enemy: private equity” alt=”Elizabeth Warren’s latest Wall Street enemy: private equity” />

enemy: private equity” alt=”Elizabeth Warren’s latest Wall Street enemy: private equity” />

Elizabeth Warren has a plan for the private equity industry — and they’re probably not going to like it. For workers at the now-defunct Toys R Us, Payless, and Shopko, had her plan already been enacted, it could have made a difference.

This week, the Massachusetts Democrat unveiled the latest plank of her “economic patriotism” proposal to push American companies to operate in a fairer way and focus more on the interests of workers and consumers, this time with a focus on Wall Street. In a Medium post, she laid out various ideas for ways to end Wall Street’s “stranglehold” on the economy. “To raise wages, help small businesses, and spur economic growth, we need to shut down the Wall Street giveaways and rein in the financial industry so it stops sucking money out of the rest of the economy,” she wrote.

Warren also unveiled new legislation — the Stop Wall Street Looting Act of 2019 — which takes aim at a very specific corner of the financial industry: private equity, firms and investment funds that make money by buying and selling companies. The bill would overhaul the way private equity is governed and require the industry to change some of its most lucrative business practices. It would also offer more protections for workers when their private equity-owned employers go south.

Would it kill the private equity industry entirely? Probably not. But it would change a lot of the incentives around the way firms do business, require them to have more skin in the game, and make it a lot harder for them to make money if the businesses they buy fail. It would mean that to make a lot of money, they’d have to make really good bets.

The proposal is also another way to shine a spotlight on economic inequality and the ways workers often lose out to moneyed interests on Wall Street.

“She’s pretty much proposing a total revamping of the way private equity firms do business,” said Robert Willens, a New York-based tax analyst and former managing director at Lehman Brothers. “She didn’t miss anything, that’s for sure.”

The private equity industry, predictably, isn’t happy about it.

What private equity does, briefly explained

Private equity firms are private, as the name suggests, as opposed to publicly traded companies such as Apple and Walmart. Their investors are generally institutional investors, such as pension funds, or accredited investors — investors who meet a certain set of criteria that allow them to make riskier bets. Some big-name examples are the Blackstone Group, the Carlyle Group, and Bain Capital, where Mitt Romney spent part of his private sector career.

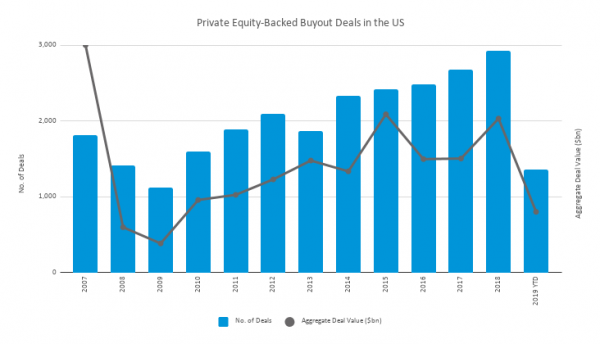

The general idea behind private equity firms is that they buy companies that are struggling or that they believe have a high potential for growth, repackage them or speed up their growth, and then sell them to another firm, take them public, or find some other sort of exit for them. According to the alternative assets tracking firm Preqin, US private equity deals have increased steadily in the US since 2013 after declining following the financial crisis.

Sometimes the outcome is positive, and sometimes it’s not. The companies they buy can also fail or go bankrupt — including, Warren and many others allege, because of private equity practices that strip the companies of their value.

The retail graveyard is filled with private equity buys, including Toys R Us, Sears, KB Toys, and Payless Shoes. Private equity firms have enacted mass layoffs at local newspapers and shuttered some altogether. Casinos, grocery stores, and many other businesses have failed in the hands of private equity firms.

To a certain extent, that makes sense: Private equity firms, by definition, often target companies that are underperforming, so of course sometimes a turnaround won’t work out. The issue Warren identifies is that funds can go in without a sound turnaround plan in the first place, and they can still make a ton of money off the deals even when they fail. And they sometimes take out loans through the companies they acquire and use the funds to line their pockets and pay dividends no matter how the company performs. Those are the issues Warren wants to address.

Warren doesn’t want to kill private equity entirely — but she would make some big changes

Warren’s Medium post and legislation call for putting a stop to whats she calls “legalized looting” — overhauling the rules and regulations surrounding the private equity industry. She notes that since 2009, investors have put $5.8 trillion into private equity globally, and today, 35,000 private equity-owned companies employ 5.8 million workers. And in her view, there’s a lot of bad behavior going on:

Warren’s plan, outlined in full in her proposed legislation, would make a number of changes to how private equity firms are governed. Here are some examples:

- Private equity firms extract monitoring and transaction fees from the target companies they buy and take dividends from those firms for themselves and investors. Warren’s bill would put a 100 percent tax on those fees and ban dividends for two years after a transaction.

- The bill requires funds to share responsibilities and liability for the target company’s debt, including for legal judgments, violations of the WARN Act (a law that requires companies to give 60-day notification to employees about plant closings and mass layoffs), and pension-related violations. So if a company takes on a bunch of debt in its turnaround effort and fails, the private equity fund is on the hook to deal with the fallout, which isn’t the case now.

- The bill closes the carried interest loophole.

- It moves certain parties — namely, workers and consumers — up the totem pole in bankruptcy proceedings. It prioritizes worker pay in bankruptcy proceedings and clarifies that gift cards count as consumer deposits, moving them up in line for payouts as well.

- The bill increases transparency to investors, including requiring the Securities and Exchange Commission to issue rules that require annual

Essentially, Warren’s proposal sets out to accomplish a lot of things — she wants to require private equity firms to be more on the hook for the risks they take than they are now, stop them from making money off bad bets, and make sure workers, consumers, and investors don’t get shortchanged.

“The [firms] that face a problem are the ones that really bought the companies not to run them as a going concern so much as to make sure they got their money out and made lots of money for themselves and for their investors,” Appelbaum said.

Also this week, Warren and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez sent a letter to Sun Capital, the private equity firm that owned the now-liquidated Shopko, asking the firm what it plans to do about severance pay for former employees. “While you will walk away with a healthy return, the workers who kept the stores running despite every obstacle you threw in their path will come away with nothing,” they wrote.

The private equity industry is, unsurprisingly, not happy about this

The private industry trade group the American Investment Council was, predictably, not thrilled with Warren’s proposal. The group’s president and CEO, Drew Maloney, argued in a statement that private equity is an “engine for American growth and innovation” and specifically laid out private equity investments in Massachusetts. The council also hit back at Warren on Twitter and pointed out the jobs it oversees and the investors it tries to make money for, including public pension funds.

In other corners, Warren’s proposal got a lot of praise. In the Senate, the bill is being co-sponsored by Sens. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH), and Reps. Mark Pocan (D-WI) and Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) introduced the legislation in the House. It has also earned the backing of high-profile Democrats, including fellow 2020 contenders Sens. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and “Squad” members Reps. Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) and Rashida Tlaib (D-MI).

Other backers include the AFL-CIO, Communications Workers for America, Public Citizen, the American Federation of Teachers, and the Working Families Party. “Private equity and hedge funds now wield enormous influence over the American economy, often with terrible consequences for workers and communities,” said Lisa Donner, executive director of Americans for Financial Reform, one of the groups backing the bill, in a statement. “We need effective rules of the road to stop predatory practices by these Wall Street giants.”

On Thursday, Warren and other Democratic lawmakers hosted workers who have been harmed by private equity firms for an event on Capitol Hill, where those workers were invited to share their stories.

This gives Warren a new way to talk about economic inequality

In her Medium post, beyond private equity reforms, Warren also lays out a number of other proposals, including enacting a modern-day Glass-Steagall (which puts a wall between commercial and investment banking), bringing about postal banking, and reversing the weakening of certain rules surrounding big banks under President Donald Trump.

While the affected financial actors probably wouldn’t like the changes — though plenty of workers and consumers would — they probably wouldn’t have a significant macroeconomic impact on the United States, said Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, in an email. “They will not materially change the flow of credit to the economy,” he said. “The impact of the reforms on the safety and soundness of the financial system will also be on the margin.”

And, of course, it’s not clear how much of a chance this private equity legislation has of becoming law, at least not until 2021.

But this proposal, and specifically the private equity plank, gives Warren a new way to hammer home her message on economic inequality and creating a system that is fairer for everyone. She has already laid out multiple proposals along those lines, including the Accountable Capitalism Act, a plan for economic patriotism, and a proposal to jail CEOs if their companies behave badly. This is another step.

“The senator’s bank proposals don’t break new ground as she has been whistling that tune since before entering politics,” Isaac Boltansky, the director of policy research at Compass Point Research & Trading, said in an email. “The private equity proposals, on the other hand, represent a fresh front in her economic platform that provides a means of focusing the conversation directly on economic inequality.”

Warren has also been able to capitalize on some high-profile examples of private equity deals gone wrong. One example: Toys R Us, an iconic brand that went bankrupt in 2017, after which workers spent months protesting for severance.

This is another way for Warren to hammer home her message of unfairness in the US economic system and the ways corporate executives, managers, and the wealthy get ahead while most others are left behind. And it doesn’t hurt to remind people she’s a bankruptcy expert.

Sourse: vox.com