It doesn’t require a lot of digging to wonder whether the laissez-faire, free market mantra of the past several decades has worked out as promised: Stock prices and corporate profits have far outpaced wage growth in the United States; lax antitrust enforcement has set the path toward enormous amounts of corporate concentration, often to the detriment of American consumers; inequality is a central fact of American society.

But if neoliberalism is failing, is there a vision to replace it? Specifically, a progressive vision coming from the left? A new set of papers says yes.

On Wednesday, the progressive think tank the Roosevelt Institute released a pair of papers examining the shortcomings of neoliberalism and mapping out an emerging progressive worldview for what comes next. Laying out the left’s emerging ideas on everything from taxes and government debt to antitrust policy, unions, and industrial policy, the papers create a who’s who and what’s what in progressive economic thinking. Their overarching theory: It’s time to reject not only the conservative guiding principle that there is always a strict trade-off between redistribution and growth, but also the faith that many mainstream and moderate Democrats have had for the past several decades that efficient markets needed some regulations and redistribution but can largely take care of themselves.

Instead, it’s time for a broad-based, democratic effort for the government to shape the economy and foster the public good.

“All of the critiques actually imply a set of real solutions, so it’s not just, yes, a lot of people see that inequality’s getting worse, and we have a lot of complaining about it and can identify the problems,” Felicia Wong, president and CEO of the Roosevelt Institute, told me. “Actually, what it suggests is there are a lot of policy solutions that we could actually put into practice and would not harm growth, would not harm economic health; in fact, we would strengthen the economy and make people’s everyday lives better.”

It’s a moment when there could be a shift in thinking, and perhaps even policies, on these issues in the US. The 2020 Democratic field is well to the left of the 2008 and 2016 cycles; the members of “the Squad” have introduced themselves as a cohort of high-profile progressive women in Congress; the Sunrise Movement is leading the charge on climate change.

The Roosevelt Institute doesn’t specifically lay out new research or concepts but instead puts progressive thinkers and institutions in conversation with one another and distills thousands of pages of research into a more digestible format. (The papers are fewer than 100 pages combined.) The result is a broad map of a potential leftward direction for government policy and enforcement — and a warning against continuing with the prevailing neoliberal thinking that has, in many cases, become the norm, or allowing the rise of right-wing populism that marries anti-corporate sentiment with white nationalism.

Efficient markets for whom?

The first plank of the Roosevelt Institute’s effort is an examination of neoliberalism and where it has — and, more prominently, hasn’t — worked.

Authored by Mike Konczal and Katy Milani, fellows at the think tank, and Ariel Evans, executive assistant to the Roosevelt Institute’s president and CEO, the paper looks at what free market thinking was supposed to deliver, and the actual results.

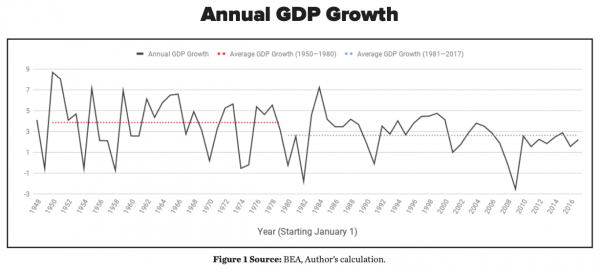

Here was the promise that many mainstream policymakers over the past 50 years bought: Lower corporate taxes, deregulation, and privatization will translate to economic growth — namely, a higher GDP. And they believed the inverse, too — that government intervention and overregulation will hold the economy back.

Within the Democratic Party, it hasn’t played out as dogmatic free market, libertarian thinking, but rather as an approach that tempers the market in some ways — some extra money for low-income people, environmental regulations, consumer-related guardrails — without, in the private sector’s view, overstepping. It still gives financial markets a leading role in shaping investments and corporate decisions, the idea being that the markets know best and will compete away problems and inefficiencies.

But a lot of research shows — and many Americans feel in their everyday lives — that’s not exactly how it’s worked out. Profit-seeking investors and corporations focused on profits above all else haven’t created the type of broad-based prosperity envisioned, according to the paper’s roundup of dozens of studies and pieces of research. Neoliberalism didn’t necessarily promise an equitable, fair society, but it was supposed to deliver GDP growth, and that hasn’t really happened. Different economists may have different theories on why the economy isn’t growing like it used to, but looking to the markets to deliver outsize growth doesn’t appear to have worked.

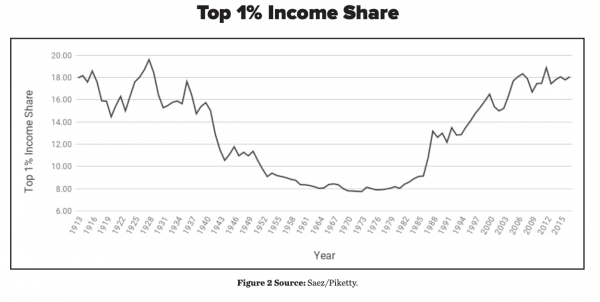

As for the other side of the coin? Evidence suggests that higher levels of redistribution don’t have a big impact on growth, at least not in extreme circumstances. But the belief that redistribution comes at the cost of growth has led to an increase in inequality. As the paper’s authors note, research from economists Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty shows that the share of income of the top 1 percent grew from 8 percent of total income in 1979 to 18 percent in 2017.

Wage growth has slowed, economic mobility rates have worsened, and people who start at the bottom are not more easily able to move up. Lots of people are still waiting for tax cuts given to those at the top to trickle down. It turns out lax antitrust enforcement doesn’t increase competition and innovation — just ask yourself how many options you have for internet providers in your neighborhood, or the last time you had an array of good, affordable options to book a flight.

The authors also point to the deregulation of the financial sector, which has translated to growth and profits for the industry but not a better scenario for everyday Americans. And shareholder primacy (where corporate boards prioritize maximizing shareholder returns over other stakeholders, such as workers and communities) has led to short-termism that can sometimes hamper a focus on long-term investment and growth.

Free market thinking has fallen short when it comes to racial inclusion and equality. As the theory goes, unbiased employers, consumers, and producers get a competitive advantage by dealing with people of color and women, so market competition would compete away wage gaps and wealth disparities. But, again, that’s not how it’s gone:

Mapping out a new progressive view of the world

The Roosevelt Institute examined work from more than 150 thinkers in order to distill a new progressive vision for the United States. There’s no one set answer. But instead of a world where capital returns will always outpace wage gains, the progressive worldview puts in place higher taxation. It focuses on robust antitrust enforcement instead of allowing for corporate concentration, puts power back into the hands of organized labor, and ensures women and people of color are included.

“This isn’t just a flash in the pan — this is really based on a lot of work by a lot of preeminent scholars and thinkers and policy experts,” Wong, who authored the paper outlining the positive vision for a progressive worldview, said.

She identified the various critiques of neoliberalism that are embedded with positive progressive solutions and distilled them into four groups. It’s not a cohesive progressive answer, but instead a set of four broad categories of answers, many of which work in concert.

- New structuralists: The theory at the center of the “new structuralist” belief system is that government rules structure markets, and a new set of rules is needed to foster more equality and widely shared prosperity. A major plank of this is tied to antitrust enforcement and a government that prevents a wider range of merger types and considers a broader set of stakeholders when deciding whether to approve a deal. It also entails higher taxes on the rich and corporations, and measures such as a potential financial transaction tax; it also puts limits on corporate governance matters, such as stock buybacks.

- Public providers: The “public providers” advance the idea that the government should provide essential goods and services instead of leaving it up to private actors. They promote more public spending and government involvement in arenas such as child care and paid family leave, as well as guaranteed health insurance, broadband access, and access to jobs. The basic theory is that the government can be more efficient at providing certain public goods, not less, and that concerns about the public debt have been overblown. There’s a specific focus on public provisions that correct for racial and gender discrimination.

- Economic transformers: The economic transformers call for a greater government role in directing the economy so that it produces better outcomes for people and the planet, and also makes sure that wide swaths of the population aren’t left behind amid technological change and globalization. The paper points to the Green New Deal as a prime example of the approach: a public-investment-led initiative that employs different policy tools to promote innovation, equity, jobs, and decarbonization.

- Economic democratists: Implementing the types of policies being proposed in progressive circles isn’t going to happen overnight, or without some real electoral and institutional shifts first. That’s where the economic democratists come in. They argue that economic reform hinges on participatory democracy, where unions are strengthened, communities are activated, and public agencies are open and transparent.

At the center of the thinking among the four groups are some identifiable themes: Markets are structured by choices and by power, whether in public or private hands, and policy choices make a difference. But as Wong notes in the paper, there are also tensions: There’s still a debate to be had over whether authority should be more localized or more centralized, and how heavily we should lean on expertise in designing policies and making decisions. The papers are meant to serve as a tool to organize the conversation and, hopefully, connect these big structural issues to people’s everyday lives.

“It’s not just about my struggle, it’s not just about my attempt to find day care, but we need a system that can provide these things, and by the way that’s possible, but it’s only possible if we see these problems as systematic,” Wong said.

There could be a return to normalcy — or an economic populism that ignores race

The papers’ authors believe that now is a moment for the way we think about the economy to move to the left. Progressive Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are among the leading candidates in the 2020 polls, running on ideas such as a wealth tax, universal health care, free public college, and the Green New Deal.

But a rejection of neoliberal thinking isn’t just developing on the left — there’s also a growing strain of it on the right. It’s evident in the appeal of President Donald Trump’s calls to “drain the swamp” (even as he’s filling it). It’s also evidenced in freshman Sen. Josh Hawley’s (R-MO) attacks on corporate power and big tech and conservative pundit Tucker Carlson’s assailing of the “ruling class” and moneyed interests.

Many progressives acknowledge that there is some overlap with figures such as Hawley and Carlson in their economic thinking. However, they emphasize that the views of some on the far right are also aligned with white nationalism and a belief in a sort of welfare state for white people. And the type of vision the left promotes is one that specifically addresses racial and gender inequality. From Wong’s paper:

“One version of the post-neoliberal future is anti-corporate, but it’s also white nationalist and racially exclusionary,” Wong said.

She also warned of the risk of returning to normalcy — for which, in the era of Trump, there is a deep desire among many Americans. It’s the difference between the type of promise former Vice President Joe Biden makes versus Sanders and Warren, a world where Americans can return to not paying attention to what’s going on in government compared to a world that necessitates mass action and pressure to implement big, structural change.

By the progressive worldview’s assessment, inequality is too problematic and monopoly power too destructive to return to the efficient markets, hands-off approach. “Basically, the current system is vacuuming too many resources to the top, so even if you’re going back to normal with respect to how we do politics, there is no going backward, there is no normal that is going to solve our problems,” Wong said.

Sourse: vox.com