Former Vice President Joe Biden on Tuesday unveiled a sweeping criminal justice reform plan — vowing to reduce incarceration, reform policing, and shift spending from incarceration to more social support for those at risk of crime.

The plan is one of the most comprehensive among the presidential campaigns, taking on various parts of the criminal justice system at once.

But it’s also an opportunity for Biden to repent for his “tough on crime” past after spending decades advocating for, writing, and passing legislation in the Senate that escalated mass incarceration and the war on drugs. In some ways, the plan specifically seeks to dismantle parts of Biden’s legacy — most notably, a sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses that contributed to racial disparities in federal imprisonment.

The plan includes many ambitious goals: decriminalize marijuana, eliminate mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent crimes, end the death penalty, abolish private prisons, get rid of cash bail, and discourage the incarceration of children. All of it is aimed at reducing incarceration and fixing “the racial, gender, and income-based disparities in the system,” according to Biden’s campaign.

Biden would also create a new $20 billion grant program that encourages states to reduce incarceration and crime. And he’d direct the savings from less incarceration at the federal level, along with additional federal money, to boost spending on education (including universal pre-K), mental health care, addiction treatment, and other social services.

The plan comes as Democrats have put forward several proposals for overhauling the criminal justice system, including Sen. Amy Klobuchar’s and Sen. Cory Booker’s clemency reform plans and Sen. Kamala Harris’s marijuana reform proposal. The rise of Black Lives Matter and broader bipartisan push for criminal justice reform, which most Democrats support, have led Democratic candidates to take a more aggressive stance on the issue.

For Biden, though, the topic is of particular interest because his long record in the Senate goes against many of the preferences of today’s Democratic voters on criminal justice issues. As a member and head of the Senate Judiciary Committee, he wrote and was the key leader in passing policies that helped develop today’s punitive criminal justice system.

It’s made Biden a consistent target for criminal justice reformers for years, going back to his time in President Barack Obama’s administration.

“There’s a tendency now to talk about Joe Biden as the sort of affable if inappropriate uncle, as loudmouth and silly,” Naomi Murakawa, author of The First Civil Right: How Liberals Built Prison America, told the Marshall Project in 2015. “But he’s actually done really deeply disturbing, dangerous reforms that have made the criminal justice system more lethal and just bigger.”

For Biden, then, his criminal justice plan isn’t just a chance to line up with the preferences of most Democratic voters. It’s also an opportunity to try to make up for the mistakes of his past.

There are major questions about how effective Biden’s plan will be in reversing the war on drugs and mass incarceration, given that much of criminal justice policy is driven not at the federal level but at the state and local levels. But Biden’s plan, at least, is a genuinely decent start at reforming a system that has made the US the world’s leader in incarceration.

What Biden’s criminal justice reform plan does

Biden’s plan is quite comprehensive, and you can read it in full at his campaign’s website. But to get a sense of what Biden is trying to do, here are several notable pieces:

- A $20 billion grant program to encourage states to reduce incarceration and crime: Modeled after the Brennan Center for Justice’s proposal, this would encourage states to reduce their use of prison by pushing them to, for example, eliminate mandatory minimums for nonviolent crimes. As it stands, nearly 88 percent of prison inmates are held at the state level, so this is the biggest chance in Biden’s plan at having a really broad impact on overall levels of incarceration. (Although similar efforts have failed before, and there’s the question of what to do with people in for violent crimes, who make up the majority of state inmates.)

- Use the president’s clemency powers to reduce incarceration: The president has broad powers to pardon or reduce people’s prison sentences. Biden vows to use these powers, much like President Barack Obama did, to reduce “unduly long sentences” for nonviolent and drug offenses. But as Rachel Barkow, a New York University law professor and expert on clemency, noted on Twitter, this appears to be much narrower than what other candidates have proposed. Since clemency reform is one of the few steps Biden could take without Congress, that’s a major weakness in the proposal.

- Eliminate the death penalty: Biden would push for legislation that ends the death penalty at the federal level and encourages states to do the same.

- Reel back punitive drug laws: There are several ways that Biden seeks to accomplish this. He would move to end federal mandatory minimum sentences. He’d push to decriminalize marijuana use at the federal level and allow states to legalize marijuana without the threat of federal interference. He’d end the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine, which has fueled racial disparities in prison sentences. He’d direct people who use drugs to drug courts and treatment instead of incarceration.

- Reform the police: Biden commits $300 million to the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) program, which has historically had mixed success in reforming police departments but he argues was never properly funded. He’d also try to empower the US Department of Justice to hold police departments accountable for abuses — something that President Donald Trump’s administration has worked against. (But as with efforts to reduce incarceration, there’s a question just how effective federal interventions would be in these areas, given that most policing is done at the state and local levels.)

- Tackle various root causes of crime: Biden promises to boost spending on education, housing, mental health care, addiction treatment, after-school programs, and other social services. Some programs will be offered within prison and to the formerly incarcerated, too, to help with rehabilitation. The idea is to tackle what experts and activists characterize as the root causes of crime, which, if successfully addressed, should lead to less crime — and incarceration — in the long term.

The plan goes beyond these examples. But together, these provisions exemplify the kind of comprehensive approach that Biden is going for: one that tackles every major aspect of the criminal justice system in some form.

One big question for Biden’s plan is whether Congress would go along with any of this. There are some parts of Biden’s plan he could do on his own as president — most notably, clemency. But he’d need Congress’s approval for the majority of his proposals, from the $20 billion grant program to ending mandatory minimums to tackling the root causes of crime. Given that Congress took years to pass a fairly mild form of criminal justice reform with the First Step Act, it’s unclear if federal lawmakers are truly ready for more ambitious proposals.

Still, the plan indicates that Biden, at least, is ready to go bigger on criminal justice reform.

Biden has a long record of supporting “tough on crime” policies

Since he announced his run for president, Biden has been dogged by questions about his criminal justice record. Throughout decades in the Senate, Biden spent much of his time pushing for policies that led to more incarceration and a harsher war on drugs. Here are just a few examples:

- Comprehensive Control Act: This 1984 law, spearheaded by Biden and Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-SC), expanded federal drug trafficking penalties and civil asset forfeiture, which allows police to seize and absorb someone’s property — whether cash, cars, guns, or something else — without proving the person is guilty of a crime.

- Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986: This law, sponsored and partly written by Biden, ratcheted up penalties for drug crimes. It also created a big sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine; even though the drugs are pharmacologically similar, the law made it so someone would need to possess 100 times the amount of powder cocaine to be eligible for the same mandatory minimum sentence for crack. Since crack is more commonly used by black Americans, the sentencing disparity contributed to racial disparities in incarceration.

- Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988: This law, co-sponsored by Biden, strengthened prison sentences for drug possession, enhanced penalties for transporting drugs, and established the Office of National Drug Control Policy, which coordinates and leads federal anti-drug efforts.

- Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act: The 1994 law, partly written by Biden, imposed tougher sentences and increased funding for prisons, contributing to the growth of the US prison population from the 1990s through the 2000s — a trend that’s only begun to reverse in the past few years. It also included other measures, such as the Violence Against Women Act that helped crack down on domestic violence and rape, a 10-year ban on assault weapons, funding for firearm background checks, and grant programs for local and state police. (For more, read Vox’s explainer on the law.)

Biden was explicit about his “tough on crime” goals with these measures. In 1989, at the height of punitive anti-drug and mass incarceration politics, Biden even went on national television to criticize a plan from President George H.W. Bush to escalate the war on drugs. The plan, Biden said, didn’t go far enough.

“Quite frankly, the president’s plan is not tough enough, bold enough, or imaginative enough to meet the crisis at hand,” he said. He called not just for harsher punishments for drug dealers but to “hold every drug user accountable.” Bush’s plan, Biden added, “doesn’t include enough police officers to catch the violent thugs, not enough prosecutors to convict them, not enough judges to sentence them, and not enough prison cells to put them away for a long time” — a direct call for more incarceration.

Later on, when the 1994 crime law passed, Biden boasted that “the liberal wing of the Democratic Party” was for “60 new death penalties,” “70 enhanced penalties,” “100,000 cops,” and “125,000 new state prison cells.”

All of this reflected a broader movement in the Democratic Party to both address the growing issue of crime and overcome successful Republican attacks about how Democrats are “soft on crime.” This helps explain not just why Biden said and did all these things, but why Bill Clinton signed the 1994 crime law and ran on its “tough on crime” provisions — including his support for the “death penalty for drug kingpins” — during his reelection bid in 1996.

Biden has offered a mea culpa of sorts for some of his past, acknowledging that creating extra punitive penalties for crack was “a big mistake,” and supporting efforts to reel back those penalties. “I haven’t always been right,” Biden said earlier this year, speaking to criminal justice issues. “I know we haven’t always gotten things right, but I’ve always tried.”

Still, a big worry in the criminal justice reform space is what would happen if, say, the crime rate started to rise once again. If that were to happen, there could be pressure on lawmakers — and it’d at least be easier for them — to go back to “tough on crime” views, framing more aggressive policing and higher incarceration rates in a favorable way.

Given that the central progressive claim is that these policies are racist and, based on the research, ineffective for fighting crime in the first place, any potential for backsliding in this area once it becomes politically convenient is very alarming.

The concern, then, is what would happen if crime started to rise under President Biden: Would he fall back on old “tough on crime” instincts, calling for harsh prison sentences once again?

“[E]ven if Biden has subsequently learned the error of his ways,” Branko Marcetic wrote for Jacobin, “the rank cynicism and callousness involved in his two-decade-long championing of carceral policies should be more than enough to give anyone pause about his qualities as a leader, let alone a progressive one.”

At least so far, Biden’s plan doesn’t appear to have changed many minds. Booker, a presidential candidate who has focused on criminal justice reform in the Senate, responded to the plan with sharp criticism: “It’s not enough to tell us what you’re going to do for our communities, show us what you’ve done for the last 40 years. You created this system. We’ll dismantle it.”

Biden’s plan can only go so far

For all the concern about Biden’s record, it’s unclear how effective any president can be on criminal justice issues.

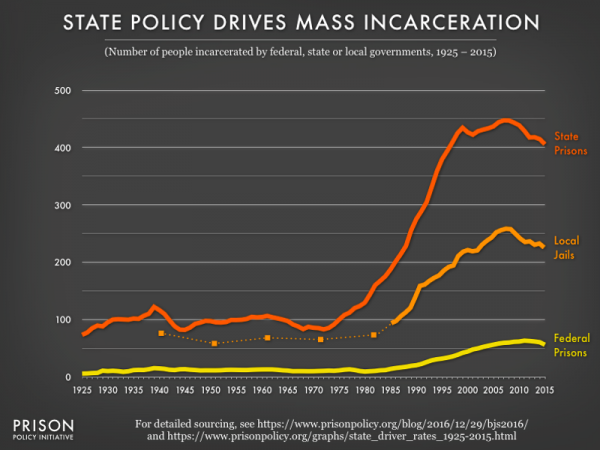

Consider the statistics: In the US, federal prisons house about 12 percent of the overall prison population. That is, to be sure, a significant number in such a big system. But it’s relatively small in the grand scheme of things, as this chart from the Prison Policy Initiative shows:

One way to think about this is what would happen if President Biden used his pardon powers to their maximum potential — meaning he pardoned every single person in federal prison right now. That would push down America’s overall incarcerated population from about 2.1 million to about 1.9 million.

That would be a hefty reduction. But it also wouldn’t undo mass incarceration, as the US would still lead all but one country in incarceration: With an incarceration rate of around 600 per 100,000 people, only the small country of El Salvador would come ahead.

Similarly, almost all police work is done at the local and state level. There are about 18,000 law enforcement agencies in America — only a dozen or so of which are federal agencies.

Biden’s plan acknowledges this by including provisions that ask the states to reform their criminal justice systems and reduce incarceration. At the same time, studies show that previous efforts to encourage states to adopt criminal justice policies with federal funding incentives, including the 1994 crime law, had little impact; by and large, cities and states embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues only if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall almost wholly to cities, counties, and states.

Notably, too, those local and state reforms will require at least some focus on reducing punishments for violent crimes, because the majority of people in state prisons are violent offenders. But Biden’s plan, like most criminal justice reform proposals, focuses largely on nonviolent and drug offenses.

All of that raises questions about how effective Biden’s plan would be for truly reversing incarceration.

At the very least, though, the plan would begin to rework the federal system — which is still the largest in the country. And it tries to signal to criminal justice reformers that, after years to the contrary, Biden is now on their side.

Sourse: vox.com