In Africa, there are two kinds of elephants: savanna and forest elephants. The species diverged somewhere between two and six million years ago, with the better-known savanna elephants spreading over the plains and open woodlands of Eastern, Southern, and Western Africa while forest elephants stayed behind in the dense forests at the center of the continent. Although the two occasionally hybridize, they are widely viewed as separate species. Forest elephants are smaller, with smaller and straighter tusks. The size of their tusks, however, has not protected them from rampant poaching, because the tusks have a distinctive hue, sometimes known as “pink ivory,” that has made them particularly valuable.

Something about the nobility of forest elephants regularly raises concern for their extinction. The tropical forests of the Congo Basin, once considered impenetrable, are now yielding to logging roads, mines, and even palm-oil plantations. In 2013, a widely respected study by Fiona Maisels, of the Wildlife Conservation Society, found that, between 2002 and 2011, the population of forest elephants had declined by sixty-two per cent. Perhaps as few as eighty thousand remain. The story of these declining numbers is also a story of habitat destruction. Where forest elephants exist in an undisturbed state, they build networks of trails through the deep forest. These trails connect mineral deposits, fruit groves, and other essentials of forest-elephant life. In Central Africa, there are dozens of fruit trees whose seeds are too large to pass through the guts of any other animal and for which forest elephants have evolved as the sole dispersers. These trees line the forest-elephant paths. Where elephant populations are disturbed, the paths disappear.

Matt Davis, a researcher in ecoinformatics and biodiversity at Aarhus University, in Denmark, recently published a paper arguing that we are entering a period of extinction of large mammals akin to the scale of the extinction of the dinosaurs. “We are now living in a world without giants,” he told the Guardian, and went on to detail the many ecological consequences of the loss of megafauna. When I asked John Poulsen, an assistant professor of tropical ecology at Duke’s Nicholas School of the Environment, if this observation could apply to the role of forest elephants, he said, “Absolutely.”

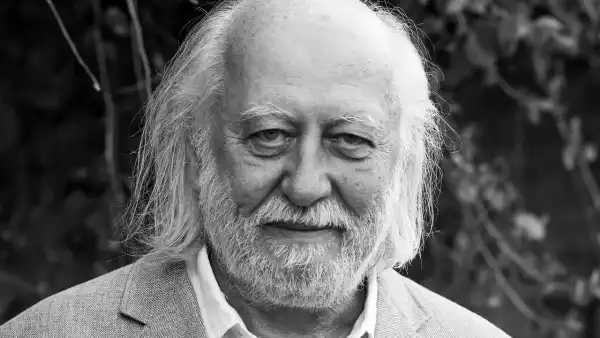

The sculptor Todd McGrain has made a name for himself, over a thirty-year career, as the creator of sculptural monuments to birds that have been the victims of “human-caused extinction.” It’s not, therefore, entirely surprising that he has directed a documentary about forest elephants, “Elephant Path / Njaia Njoku,” showing at New York’s DOC NYC film festival this Wednesday and Thursday. McGrain’s subjects have included, among others, the passenger pigeon, the great auk, the Labrador duck, the heath hen, and the Carolina parakeet. When McGrain was the artist in residence at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Katy Payne, founder of the Elephant Listening Project at the Bioacoustics Research Program, introduced him to something she had discovered: forest-elephant infrasound, which is how elephants communicate inside the forest, at a frequency too low for human ears to register. She pitched up the recordings of elephant calls so that McGrain could listen to them. “I couldn’t help but hear them as bird calls,” he told me. “It was the complexity of their language that grabbed me.”

McGrain was also reminded of the dialogue surrounding the extinct bird species he’d worked with. “I was always coming across the voices of people who’d raised the alarm about imminent extinctions,” he said. “These voices affected me deeply. I realized, listening to the vocalizations of forest elephants, that I could be one of those people.”

From Katy Payne, McGrain learned of Andrea Turkalo, an elephant behavioral biologist who, for more than twenty years, had been working in Dzanga bai, a remote forest clearing in the Central African Republic. Forest elephants congregate in Dzanga bai in unparalleled numbers. Turkalo, who I wrote about in 2015, has been pretty much the only person working to learn about the family and social structures of forest elephants. Turkalo avoids using computers for identification because she wants to train her eye to better understand the elephants she studies. “When I go to the bai and if I don’t know a new elephant,” she said in the film, “I draw its ears, but, after a while, you begin looking at elephants the way you do people. They have faces.”

McGrain was determined to make Turkalo the subject of a film, but, by the time he had secured funding and a crew and had gotten Turkalo to sign on, the politics of the region intervened. In March of 2013, there was a coup in the Central African Republic. Insurgents, including a large group of Janjaweed from nearby Darfur, overran Bangui, the capital, and soon descended on Turkalo’s site, killing twenty-six of her study elephants and hacking off their tusks. By the time McGrain arrived a month later, Turkalo had already fled, insurgents had occupied the region, and the bai was littered with elephant carcasses.

The absence of Turkalo had a surprise benefit, however, because it put McGrain in touch with one of Turkalo’s trackers, a Bayaka pygmy named Sessley. (“White people have come here, and I work with them all,” Sessley says in McGrain’s film. And “when the work is done, they go back to their own countries. The only one who has stayed is Andrea.”) The Bayaka are semi-nomadic forest people. They hunt with homemade crossbows, spears, and nets woven from forest vines. They scale tall trees and converse with forest animals. Some years ago, the geneticist Douglas Wallace observed that the Bayaka were closer in their genetic composition to the original modern humans, who left the continent fifty-or-so thousand years ago, than all but a handful of other populations in Africa.

During the insurgent occupation, Sessley and other Bayaka fled to the forests around Bayanga and camped there, away from the turmoil. McGrain wound up spending time in the forest with Sessley during several of his subsequent filming trips to the Central African Republic. On one occasion, Sessley took him to the Sessley River, for which he was named and along which he was born. “I feel the presence of my mother and father here,” he tells McGrain. “This is where I took my first drink of water and took my first bath.”

McGrain told me that the Bayaka’s knowledge of elephants was incredible. “We’d be walking in the forest and they’d stop and say, ‘We need to go another way, there are elephants ahead.’ I wouldn’t have seen or heard anything.” Sessley took McGrain along elephant paths and pointed out the fruit trees that the elephants had dispersed. “These are the banda seeds left by the elephants,” he tells McGrain on one such occasion. “Now the trees are growing here for all of us. We eat these things and the elephants eat them as well.”

When I wrote about Turkalo, one of her colleagues told me that the “basic biology” of forest elephants that Turkalo was working on would be what “scientists would need to try and rebuild a population.” This point became especially relevant when, in the aftermath of the Central African Republic civil war, the new government imposed an exorbitant set of research fees on Turkalo (who had returned a year after the coup), causing her to leave a second time. The first paper she published after leaving the bai was for the February 2017, issue of the Journal of Applied Ecology. In it, she argued that forest elephants were among the slowest reproducing mammals in the world and that it would take almost a century for them to recover from the poaching of the past decades.

Turkalo conducted her elephant studies from a viewing platform along one side of the bai, and in McGrain’s film she often sits there with Sessley, whom, she notes, feels that elephants are like people, because they interact with each other and have emotions. Sessley takes McGrain to see a skull from one of the elephants killed by the poachers, its tusks removed. “He was an old bull,” he says to McGrain. “He was important to this forest. Elephants like this one created this forest. Fools killed this elephant. Fools did this.”

Sourse: newyorker.com