November 20, 2018

To Whom It May Concern:

Sitting at my desk in the fall of 2018, I have no way of knowing what the future holds for the United States under the administration of Donald Trump. I hope it will all turn out for the best. But I fear that it will not.

The election of a man temperamentally unfit for the presidency and lacking in the basic qualifications to perform the job, backed up by congressional allies who seem determined to ignore his flagrant corruption, is still an alarming situation. The odds that he will systematically corrupt American institutions and install an authoritarian kleptocracy or blunder into some kind of catastrophic war seem simply too high to entirely discount.

And if something big and awful does happen, I know from my own reading of history that the scholars of the future will be sorely tempted to look for causes that are big in proportion to the consequences.

Historians will write of a growing trend toward partisan polarization and a brewing sense of political crisis dating back to Bill Clinton’s impeachment in 1998. They’ll note the projected end of America’s white majority, the geopolitical revolution induced by Russia’s reinvention of itself as an international beacon of cultural conservatism, and the corrosive effect of the 2007-’08 financial crisis. The “failures of neoliberalism” will come in for scrutiny.

All true and all important. But my message to the future is this. No matter how stupid it sounds, and no matter how much political and journalistic elites on all sides of America’s toxic politics began trying to ignore it as soon as the votes were counted, the dominant issue of the 2016 campaign was email server management.

What the email story was

Back in the early days of the 21st century, it was common for people to communicate via an open protocol known as email that was developed originally in the 20th century before internet access became widespread. Most email users had a “personal” email account but were also issued a “work” email account associated with their specific job. A typical personal email account would be obtained for free from an ad-supported service such as Google, Yahoo, AOL, or Microsoft. But because Bill Clinton found himself in the unusual employment circumstances of being an ex-president in 2001, he hired someone to set up a private server for himself and his wife, and her personal email was hosted on that server.

At the time Clinton became secretary of state, she was a heavy user of a once-popular early smartphone line called BlackBerry.

The state of federal government information technology infrastructure, at the time, was such that a work-issued email address could only be associated with a work-issued BlackBerry and the work-issued BlackBerry could not be connected to a personal email address. Many federal workers at the time handled this by carrying around two smartphones, which was an annoying but workable solution. Clinton, as the boss, chose to spare herself the inconvenience involved by simply ignoring State Department guidelines and using her own phone and her personal email address.

This came to light some years later and sparked a politically motivated investigation into whether the use of personal email account violated not only State Department IT guidelines but also federal law regarding the handling of classified information. To convict someone under the relevant statutes, prosecutors have to show malign intent, which was pretty clearly not present, even though it turned out that some of Clinton’s email traffic did contain classified information. For this reason, FBI Director James Comey told the American people that “no reasonable prosecutor” would bring a case against Clinton.

The email story dominated the campaign

If that sounds far too boring and unimportant to have conceivably dominated the 2016 presidential campaign, then it is difficult to disagree with you. And yet the facts are what they are. Indeed, by September 2015 — more than a year before the voting — Washington Post political writer Chris Cillizza had already written at least 50 items about the email controversy.

Email fever reached its peak on two separate major occasions. One was when Comey closed the investigation. Instead of simply saying “we looked into it and there was no crime,” Comey sought to immunize himself from Clinton critics by breaking with standard procedure to offer extended negative commentary on Clinton’s behavior. He said she was “extremely careless.”

Comey then brought the email story back to the center of the campaign in late October by writing a letter to Congress indicating that the email case had been reopened due to new discoveries on Anthony Weiner’s laptop. It turned out that the new discoveries were an awfully flimsy basis for a subpoena, and the subpoena turned up nothing.

This all still sounds unimportant, but it was not at the time:

- The New York Times dedicated 100 percent of its above-the-fold space to coverage of Comey’s letter to Congress.

- Throughout the campaign season, network newscasts dedicated more time to Clinton’s email server stories than to stories about all policy issues combined.

- Donald Trump’s campaign rallies featured regular “lock her up” chants, centering the email server as the opposition’s main criticism of Clinton.

- Across five television networks and six major newspapers, 11 percent of campaign coverage was stories about Clinton’s email server.

Critically, one useful function of email-based criticism of Hillary Clinton was to pull together the Trumpian and establishment wings of the Republican Party. That’s why it served as the central theme of the 2016 Republican convention, allowing the likes of Scott Walker and Rick Perry to deliver on-message speeches rather than clashing with Trump’s message.

The email story made a big difference

Historians looking through the archives of stories published in November and December 2016 will find billions of words published on the nature of Trump’s appeal to voters who liked him. These takes, whether accurate or not, are important pieces of sociological exegesis that shed light on the nature of our political debates.

But in terms of what actually drove the election result, people who liked Trump were not the key decisions-makers. Not only did he lose the national popular vote, but even in crucial swing states he was mostly viewed negatively.

In Pennsylvania, for example:

- 56 percent of voters said Trump was unqualified to be president.

- 62 percent of voters said Trump lacked the right temperament to be president.

- 60 percent of voters said Trump was dishonest.

- 56 percent had an unfavorable view of Donald Trump.

At the same time, Barack Obama had a 51 percent job approval rating in the state. A majority of voters were okay with the incumbent administration, and a majority of voters took a dim view of Trump. But these marginal voters were also very skeptical of Clinton, and the email story that 65 percent of Pennsylvania voters said bothered them was a key reason.

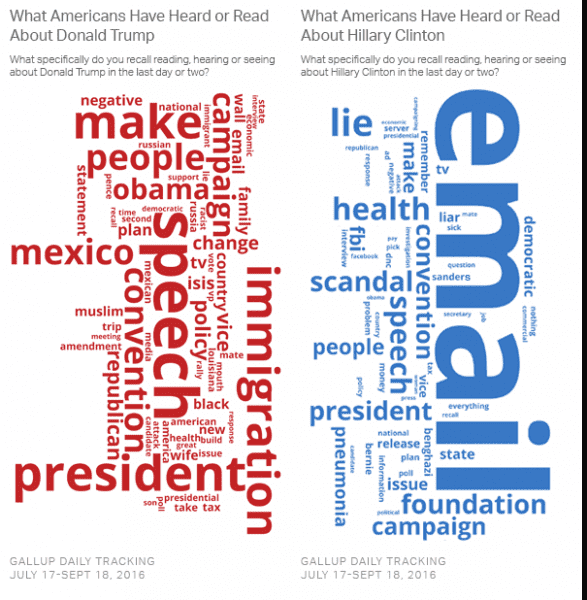

Indeed, research from Gallup indicates that emails dominated what voters heard about Clinton all throughout the campaign.

Research by Dan Hopkins of the University of Pennsylvania indicates that Trump dominated among voters who decided in the final two weeks of the campaign — a period in which Comey’s letters about Clinton’s emails dominated media coverage.

Big events sometimes have small causes

These events are at high risk of slipping out of view of the historical record for a variety of reasons. Republicans, for starters, had a vested interest in putting forward the idea that the election results constituted a sweeping public affirmation of their policy agenda. Competing factions of the Democratic Party, meanwhile, sought to use Clinton’s defeat as a rationale for advancing their own preferred substantive agendas.

More broadly, the further the email issue receded into the past, the less credible it seemed that a major historical turning point could really have hinged on something so trivial.

And certainly one can imagine a variety of scenarios in which Clinton might have won the election despite her email woes. More successful economic policymaking from the Obama administration could have done the trick. So could a better campaign message or better targeting of resources. It was, after all, a very close election.

The crucial point, however, is that in broad ideological terms, the 2016 election happened at a time when the incumbent president was popular and the insurgent demagogue promising dramatic change was not popular. The unpopular insurgent managed to win, despite accumulating fewer voters than the popular incumbent’s designated successor, largely because she had become personally unpopular thanks to a massive onslaught of criticism largely focused on her email server.

Even at the time, some of us found it hardly credible that a decision as weighty as who should be president was being decided on the basis of something as trivial as which email address the secretary of state used. Future generations must find it even harder to believe. But the facts are what they are — email server management, rather than any deeper or more profound root cause, was the dominant issue in Donald Trump’s successful rise to power.

Sourse: vox.com