In session after session behind closed doors last month, House Republicans repeatedly suggested that President Donald Trump’s push for Ukraine to launch a series of criminal investigations into Joe Biden and alleged interference in the 2016 presidential election was about rooting out corruption, not investigating his political rival.

Interested in Impeachment Inquiry?

Add Impeachment Inquiry as an interest to stay up to date on the latest Impeachment Inquiry news, video, and analysis from ABC News.

Impeachment Inquiry

Add Interest

According to some of Trump’s staunchest allies, it was Ukraine, not Russia, that truly meddled in American democracy three years ago.

“Public reporting shows how senior Ukrainian officials interfered in the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign in favor of Secretary Clinton and in opposition to then-candidate Trump,” Republicans wrote in a memo of “key points” distributed Tuesday ahead of the House impeachment inquiry’s first open hearings this week.

But behind closed doors, many of the witnesses who recently testified to House investigators balked at any such comparison to Russia’s efforts.

“We’re talking about a completely different scale of interference,” Army Lt. Col. Alex Vindman, a National Security Council expert on Ukraine, testified.

(MORE: Trump-backed allegations against Biden ‘not credible,’ testified US official now touted by Trump)

At the Kremlin’s direction, Russia’s intelligence services waged a pro-Trump disinformation campaign on social media and secretly stole tens of thousands of private emails from the Democratic National Committee, the U.S. intelligence community concluded.

That government-backed campaign was a “deep” and “insidious effort to undermine a foreign country’s elections,” Vindman said. In fact, last year the Justice Department indicted 25 Russian operatives for their alleged roles in election interference during the 2016 campaign – none has been taken into custody yet.

“What a couple of actors in Ukraine might do in order to tip the scales in one direction or another is very different,” Vindman noted.

Nevertheless, based on the new Republican memo, questions to witnesses behind closed doors, and the Republicans’ proposed witness list, Trump’s House allies are likely to promote such instances during this week’s hearings.

As Republicans see it, Ukrainian “interference” in the 2016 campaign contributed to Trump’s “deep-seated” skepticism of Ukraine, any delay in Trump engaging with Ukrainian leadership earlier this year was not about pressuring them to launch politically-charged investigations, it was about Trump’s “reasonable” concerns, according to the Republican memo distributed Tuesday.

Here are the instances of alleged Ukrainian interference that Republicans might raise during this week’s public testimony:

Ukrainians disclosed the ‘black ledger’

In August 2016, three months before the U.S. election, a Ukrainian anti-corruption office and a Ukrainian journalist-turned-lawmaker, Serhiy Leshchenko, released records showing that Trump’s campaign chairman, Paul Manafort, had received millions of dollars in payments suspected of coming from ill-gotten proceeds in Ukraine. The records – part of a so-called “black ledger” – were found at the past estate of Viktor Yanukovych, the former Ukrainian president who hired Manafort as a political consultant and then fled to Russia in 2014 amid allegations of corruption.

Lucas Jackson/Reuters, FILE

Former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort is escorted into court for his arraignment in New York Supreme Court in New York, June 27, 2019.

The release of the “black ledger” forced Manafort to resign from the Trump campaign. Leshchenko has given conflicting accounts of what drove him to make the documents public, but in September he insisted in The Washington Post that he was “angry at Manafort” for protecting a corrupt leader and “was motivated by the desire for justice.”

(MORE: How Giuliani’s associates, promoting a foreign agenda, used Trump-friendly media to get a US ambassador removed)

Whatever his motivation, Leshchenko and the head of the anti-corruption office were investigated and convicted in December 2018 of violating Ukrainian law by releasing the documents. Meanwhile, around the same time, Ukraine’s top prosecutor was also feeding allegations about former vice president Joe Biden to Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, who then launched a shadow campaign to have the allegations investigated.

Several months after Leshchenko was convicted, a Ukrainian appeals court threw out the case and overturned the conviction. But in closed-door testimony last month, Republicans wanted to know why U.S. diplomats didn’t do more to investigate Leshchenko’s actions.

“Here we have a conviction of U.S. meddling, and you just viewed that as not being significant and you just dismissed it?” Rep. Gordon Perry, R-Penn., asked Marie Yovanovitch, the former ambassador to Ukraine who was removed after Giuliani and others launched what she and her colleagues called a “smear campaign” against her.

Yovanovitch said it was “our view” that the case against Leshchenko wasn’t “credible.”

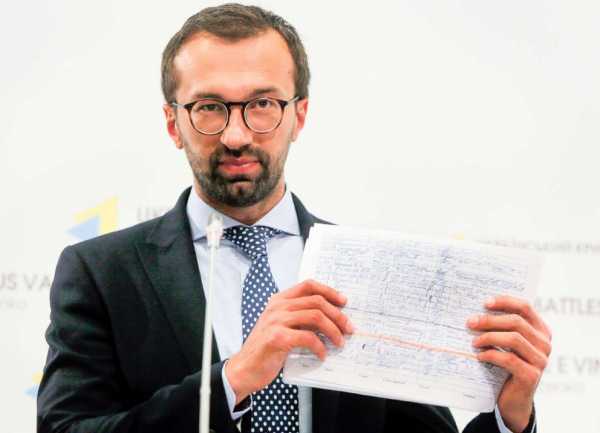

Efrem Lukatsky/AP, FILE

Serhiy Leshchenko shows a copy one of the once-secret accounting documents of Ukraine’s pro-Kremlin party that were purporting to show payments of $12.7 million earmarked for Paul Manafort, during a news conference in Kiev, Ukraine, Aug. 19,2016.

“I didn’t believe the charges,” she said. “I thought that they were politically motivated … [And] I really felt that we wanted to stay away from what seemed to be internal Ukrainian political fights kind of using us.”

In March, conservative U.S. media began promoting claims that the Manafort-related documents made public may have been fake. The allegations were investigated and the documents were “declared to be valid,” but questions about them were still “in the public domain,” Volker testified, without specifying who validated the documents.

“Can you understand why [Trump] would want Ukraine to investigate why perhaps these ledgers were fabricated, if he had that belief?” a House Republican investigator asked Volker.

“Yes,” Volker responded.

Asked during his testimony whether Leshchenko’s actions would “constitute election interference” as it’s currently understood, Vindman said: “I don’t think it would.”

A U.S. federal jury last year convicted Manafort of financial crimes related to his work for Ukraine’s disgraced former president. The charges were brought by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, who had been investigating Russia’s interference in the 2016 election.

Ukrainian’s ties to ‘dossier’ firm

Republicans are also interested in Leshchenko because he was once a source of information for Fusion GPS, the research firm behind the controversial “dossier” that alleged members of Trump’s campaign were coordinating with the Russian government to interfere in the 2016 election.

A former researcher at the firm, Nellie Ohr, told lawmakers last year that Fusion GPS would pursue leads provided directly by Leshchenko.

Ohr’s husband, Bruce, is the senior Justice Department official who acted as a conduit between the FBI and the author of the “dossier,” former British spy Christopher Steele. Republicans now want Democrats to call Ohr to testify in the impeachment probe.

Victoria Jones/PA via AP, FILE

Christopher Steele, the former MI6 agent who set up Orbis Business Intelligence and compiled a dossier on Donald Trump, is seen in London, March 7, 2017.

DNC contractor connected to Ukrainians

Republicans have also repeatedly asked in recent closed-door sessions about Alexandra Chalupa, who during the 2016 presidential campaign worked as a contractor for the Democratic National Committee running what she called “an ethnic engagement program.”

Years earlier, while working for a different client, the Ukrainian-American based in Washington began researching Manafort’s ties to Ukraine, and after Trump announced his candidacy in late 2015 she began looking at Trump’s ties to Russia, occasionally sharing some of her findings with officials at the DNC, Chalupa later told Politico in a 2017 interview.

In March 2016, she also shared some of her findings with Ukraine’s ambassador to the United States, Valeriy Chaly, she told Politico.

And in an email two months later, she told a DNC spokesman that she had been “digging into Manafort” and was “working with” a prominent U.S. journalist whom she “connected” with “the Ukrainians.”

That email was among the tens of thousands of internal emails stolen from the DNC in 2016 and published online.

Bloomberg via Getty Images, FILE

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters stands in Washington, D.C., Oct. 9, 2018.

In a statement to CNN at the time, Chalupa insisted, “I was not an opposition researcher for the DNC, and the DNC never asked me to go to the Ukrainian embassy to collect information.” And in May, Chaly told The Hill newspaper that the Ukrainian embassy “got to know Ms. Chalupa because of her engagement with Ukrainian and other diasporas in Washington, D.C., and not in her DNC capacity. We’ve learned about her DNC involvement later.”

Chalupa’s interest in Manafort was “her own cause,” and the embassy “refused to get involved in any way,” Chaly added.

Still, her efforts have raised concerns among Republicans, who want Chalupa to testify this week.

So “[Chalupa] may be another data point to the president’s uncomfortable posture towards Ukraine?” a House Republican investigator asked Volker.

“It’s possible,” Volker responded.

Public comments about Trump

In closed-door testimony last month, Republicans wondered what U.S. diplomats knew about public criticism of Trump from Ukrainian government officials.

Among other episodes, Republicans asked about an August 2016 op-ed published by Chaly, then the Ukrainian ambassador, who strongly criticized then-candidate Trump’s pro-Russia rhetoric. In the op-ed, Chaly said Trump’s comments “call for appeasement of an aggressor.”

Similarly, Ukraine’s minister of Internal Affairs, Arsen Avakov, posted what one House investigator described as “disparaging remarks about the President on Twitter and Facebook.”

But Vindman rejected claims that those comments reflected any type of election interference from Ukraine, insisting acts of election interference “are not open public displays.”

Drew Angerer/Getty Images, FILE

President Donald Trump exits the Oval Office and walks toward Marine One on the South Lawn of the White House in Washington, D.C., Nov. 6, 2019.

In her testimony to House investigators, former National Security Council staffer Fiona Hill, an expert on Russia, said senior White House officials, including then-homeland security adviser Tom Bossert, tried early on in Trump’s presidency to tell Trump that “the alternative theory” of Ukrainian election interference was false.

“I’m aware of the [allegations], but that doesn’t mean that that amounts to an operation by the Ukrainian Government,” she said.

Bossert, now an ABC News contributor, recently said the “conspiracy theory” of Ukrainian election interference “has got to go.”

“It is completely debunked,” he told ABC News’ George Stephanopoulos on “This Week” in September. “They have to stop with that. It cannot continue to be repeated in our discourse.”

Sourse: abcnews.go.com