Joe Biden wants to see higher taxes on the rich, especially those who derive most of their income from stock ownership and other investments, according to a detailed revenue plan first reported this week by Bloomberg.

The former vice president’s overall vision for increasing social spending in the United States is ambitious — headlined by a $1.7 trillion climate plan, a $750 billion health plan, and a $750 billion education plan — but significantly less so than the ideas that left-wing rivals Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have put on the table.

His tax ideas, meanwhile, are less dramatic than the new wealth tax proposal Warren made famous — to say nothing of the even bigger wealth tax Sanders has proposed — often sounding more like tedious accounting details than visionary plans. They would roughly equal his $3.2 trillion in spending proposals over a decade, an order of magnitude less than what the left-wingers need to finance their Medicare-for-all plans.

But strikingly, even though Biden’s proposals on this front are much more moderate, they are almost identical in their orientation — raising money from a similar group of people for mostly similar reasons. Despite the disagreement about how far to go, all Democrats these days are basically reading from the same playbook, one that says Reagan-era conventional wisdom about the relationship between taxes and growth is wrong.

Consequently, if Biden’s plans were enacted, taxes on capital owners would end up substantially higher than they were at the end of President Barack Obama’s tenure, even as taxes on the working and middle classes are lower.

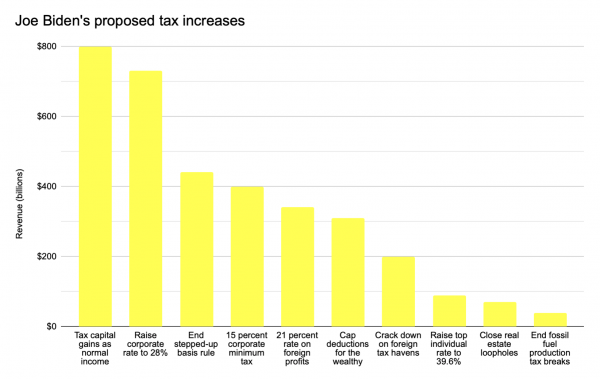

Joe Biden’s 10 tax increases

The Biden plan raises revenue in 10 ways, not really united by much of a conceptual theme other than a desire to primarily hit wealthy investors.

The most important of these, widely discussed by many Democrats in recent years, is ending the tax code’s practice of taxing capital gains and dividend income at a lower rate than ordinary labor income. Biden also wants to raise the corporate income tax rate from its current 21 percent to 28 percent — still lower than the 35 percent rate that existed pre-Trump, but Biden is keeping (and in some ways enhancing) many of the revenue-raising and loophole-closing measures that partially offset the cost of the Trump tax cut.

The third source of revenue is on the obscure topic of inheriting stocks and other investments. Capital gains taxes are levied on the profits realized at the time you sell a share of stock, so to the extent that Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos gets rich because Amazon stock gets more and more valuable, he doesn’t pay any tax on that as long as he holds the shares. The taxes come when he sells the shares and reaps the profits.

But if he passes shares on to his heirs as a gift, or when he dies and they sell the shares, the “cost basis” of the stock is “stepped-up” to the price at the time the shares were transferred. In other words, if you inherit stock and then immediately sell it, there are no taxable capital gains at all.

Biden would do away with this rule. He also wants to implement a version of what Warren has called a “real corporate profits tax” — preventing companies from reporting profits to investors while telling the IRS they have no taxable income. Biden’s version of this would levy a minimum tax of 15 percent on reported profits, even if deductions and credits push taxable profits down to zero.

Biden would also increase what is, essentially, the minimum tax rate on foreign income. The Trump tax bill created a rule known as the Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI) provision to try to discourage companies from shifting their profits to subsidiaries located in low-tax foreign jurisdictions. The current GILTI rate is a mild 10.5 percent, which Biden would double to 21 percent in the context of raising the corporate rate overall.

Biden is also reviving an Obama-era proposal to cap the value of all tax deductions at 28 percent, essentially eroding their value for rich people in the top tax bracket. He also wants to raise that top tax bracket rate back to its Obama-era level.

One of his campaign’s more interesting ideas — though not spelled out in detail — is that the United States should sanction foreign tax havens to get them to tighten up compliance, a measure they say could “conservatively” raise $200 billion over 10 years. In principle, it could raise a lot more than that, though of course the devil would be in the details in terms of what you actually did and how much change it generated.

Last are two small items: the perennial Democratic favorite of eliminating some tax deductions used by fossil fuel extraction companies, and a proposal to repeal a couple of tax provisions that are favorable to real estate investors like President Donald Trump.

Democrats are all heading in the same direction

This is all very different from the Sanders or Warren message in that it’s much less sweeping. At a fundraising event earlier in the cycle, Biden told donors that in his presidency rich people would need to pay more in taxes, but “no one’s standard of living would change. Nothing would fundamentally change.”

This plan more or less delivers on that promise. Rich people would pay higher taxes and, in the case of some very rich people, a lot more in taxes. And of course there are lots of millionaires and billionaires who would very much resist that kind of change.

But the vast majority of people would see no change at all, a huge difference from any Medicare-for-all plan which would involve broad taxes on employers at a minimum, and unlike in the Warren or Sanders plans, there’s no hint of the currently fashionable desire to liquidate billionaires as a class.

On another level, though, the various Democrats’ plans are striking in their similarity. The animating principle of most US tax policy since Ronald Reagan’s election has been the idea that taxes on investment income are very harmful to the economy. The idea is that you want to encourage financial investment because doing so leads to real investment in tangible things — office buildings, factories, business equipment, new inventions — that raise productivity, wages, and living standards.

The Obama administration backed off that consensus by including a “Medicare surtax” on investment income as part of paying for the Affordable Care Act. But later in his administration, Obama also proposed a number of other tax changes that would violate this consensus, including several that Biden is now touting, based on a range of newer work in economics that calls into question the link between investment taxation and growth.

Sanders and Warren go much further down this road than Biden or Obama. But really, whether you talk about a “wealth tax” or Biden’s 10-part plan or Sen. Ron Wyden’s idea to tax unrealized capital gains, everyone is positing that one can soak the ownership class without risking any broader harms to the economy.

Sourse: vox.com