We can all finally stop worrying about Hillary Clinton’s emails.

Last week, Congress received a brief, nine-page report from the State Department, which summarizes the department’s investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a personal email account to conduct work business while she was secretary of state. The report can be fairly summarized in two sentences: She shouldn’t have done that. But it wasn’t that big of a deal.

Thus, America finally has closure on a minor scandal that many of the nation’s most powerful and influential news editors treated as if it were the most important issue facing voters in the 2016 election. “In just six days,” according to an analysis of 2016 coverage published in the Columbia Journalism Review (CJR), “the New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.” And the Times was hardly alone in this regard.

By contrast, the Times’s piece on the State Department report concluding that Her Emails weren’t actually that big of a deal ran on page A16 in print. (It was featured somewhat more prominently on the Times’s online homepage.) Similarly, data provided to Vox by the liberal group Media Matters indicates that television news — all three major cable networks plus all three broadcast stations — spent a total of less than 56 minutes combined on the new State Department report.

The State Department’s report reaches two broad conclusions. Clinton’s “use of a private email system to conduct official business added an increased degree of risk” that classified information would be compromised. But “there was no persuasive evidence of systemic, deliberate mishandling of classified information.”

In 2016, the State Department’s inspector general also determined that Clinton’s Republican predecessors, Secretaries Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice, also received classified information on their personal email accounts.

So Clinton committed the same mistake committed by her predecessors — Powell reportedly advised Clinton to use a personal email account for non-classified communications shortly after Clinton became secretary — and the State Department’s report found no systemic mishandling of information.

Clinton’s use of private email was the sort of minor scandal that the public deserved to be informed about at some point during the 2016 election — after which the news cycle could move on to other, more important stories. But that sure as hell wasn’t how it was covered. Indeed, it is likely that Donald Trump is president today in part because of the press’s obsession with this very small story.

The press covered Clinton’s emails with an Ahab-like obsession

Months after the 2016 election, a team of researchers at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society set out to quantify which issues received coverage — and which issues were ignored — by major media outlets during that election. To do so, they read thousands of campaign-related articles in several major outlets, and counted how many sentences were devoted to various issues. The results are striking.

As CJR later summarized this research, the Berkman Klein Center “found roughly four times as many Clinton-related sentences that described scandals as opposed to policies, whereas Trump-related sentences were one-and-a-half times as likely to be about policy as scandal.” Indeed, emails so dominated coverage that “the various Clinton-related email scandals—her use of a private email server while secretary of state, as well as the DNC and John Podesta hacks—accounted for more sentences than all of Trump’s scandals combined (65,000 vs. 40,000) and more than twice as many as were devoted to all of her policy positions.”

Meanwhile, CJR researchers Duncan J. Watts and David M. Rothschild did a deep dive into how the New York Times covered 2016, and their findings are just as stark. “Of the 1,433 articles that mentioned Trump or Clinton,” during the last 69 days of the 2016 campaign, “291 were devoted to scandals or other personal matters while only 70 mentioned policy, and of these only 60 mentioned any details of either candidate’s positions.”

One-hundred fifty of these New York Times articles, moreover, appeared on the paper’s front page. Of these, only 16 discussed policy in any way, “of which six had no details, four provided details on Trump’s policy only, one on Clinton’s policy only, and five made some comparison between the two candidates’ policies.” By contrast, the Times ran 10 front-page articles on Clinton’s emails in just six days, between October 29 and November 3.

The overarching impression created by this reporting, in other words, was that the emails were more important than all of the policy questions facing voters in 2016 — questions like whether millions of Americans would lose health care, whether the United States would bar immigrants because of their religion, and who would control the Supreme Court.

We cannot know with certainty what would have happened if news outlets did not fixate on this story during 2016. But as Tina Nguyen wrote in Vanity Fair, “you could fit all the voters who cost Clinton the election in a mid-sized football stadium.” As FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver wrote in 2017, “Hillary Clinton would probably be president if FBI Director James Comey had not sent a letter to Congress on Oct. 28” that reinvigorated the emails story shortly before the election.

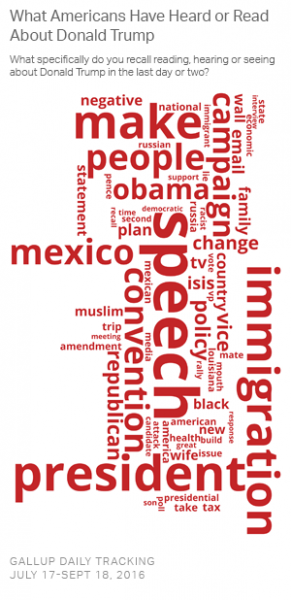

We do know, moreover, that the obsessive coverage of Clinton’s emails shaped how voters perceived the 2016 race. In September 2016, Gallup asked voters what they recalled hearing about the two major presidential candidates. The word cloud for Trump primarily shows a mixture of immigration policy and generic campaign terms.

Meanwhile, Clinton’s word cloud speaks for itself.

The press obsession with government IT security, moreover, appears to be a passing fad that ended the moment Clinton lost her shot at the White House. News broke last November, for example, that First Daughter and presidential aide Ivanka Trump “sent hundreds of emails last year to White House aides, Cabinet officials and her assistants using a personal account, many of them in violation of federal records rules.” Yet this story received only a fraction of the coverage that Clinton’s emails received.

There is an important conversation to be had about email security at the State Department, but we didn’t have it in 2016

Setting aside the media mania over Clinton’s emails, there is a very important story about classified email security at the State Department that journalists could have told in 2016. Broadly speaking, the federal government’s processes regarding how classified information should be handled are designed with low and mid-level personnel in mind, and are ill-suited for the issues facing very senior diplomats.

As of October of 2015, 4.3 million people have security clearances from the United States government. This includes some very low-level personnel who have access to extraordinarily sensitive information. Think of Chelsea Manning, the former Army intelligence analyst who leaked hundreds of thousands of diplomatic cables, battlefield reports, and other classified documents when she was a junior enlisted soldier.

Because there is such a high risk that someone could leak damaging national security information, the protocols for handling such information are often very strict, and the penalties for violating these protocols can be quite high. The fact that so many people must comply with these protocols also fed a perception that Clinton refused to obey rules that rank-and-file government employees must follow religiously.

But the fact is that the secretary of state — be it Clinton, Rice, or Powell — is very different from a low-ranking soldier like Manning. The rigid protocols that we impose on most people with security clearances do not always make sense for senior diplomats.

As Suzanne Nossel, a former deputy assistant secretary of state under Clinton, explained in a 2015 piece in Foreign Policy, “neither then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton nor her aides had a classified smartphone.” Typically, State Department officials with access to classified information will have one email address for ordinary communications and another for classified communications (Clinton used her personal address as her address for ordinary communications). But, to access the classified address, an official must be at a special computer set up to access classified information. Because high-level officials are not always near such a computer, an email sent to a classified address may not be seen for “hours or even days.”

A senior diplomat might need the secretary to tell her how to vote on a particular United Nations resolution, for example. But if that diplomat follows proper protocol and queries the secretary over the classified email system, the secretary may not see the email until the vote has already taken place.

Senior diplomats, in Nossel’s words, must “make tough choices about the trade-off between security and the need for timely transmission of vital information.” And in the heat of an ongoing negotiation or an impending crisis, it is not always clear that following rigid protocols is in the best interests of the nation.

Clinton was, of course, the head of the State Department, so she fairly can be criticized for not implementing new processes that could address these concerns. There is a nuanced conversation to be had about how the State Department should balance concerns about information security with senior diplomats’ need to convey information quickly. News outlets could have used the controversy over Clinton’s emails as a jumping-off point to spark this conversation. Perhaps this kind of coverage could have pushed the department to implement needed reforms.

Instead, we got a circus where every new twist in the emails saga received big headlines and overwhelming coverage. We got an election cycle where Hillary Clinton’s IT practices received more coverage than her opponent bragging about how he grabs women “by the pussy” without their consent.

And now we have an appropriate bookend for this media-made scandal: a State Department report that finds it was no big deal in the end, published on page A16 of the New York Times.

Sourse: vox.com