’s the millions of Republican who were — are — willing to support an obviously cruel immigration policy. And that, in turn, points to perhaps the deepest problem in American politics in the Trump era: The lethal conjunction of white identity politics and partisanship has made the Republican Party willing to sanction injustices that had previously been unthinkable in modern America.

Republicans back Trump’s immigration policies — even the ones they used to hate

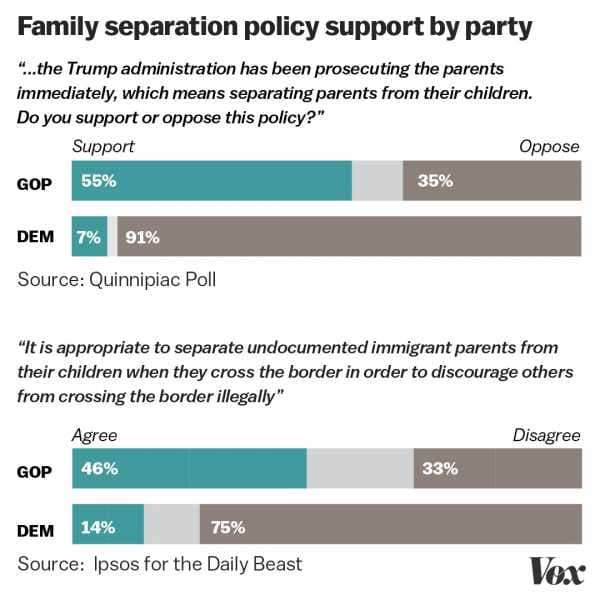

The polling on family separation has been remarkably consistent. A majority of Americans oppose it, driven by nearly unanimous opposition among Democrats and strong opposition among independents. But Republicans generally support it by a significant margin:

There are two ways to parse this data. The optimistic take is that Republicans are more divided than usual. Typically, Republicans favor Trump policies by truly massive margins. The fact that on this, support is hovering around 50 percent approval, with a substantial minority disagreeing, provides support for Chait’s thesis that the “peripheral elements” of Trump’s coalition could break from him.

The more pessimistic take is that’s still millions of American people backing a policy that by definition means separating children from their parents for an unknown period of time — perhaps permanently. That is morally grotesque. The fact that most Republicans seem to favor the policy is a testament to the degree to which Republican moral thinking is shaped by partisanship and Donald Trump’s position.

What’s more, the debate over family separation policy is in its relatively early stages. And there’s good reason to believe that if Trump comes back to the idea, it will grow more popular with Republicans — not less.

Look, for example, at the shift in Republican opinion on the Muslim ban. In December 2015, when Trump first announced his proposal for a “total and complete shutdown” on Muslim immigration, scores of prominent Republicans — including future Vice President Mike Pence — condemned the idea in roughly the same morally charged terms some Republican leaders have used to discuss family separations. A Wall Street Journal/NBC poll at the time found that GOP primary voters were evenly split on the idea, with 39 percent opposing it and 38 in favor.

By March 2016, when it became clear that Trump was likely to be the GOP standard-bearer, things changed. Exit polls from primaries in five states — Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, Missouri, and Illinois — found that fully two-thirds of Republican voters supported a Muslim ban. When Trump actually implemented a version of the Muslim ban in January 2017, the now-infamous “travel ban,” Republicans overwhelmingly backed him. A June 2017 Politico poll found that 84 percent of Republicans supported the travel ban — and a scant 9 percent opposed it.

What happened with the Muslim ban is obvious. The clearer it became that supporting it was a core Trump position, the clearer it became that being a Trump supporter in good standing required backing the travel ban. When Trump became the Republican nominee, and subsequently president, Republican partisan identity became more about backing Trump.

George C. Edwards III, an eminent scholar of presidential rhetoric at Texas A&M University, examined data on five separate policy debates under three recent presidents (Obama, George W. Bush, and Reagan) in a 2015 paper. He found clear evidence that the more closely a policy is identified with the president — particularly through public comments by the president himself — the more likely people from the president’s party are to support it.

“The president’s association with a policy is an especially powerful signal to those predisposed to support his initiatives,” Edwards writes. “By reinforcing his partisans’ predispositions, presidents can counter opposition party attacks and discourage his supporters from abandoning him. In addition, co-partisans appear to be resilient in returning to support after periods of bad news.”

The family separation debate didn’t actually go on for very long, so opinion on it didn’t have time to harden along partisan lines. The Trump administration sent profoundly mixed signals about what to think about it — sometimes saying it’s a shame and Democrats’ fault, and sometimes saying it’s necessary to deter more undocumented migration. Under these conditions, with the moral shock of the headlines still feeling fresh and some prominent Republicans like Laura Bush still willing to condemn the policy, it’s easy to see why some Republican voters felt comfortable opposing Trump.

But despite all that, you still had Republicans supporting a morally obscene policy — by a relatively significant margin.

If the Trump administration were to resume family separations, with Trump himself presenting a sustained defense in public appearances and tweets, Republicans most likely would rally around him the same way they came to support the (also morally obscene) Muslim ban. The scary truth is that if Trump had stayed the course on this one, allowing the media attention and public outrage to dissipate, he probably could have gotten away with it.

Trump has hopelessly intertwined Republican politics with white identity

But the issue here isn’t just partisanship. It’s that in going after overwhelmingly Latino immigrants from Central America, Trump is playing on his political home turf.

A 2015 book by two political scientists, Marisa Abrajano and Zoltan Hajnal, looked closely at the way mass Latino immigration was shifting American politics. The book is long and detailed, but Abrajano wrote an accessible summary of its arguments for the Brookings Institution (read it here). The core conclusion, she explains, is that the influx of Latino immigration has driven a large number of white voters into the Republican Party. “Whites who are fearful of immigration tend to respond to that anxiety with a measurable shift to the political right,” she writes.

This effect seems to tracks media coverage. When you have people in the news talking about the threat posed by immigration — like, say, the president talking about how Latino migrants are responsible for gang violence — Republicans benefit. “When media coverage of immigration uses the Latino threat narrative,” Abrajano writes, “the likelihood of whites identifying with the Democratic Party decreases, and the probability of favoring Republicans increases.”

A different group of researchers polled white Americans on how their view of diversity affected their likelihood of voting for Trump. They found that when whites were reminded that America was becoming an increasingly black and brown country, they were more likely to support Trump and favor restrictions on immigration.

“Reminding White Americans high in ethnic identification that non-White racial groups will outnumber Whites in the United States by 2042 caused them … to report increased support for Trump and anti-immigrant policies,” the researchers conclude.

This is the devilish problem of the Trump era in a nutshell. The most grotesque-seeming parts of Trump’s presidency — his crackdown on undocumented migrants, the Muslim ban, his shocking moral equivalencies during the white supremacist rallies in Charlottesville, Virginia — tap into the forces that are most responsible for making him president. The stories of separated families in the media rend the hearts of neutral observers, but Trump’s most hardcore supporters may very well have the opposite reaction.

This intersects in a particularly dangerous way with partisanship. If Trump can maintain support from his hardcore base, enough to hold majority support in the GOP, he won’t actually have to cave immediately — and the longer and more loudly he fights for a policy, the more support for it will become part of GOP orthodoxy.

It’s simply a fact that Trump’s racial politics are popular with millions of white Americans; even a policy as vicious as the family separations attracted significant amounts of support. It’s also a demonstrable fact that the strength of GOP partisanship means that, in theory, Republican presidents should be able to attract the support of the party base and, as a result, its political establishment. Those two facts mean that Trump will pretty much always be able to get them to back his attacks on members of minority groups, given time and effort.

Let’s be clear: Ending family separation (for now) is a good thing, and it’s understandable that some liberals may be tempted to count this as a win. But that the separations happened at all, and that millions of Americans were perfectly fine with them, is something that should trouble us all.

Sourse: vox.com