On Sunday, President Donald Trump said that many women were “extremely happy” with the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, despite the sexual assault allegations against him.

“They’re thinking of their sons, they’re thinking of their husbands, their brothers, their uncles, and others,” Trump said.

It’s become a common refrain — the #MeToo movement, critics claim, is leading to an epidemic of false accusations against men. And over the course of the last few months, that refrain acquired a hashtag: #HimToo.

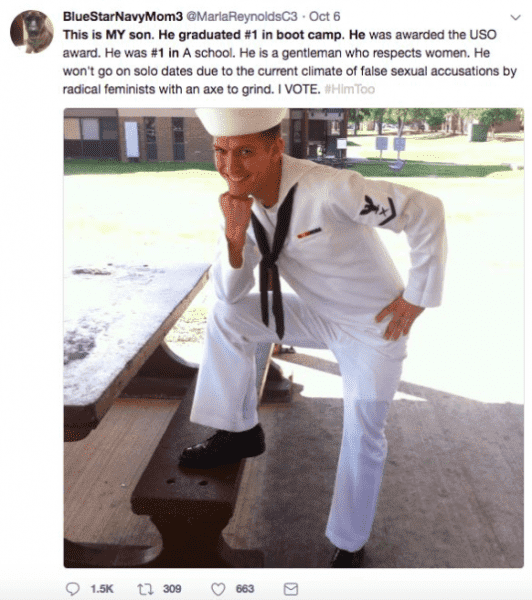

As Vox’s Aja Romano notes, the hashtag gained new attention earlier this week when Twitter user BlueStarNavyMom3 used it to claim that the #MeToo movement had made her son unwilling to go on “solo dates” with women — and her son, Pieter Hanson, joined Twitter to politely correct her.

BlueStarNavyMom3’s initial tweet inspired a lot of funny memes, but the exchange also prompted a serious discussion about the role of men in the #MeToo era. Trump and others appear eager to pit men against women, implying that taking claims of sexual misconduct seriously means unjustly ruining men’s lives.

But men aren’t just the subject of misconduct allegations — they also experience sexual assault and harassment at significant rates. One in six men has experienced sexual violence involving physical contact in his lifetime, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control. As Amanda Wallwin, chief of staff for New York State Assembly Member Dan Quart, tweeted, men are probably more likely to be assaulted than falsely accused.

Our cultural expectations around sex and masculinity, however, lead to a lack of awareness of sexual violence against men. “A lot of people colloquially just see this sort of thing as something that happens to women,” Seth Stewart, director of development and communications at 1in6, a group that offers resources for male-identified survivors of unwanted sexual experiences, told Vox.

#HimToo could make matters worse. The hashtag is a symptom of a misconception that’s spread as part of the backlash to the #MeToo movement: the idea that false accusations are just as serious a problem as actual sexual misconduct. This false equivalency not only misrepresents the prevalence of false accusations — by presenting sexual assault as something women report and men are accused of, it could perpetuate myths that hurt male survivors.

It’s not just Harvey Weinstein: More than 250 powerful people have been accused of sexual misconduct. Here’s the list.

#HimToo is part of a bigger pattern

The hashtag #HimToo has been around since at least 2015, Emma Grey Ellis reports at Wired, and it wasn’t always political — initially, it “referred to any male who was also doing something” — “if you went to go get froyo with your boyfriend, you might tweet ‘I love Pinkberry. #HimToo.’” After the #MeToo movement gained steam in October 2017, some began using #HimToo to call out men for sexual misconduct — and, occasionally, to draw attention to issues facing male survivors. But by sometime earlier this year, it was used to refer to false accusations.

Members of the anti-feminist subreddit Men Going Their Own Way started using the hashtag this summer, Ellis notes — it cropped up in posts like this one, referencing an Associated Press story about a former police officer freed from prison after the woman who accused him of rape admitted she lied in her testimony. (Incidentally, the woman maintains that the officer really did rape her when she was 13 years old; her “lie,” she says, was telling the court she had never been sexually active before, when in fact her stepfather had sexually assaulted her.) In early October, it began to appear on Twitter in reference to the allegations against Kavanaugh.

The real breakout moment for #HimToo, though, was BlueStarNavyMom3’s tweet (her account has since been deleted) on October 6:

The tweet tapped into a larger narrative emerging alongside #MeToo: the notion that false allegations are rampant. Trump has fed this narrative for months, tweeting in February, “Peoples lives are being shattered and destroyed by a mere allegation. Some are true and some are false. Some are old and some are new. There is no recovery for someone falsely accused — life and career are gone. Is there no such thing any longer as Due Process?”

But his rhetoric kicked into high gear after allegations against Kavanaugh by Christine Blasey Ford and others became public. “It’s a very scary time for young men in America when you can be guilty of something you may not be guilty of,” he said on October 2. “This is a very difficult time.”

Asked if had a message for young women as well, he said, “Women are doing great.”

He wasn’t the only one. Presidential counselor Kellyanne Conway said on Sunday that during the Kavanaugh confirmation fight, women in America saw a man suffering from “political character assassination, and also we looked up at him and saw possibly our husbands, our sons, our cousins, our coworkers, our brothers.”

On the day Ford and Kavanaugh testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee, right-wing activist Laura Loomer tweeted that “men aren’t safe in America anymore.”

To hear Loomer and others tell it, American men are suffering from an onslaught of false accusations. And Trump’s comments implied that such accusations were an even bigger problem than sexual assault itself. This is the larger picture of which #HimToo forms a particularly visible part.

Focusing on false allegations ignores the reality of male survivors

Despite Trump’s remarks, false allegations of sexual assault are rare: Experts estimate that between 2 and 8 percent of sexual assault reports are false. As Salon’s Amanda Marcotte points out, not everyone who makes a false report accuses a real person — some “blame a made-up stranger.” That means the percentage of sexual assault reports that turn out to be false allegations against innocent people is even smaller than the rate of false reports more generally.

It’s difficult to determine exactly how many men have been falsely accused, but extrapolating from the number of men in America and the percentage of false reports (even using the highest estimates), it’s likely that fewer than 0.005 percent of American men are falsely accused each year.

Being falsely accused of a crime is, of course, very serious. But far from being some sort of epidemic requiring a campaign of self-protection, being falsely accused of sexual assault is very, very uncommon for American men. It’s far more common for men to be sexually assaulted.

According to CDC data gathered between 2010 and 2012, one in three women and one in six men have experienced some form of sexual violence involving physical contact. And a survey conducted earlier this year by the group Stop Street Harassment found that 81 percent of women and 43 percent of men had been harassed or assaulted at some point in their lives.

Sexual misconduct against men is probably underreported, Stewart told Vox. Male survivors of what others might see as sexual assault might describe the experience as hazing, physical abuse, or humiliation, Stewart said, and “if they talk to someone who says ‘it was abuse, it was rape,’ many men will psychologically go into hiding.”

American conceptions of sex, assault, and masculinity can make it harder for male survivors to come forward or even acknowledge their experiences to themselves, Stewart said. While women are often blamed for being sexually assaulted, they said, “for men, as opposed to saying, ‘it was your fault,’ the saying is, ‘it didn’t happen.’”

Men are assumed to always want sex: “if a boy has sex with a much older woman he’s somehow gotten lucky or scored,” Stewart said. This leaves men with unwanted sexual experiences feeling ignored or disbelieved. Men are also expected to be independent, in control, and powerful, which can make it hard for them to admit to an experience they didn’t want. And there’s a lack of public understanding that men’s bodies can respond to sexual contact even if that contact is unwelcome, Stewart said.

The #MeToo movement has actually inspired many male survivors to seek help. Traffic to the 1in6 website skyrocketed in 2017 as the movement grew, Stewart said. The group also saw an uptick in requests for services in the wake of Ford’s testimony.

“This is why we are so thankful, and I think many male survivors are so thankful, for things like #MeToo, for the courage of someone like Dr. Ford,” Stewart said. “It inspires survivors across all groups.”

Using #HimToo to focus on false allegations against men, meanwhile, can discourage all survivors from coming forward, they explained: “Seeing #HimToo used to support a man who has been accused of sexual abuse or assault explicitly casts doubt on a survivor’s story, thus enforcing secrecy over

To hear Trump, Conway, and others tell it, sexual assault breaks down neatly along gender lines: women make accusations, men are accused. (It’s not clear what percentage of these accusations #HimToo advocates believe are actually true.) But in fact, people of all genders can be sexually assaulted. And by telling one false story about assault — women are lying to try to destroy men — #HimToo advocates are keeping the real stories from being told.

Sourse: vox.com