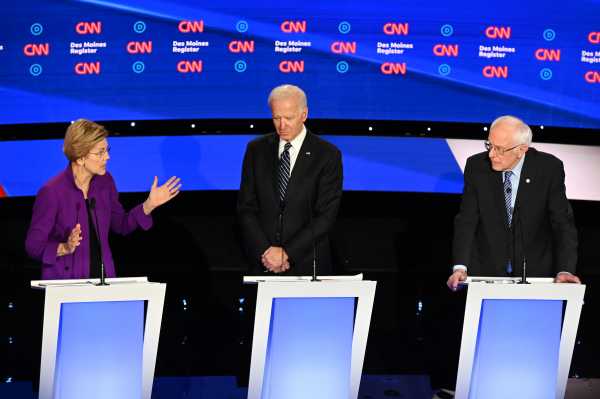

One of the most discussed moments at Tuesday’s seventh Democratic primary debate happened after it was over, when Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders met for a post-debate discussion.

Sanders appeared to extend his hand for a handshake as Warren walked over, but no handshake took place.

Many viewers on social media — and post-debate analysts — described the moment as a snub, with Warren refusing to shake Sanders’s hand.

Perhaps it was an intentional snub and Warren didn’t want to shake his hand. It could also have been an awkward oversight akin to not noticing someone trying to give you a high-five or waving to someone only to realize they weren’t waving at you. It’s even less clear what they discussed.

Nevertheless, CNN’s post-debate commentary featured a lengthy discussion of the moment, and online Sanders supporters attacked Warren, calling her names and declaring themselves members of a new #NeverWarren movement.

In some ways, all the attention heaped on this one moment was unsurprising, coming after several days of escalating tension between the two progressive leaders — all while the Iowa caucuses that are effectively any of the top four candidates’ to take loom.

But it also is an example of a media — and human — tendency to allow the minor to obscure the major. Making a handshake the biggest moment of January’s debate has drawn attention away from important things that informed it: narrowly, Sanders and Warren working hard to bury the hatchet in the name of advancing the progressivism they share, and broadly, conversations around the sexism inherent to questions of whether a woman can be president.

Why everyone was so interested in the Liz-Bernie dynamic, briefly explained

Reading the post-debate exchange as a snub stems largely from a point of tension that emerged between the senators’ campaigns ahead of the debate. Warren and Sanders have had a nonaggression pact throughout the campaign, but that truce was broken following a report from Politico’s Alex Thompson and Holly Otterbein that the Sanders campaign had given volunteers a script that attacked other candidates, including Warren.

The Warren campaign responded to this by saying Sanders told Warren during a private meeting that he didn’t think a woman could win the White House in 2020. Sanders and his surrogates said the Vermont senator said no such thing. Warren and her surrogates said he did.

The issue came to a head on the debate stage, with each candidate sticking to their side of the story. And they appeared to have settled the issue, with both using a question about the disagreement to boost their candidacies and champion their support of women candidates: Sanders argued he’d waited to launch his candidacy in 2016 out of respect for Warren in case she wanted to run; Warren pointed out that the women on the stage had far better electoral records — particularly when facing populist Republicans — than the men.

In so answering, the progressives seemed to lay to rest an issue that threatened to distract from their pitches to voters weeks before the Iowa caucuses and that — given the rancor the disagreement inspired online — seemed poised to pettily divide progressives at a moment at which they are struggling to defend against the national popularity of moderate Joe Biden.

But the peace and goodwill engendered by the debate itself was largely derailed — among the senators’ bases, at least — by the moment CNN captured after, when no handshake occurred.

It is important to remember, however, that while everyone saw the same thing, we don’t actually know what happened.

We also have little idea what was said in the conversation that followed. The only information we have about the chat comes from entrepreneur Tom Steyer, who moved away to give the senators space to talk. Steyer told CNN the two lawmakers were discussing “getting together.” But that could mean anything, from a meeting to squash the beef once and for all to a double brunch date. And the conversation could have gone anywhere from there.

Obviously, this little moment is getting so much attention because the Iowa caucuses are now about two weeks away. Voting in New Hampshire comes directly after that, then contests in Nevada and South Carolina. In other words, time is running out.

Candidates are under enormous pressure to differentiate themselves and to win over undecided voters. And their supporters, particularly those who have put in countless volunteer hours, are under just as much strain.

But in a rush to cast their particular candidate as the one true good — and some members of the media’s desire to add fuel to a potent narrative — we have become distracted from what is really important about the moment: that it is rooted in very real concerns over whether a woman can be president, and a sexism that lies at the heart of those concerns that very much needs to be addressed.

Democrats need to overcome doubts about the viability of women candidates

Concerns about the viability of a woman candidate were prevalent when Hillary Clinton challenged Donald Trump in 2016 and have not been resolved since.

“There’s a sense that there was backlash about the Obama presidency, and Hillary Clinton didn’t win,” Debbie Walsh, director of the Rutgers Center, told the New York Times. “So the conventional wisdom, which starts to feed on itself, is, ‘Well, we’d better just elect the thing we’ve always had,’ which is white men.”

That hesitancy is reflected in polls on the issue, many of which show that individuals want — or at the very least have no problem with — a woman nominee, but that they don’t believe other voters feel the same.

For instance, a July Daily Beast/Ipsos national poll found 74 percent of voters said they’d be comfortable with a woman as president, but only 33 percent said their neighbors would be fine with that. More broadly, this dynamic has been framed in terms of “electability” — more than anything, voters tell pollsters, they want a Democratic nominee who can beat Donald Trump.

It’s a conversation the candidates onstage were ready to wade into.

“Back in the 1960s, people asked could a Catholic could win. Back in 2008, people asked if an African American could win,” Warren said. “In both times, the Democratic Party stepped up and said yes, got behind their candidate, and we changed America. That is who we are.”

And Sen. Amy Klobuchar has routinely made the case she is the candidate with the most electability based on her record: She has never lost an election, and she performs well in traditionally Republican districts in her home state of Minnesota. She has also outperformed both President Barack Obama and Clinton. In 2012, when Obama carried Minnesota with 53 percent of the vote, Klobuchar got 65 percent in her Senate bid. Clinton won only nine of Minnesota’s counties in 2016; in 2018, Klobuchar won 51.

She also pointed to the victories women have had over Republicans in recent years, beyond the wins she and Warren accomplished, saying Tuesday, “When you look at the facts, Michigan has a woman governor right now and she beat a Republican, Gretchen Whitmer. Kansas has a woman governor right now and she beat Kris Kobach.”

As Vox’s Li Zhou noted, “Women also flipped the lion’s share of House seats that Democrats retook in 2018, as well as both Senate seats — and research has long shown that women candidates win at the same rate as men when they run for elected office.”

But that — and Klobuchar’s other arguments — haven’t swayed voters in favor of the Minnesota senator. Instead, Biden, who has lost elections, and who does not have as strong a record of winning in Republican areas, is seen as Democrats’ best chance to beat Trump, according to recent polls. And it is Biden who leads nationally.

Christina Reynolds, a spokesperson for Emily’s List, told Vox this dynamic reflects what the term “electability” actually means: “Metrics like authenticity and likability and electability are just code that we use against candidates who are not like what we are used to.”

Or as Zhou has explained, “The expectation of who can win is inextricably wrapped up in the knowledge of who has won.”

In 2020, anything could happen: Trump enjoys the advantages of incumbency and the Electoral College system, but experts have said the Democratic base is incredibly energized and is expected to show a strong turnout. Respondents to polls may believe Biden has the best chance against Trump, but experts have told Vox that no research argues a woman would be destined to lose in November because of her gender.

Democrats need to face these facts, but they also need to understand and work to undo the thinking that causes voters to pause when it comes to caucusing or voting for a woman.

Instead, they’re debating whether one candidate snubbed another’s proffered hand.

Sourse: vox.com