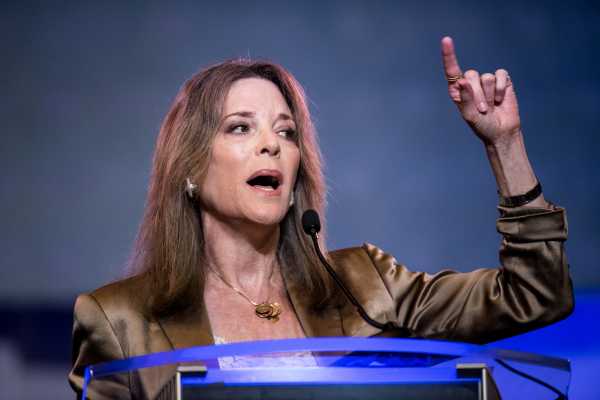

For many political observers and Twitter wags, Thursday night’s debate was the first introduction to Marianne Williamson’s curious mix of left-wing politics, difficult to place mid-Atlantic accent, and overt spiritualism. (Her final statement was a challenge to Donald Trump to “meet you on that field” where “love will win.”)

But while the memes and maybe-ironic praise flooding Twitter made clear that many viewers were encountering her for the first time, Williamson has been a familiar figure for those more likely to watch Oprah than Hardball since the 1990s, when her appearances on Winfrey’s show helped her ascend to become bestselling spiritualist with over a dozen books and legions of celebrity followers.

Williamson continually draws crowds in Iowa, where she’s moved. She made it on to the Democratic debate stage, unlike more experienced politicians like Rep. Seth Moulton and Montana Gov. Steve Bullock. And, like other presidential candidates, she can plausibly claim to represent a demographic swath of the public — and a growing one at that: Americans who are “spiritual but not religious.”

Data from the Pew Research Center shows that this group of Americans who describe themselves as spiritual and not religious, jumping from 19 percent of the population in 2012 to 27 percent in 2017. Like the Democratic electorate, they are more female than male and more likely to have attended college. More than half identify with or lean towards the Democratic Party, compared to 30 percent with Republicans. Similar data from the Public Religion Research Institute puts the spiritual but not religious group at 18 percent. (29 percent describe themselves as both spiritual and religious.)

Spiritually inflected practices and beliefs have suffused mainstream American culture, from the prevalence of yoga and meditation to the career transformation of Gwyneth Paltrow. Williamson herself is a testament to the fluidity of contemporary spiritualism.

She was raised in a Conservative Jewish home, but her first book is largely based on a 1976 work whose author said she had received Jesus’s dictation. In a column for Oprah.com promoting daily spiritual practice, Williamson was ecumenical, noting “there are many meditative practices, from Transcendental Meditation to completing the workbook A Course in Miracles to others that are rooted in traditions like the Christian, Jewish, Buddhist faiths and so forth.”

And Williamson’s policy stances — a version of Medicare-for-all, a Green New Deal, reparations — put her well within the Bernie Sanders-to-Kamala Harris left wing of the Democratic presidential candidates.

But she talks about them differently; when asked about prescription drug prices, she touched on a real policy issue — Medicare’s pricing policies for prescription drugs — but quickly pivoted away from having plans at all (“if you think we beat Donald Trump by just having all these plans, you’ve got another thing coming”) to a more, well, holistic criticism:

This type of rhetoric can easily go dangerous places, like her waffling on vaccines. But it can also speak to many people, including many women, who experience chronic ailments with unclear or unrecognized causes that are then poorly handled by the health care system.

From ignoring women in pain to misdiagnosing migraines and even endometriosis as something other than the often debilitating ailments they are, there is a demonstrably broad audience for whom this type of rhetoric could be appealing.

Williamson’s policy talk, laughable as it might have seemed last night at times, didn’t come from nowhere; it weaves together a familiar liberal critique of the health care system with a sense that our physical environment is a reflection of our degraded spiritual environment. It’s not Make America Great Again, but it diagnoses a similar feeling of emptiness and lost purpose and reframes it politically, but without the stigmatization and denigration of the already marginalized.

And who knows, maybe love will win — but first she’ll have to get to the field.

Sourse: vox.com