An unexpected Saturday morning presidential tweet briefly — and without further explanation or elaboration — raised the prospect of a perhaps-imminent pardon of former boxing champion Jack Johnson, the victim of a century-old act of racial injustice.

Johnson has been dead for more than 70 years, so the practical stakes, in this case, are low. But a pardon would be a symbolically potent recognition of the kinds of racial disadvantage even relatively privileged African Americans have experienced in American history — a theme whose relevance endures today.

Of course, a symbolic act of solidarity with people of color mistreated by the criminal justice system seems a little off brand for Trump. But Johnson’s case is far enough back in time — and has enough support from old, white, male, conservative boxing fans — that moving forward would be unlikely to trouble anyone in Trump’s base. Meanwhile, at least one aspect of a Johnson pardon would be extremely on brand: Pulling the trigger would be a rebuke to former President Barack Obama, who considered a pardon but didn’t go through with it.

Even better, it would be an example of the very disregard for the norms and procedures of office for which Trump is so frequently criticized paying off and serving the public interest. Plus, it would make Sly Stallone happy, and he played Rocky.

Who was Jack Johnson?

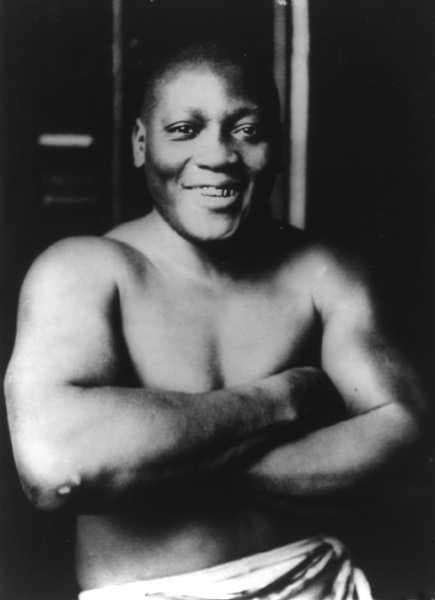

Born in a poor (though, according to Johnson’s recollections, racially integrated) section of Galveston, Texas, to former slaves in 1878, Johnson attended school for five years before quitting in favor of work on the docks. He boxed as an amateur during his teen years and made his professional debut in Galveston in 1898.

Boxing was, at the time, a semi-segregated endeavor with a separate World Colored Heavyweight Champion title available to black boxers who were unable to compete with whites for the title of World Heavyweight Champion. At the same time, professional boxing has always been a decentralized affair, and black and white fighters were able to meet outside the context of championship bouts.

And, indeed, as early as 1901, Johnson fought the Jewish boxer Joe Choynski in a match that landed both contestants in jail (prizefighting was illegal in Texas at the time) after one of the very few defeats in Johnson’s career.

In 1902, Johnson defeated Frank Childs, a two-time former Colored Heavyweight Champion, and in 1903 he beat Denver Ed Martin on points to become World Colored Champion himself.

Johnson, however, set his sights higher and was determined to challenge James Jeffries for the title of World Heavyweight Champion. Jeffries, however, refused and eventually retired undefeated in 1905.

In 1907, Johnson fought — and beat — Jeffries’s predecessor, Bob Fitzsimmons, as part of an ongoing campaign waged in the press to taunt (white, Canadian) Heavyweight Champion Tommy Burns into fighting him in December 1908.

Johnson, defying the expectations of the white press, beat him in a well-publicized match in Australia and touched off what can only be termed an outbreak of mass racial hysteria, in which a succession of “Great White Hope” figures were sought to dethrone Johnson, all of whom fell short. White racists’ hopes then alighted on the still-undefeated Jeffries, hoping that he could beat Johnson and reclaim the title for the white race.

When, instead, Johnson won their July 4, 1910, bout — dubbed the Fight of the Century — the reaction was an immediate outbreak of white supremacist violence in multiple American cities. As a contemporaneous United Press International story recounts, “riots between whites and blacks followed in a dozen cities of the country, and reports this morning increase the number and add to the list of injured.”

Three African Americans were killed in Uvalda, Georgia; in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district, one was “seized by angry whites and strung up to a lamppost,” though police cut him down before he died, and “another mob attempted to lynch a negro buying a paper.”

Jeffries, however, came away humbled by the experience, explaining: “I could never have whipped Johnson at my best. I couldn’t have hit him. No, I couldn’t have reached him in 1,000 years.”

Unbeatable in the ring, Johnson was instead taken down by the law.

Why does Jack Johnson need a pardon?

Johnson scandalized the conventional opinion of his time by not only out-boxing white fighters but also openly carrying on relationships with a series of white women, three of whom he married.

The prime of Johnson’s career roughly corresponded with what was probably the nadir of civil rights in America in the post-Civil War years. In the 1870s, 1880s, and even to an extent the 1890s, African Americans served in Congress and the national Republican Party saw attempting to uphold black voting rights as a political imperative.

By the early 20th century, however, GOP commitment to President Abraham Lincoln’s legacy had largely evaporated, while the Long Civil Rights Movement had yet to begin making an impact on Northern Democrats. When President Theodore Roosevelt had a 1901 dinner meeting with Booker T. Washington at the White House, it produced a massive racial backlash. Woodrow Wilson’s election in 1912 would bring formal segregation to federal offices and the District of Columbia.

In this difficult political context, Johnson was viewed as a menace by white supremacists but also as a problematic figure by black political leaders who were invested in a form of respectability politics that he flagrantly violated.

In his 2006 book, Unforgivable Blackness, Geoffrey C. Ward quotes Washington’s anti-Johnson remarks to an audience at the Detroit YMCA:

In the summer of 1912, Johnson met Lucille Cameron, and they were frequently seen in public together shortly thereafter.

Cameron’s mother went to the press and argued, “Jack Johnson has hypnotic powers, and he has exercised them on my little girl. I would rather see my daughter spend the rest of her life in an insane asylum,” she further argued, “than see her the play thing of a ni**er.”

On October 18, 1912, Johnson was arrested for violating the Mann Act — a 1910 law making it a federal crime to transport across state lines “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” This vaguely worded statute was in theory designed to combat prostitution or human trafficking, but in practice could be applied much more broadly.

The October case fell apart, but Johnson was rearrested in November, married Cameron in December, and was convicted in June 1913, after which time he skipped bail, resurfaced publicly in Montreal, and then lived in exile abroad with Cameron for seven years before surrendering to authorities in 1920.

During Johnson’s exile years, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote of Johnson’s critics, “Of course some pretend to object to Johnson’s character. But we have yet to hear, in the case of White America, that marital troubles have disqualified prize fighters or ball players or even statesmen. It comes down, then, after all to this unforgivable blackness.”

Several members of Congress have been seeking a Johnson pardon

In the wake of the civil rights movement, Du Bois’s view that Johnson was the victim of unjust racial persecution has become conventional wisdom. The January 2005 Ken Burns documentary that borrowed Du Bois’s memorable phrase — Unforgivable Blackness — for its title further pushed Johnson’s case into the public eye.

The year before Burns’s documentary came out, Sen. John McCain (R-AZ) and Rep. Peter King (R-NY), both boxing fans, first introduced legislation calling for an official pardon of Johnson. McCain and King succeeded in getting a “sense of Congress” resolution expressing the idea that Johnson deserves a pardon included in the bipartisan 2015 No Child Left Behind rewrite. In June 2016, they were joined by Sen. Harry Reid (D-NV) and Rep. Gregory Meeks (D-NY) in writing a letter to President Obama on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of Johnson’s death to urge a pardon.

With Reid retired, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ) has taken his place as the go-to Senate Democrat on this issue, joining with McCain, King, and Meeks to write a 2017 resolution once again seeking a pardon for Johnson.

Stallone, a Republican boxing fan like McCain and King, is apparently also on the “pardon Johnson” bandwagon. Since Trump is apparently more interested in the views of famous movie stars than of US senators, Stallone seems to have persuaded Trump to consider the matter seriously.

A Johnson pardon would be a rebuke to Obama

The momentum for a Johnson pardon gathered several times during President Obama’s two terms in office, but it was always rebuffed by the administration. This despite the fact that, in some ways, it would seem like a natural symbolic cause for the country’s first black president to embrace.

But he never did, perhaps in part because black America has traditionally had somewhat mixed feelings about Johnson as a civil rights icon, but more fundamentally because Obama was a stickler for rules. Presidential pardon claims are normally processed by the Department of Justice’s Office of the Pardon Attorney, which does fairly extensive research and investigations on claims for presidential clemency.

The OPA’s standard operating procedure is to not bother wasting resources on people who are dead, and the Obama administration neither wanted to go outside the OPA process nor get them to change their policy.

Trump, by contrast, has already bypassed the OPA to pardon Joe Arpaio and Scooter Libby in moves that have been mostly denounced by progressives as examples of Trump’s dangerous disregard of constitutional norms. There’s considerable concern on the left that Trump will attempt to pardon his way out of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation and undermine the rule of law.

The fact that the presidential pardon power is so unconstrained by the text of the Constitution — allowing the president to pardon essentially anyone of any federal crime for any reason (or no reason at all) — is a somewhat embarrassing and potentially alarming fact. A president’s political allies could, in theory, murder opposition members of Congress on the streets of Washington (where, not being a state, murder is a federal crime) and then get pardoned for their trouble. So the OPA process has been created over the years to “tame” and bureaucratize the process.

Pardoning Johnson would be a way of delivering something Obama couldn’t — or wouldn’t — and of specifically highlighting that Trump’s oft-criticized way of doing business has some real upsides. Trump has faced relentless criticism for his norm violations and rule-breaking, but it’s unquestionably the case that at least some of his appeal was precisely the sense that a sclerotic American political system has become excessively unresponsive to the public’s needs and desires.

If Johnson can’t get a posthumous pardon even when more or less everyone agrees he deserves one out of sheer bureaucratic inertia, what hope is there for causes that face actual opposition from organized interest groups?

For Trump to simply do the thing would both redress a historical injustice and serve as an object lesson in the real upside implicit in his freewheeling approach to the presidency.

Sourse: vox.com