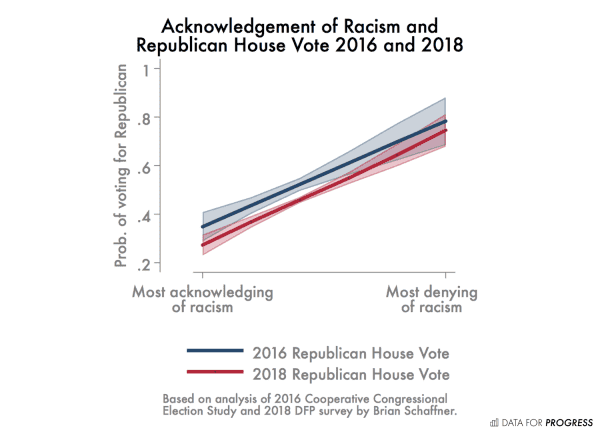

It sometimes feels like there’s nothing new to be said on the tedious topic of the role of racism in American politics, but Brian Schaffner a political scientist at Tufts offers this chart in a post for Data for Progress that really does shed a lot of light:

He looks at the correlation between voting for Republicans and people’s score on an index academics call “denial of racism” versus “acceptance of racism.” People who score high on acceptance of racism (people like me) think that anti-black prejudice plays a large role in structuring American life and explains lots of important features of American society.

People who score high on denial of racism think this is bunk, and see black people who complain about racism as “playing the race card.” Meanwhile, acceptors of racism see denial of racism as itself a manifestation of racism.

Deniers of racism see it — if it exists at all — as a matter of individual animus with little structural impact on American life. A racism-denier is likely to argue that they can’t possibly be racist because they have one black friend or enjoyed seeing Ben Carson speak on the campaign trail, and were thrilled when Kanye West said nice things about President Donald Trump.

The chart says two things about this:

Point one means that racial attitudes do a lot, in a statistical sense, to predict who votes for Republican candidates. If you do a similar correlation for measures of economic well-being, you’ll see a much weaker correlation. This is what people mean when they say that racism rather than economic anxiety explains Republican wins — views on race are an incredible driver of voting behavior, and if everyone was super-woke the GOP would get crushed.

But point two means that the difference between the election Democrats lost in 2016 and the election Democrats won in 2018 had nothing to do with race. There was no great “awokening” that led voters to reject the GOP.

Rather, super-woke people became even less likely to vote Republican than they were two years ago, and non-woke people also became less likely to vote Republican. In both years, Democrats’ base was among the racism-acceptors, and they struggled with the racism-deniers. But what made the difference in 2018 was just that they did better with everyone, regardless of their racial views.

The upshot of this is that statistical analysis of past voting behavior tells you relatively little about what will work to win elections in the future. The observation that racial views are a strong driver of voting behavior is true and important to understand. But the difference between winning and losing can just be that you come up with something else to say that people generally like better than what you said before. That new, better message won’t necessarily break the link between racial views and voting — but it doesn’t have to do that in order to work.

Sourse: vox.com