In January 1996, the centerpiece of President Bill Clinton’s State of the Union address was a declaration that “the era of big government is over.” 23 years later, the brightest young star in the Democratic Party is Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, who wants to nationalize the health insurance industry and pass a Green New Deal that would zero-out US carbon emissions in the next 12 years.

When Anderson Cooper labeled this a “radical” agenda in a Sunday night interview with the Congress member, she proudly embraced the label.

“I think that it only has ever been radicals that have changed this country. Abraham Lincoln made the radical decision to sign the Emancipation Proclamation. Franklin Delano Roosevelt made the radical decision to embark on establishing programs like Social Security,” she said. “If that’s what radical means, call me a radical.”

Much of the interview is a tap-dance on the grave of Clinton-era liberalism. The Clinton administration was deeply concerned with budget deficits; Ocasio-Cortez told Cooper she didn’t need a plan to pay for her proposals. Clinton passed welfare reform to end black Americans’ alleged “dependence” on the welfare state; Ocasio-Cortez called President Donald Trump a racist, condemning deployment of the “historic dog whistles of white supremacy.”

Ocasio-Cortez is, of course, not the president, or even the Democratic Party’s leader. If anything, though, that makes the contrast more striking: Here is a first-term member of Congress who doesn’t yet have the power to set her party’s agenda, and yet has captured the imagination of the party rank-and-file and the national media.

The contrast between Ocasio-Cortez and Bill Clinton points to a very interesting, and largely misunderstood, division in the Democratic Party. For some time now, the Democratic voting base has been much more aligned with the Congress member than the former president, embracing more progressive positions on everything from taxes to immigration to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. But the party’s elected ranks, and especially its leadership, hasn’t moved nearly as much.

This gap, between a more progressive party base and the more cautious establishment, is part of what makes candidates like Ocasio-Cortez so popular. They are giving Democratic voters what they want, which is an unapologetic and aggressively progressive party.

It’s not always clear what being “more progressive” actually means. Many of the plausible Democratic 2020 presidential candidates, ranging from Sens. Cory Booker to Elizabeth Warren to Bernie Sanders, have different visions for the party’s future. The fight between so-called “liberals” and “leftists,” which rages on my Twitter feed daily, is a fight to define just exactly what it means to be “progressive” in a post-Clinton era.

But regardless of which factions win this fight, it’s clear that Clinton-style centrism is dead in the water. Its advocates in the party are older and out of step with the party’s base. Elected Democrats may not fully realize it yet, but the era of small-government liberalism is over.

The voters have shifted, the elected officials haven’t (as much)

The progressive shift in the Democratic voting base in the past 20 years is clear and profound. The Atlantic’s David Graham laid out some of the most striking data in a November summary:

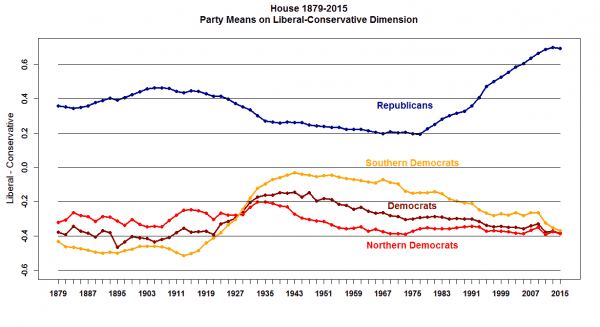

The party’s elected officials, though, don’t wholly reflect that shift. The following chart, from VoteView, charts the two parties’ DW-NOMINATE scores (a political science metric of officials’ ideology based on voting record) from the 19th century to 2015. The Democratic Party’s average, in dark red, shows relatively limited movement between the mid-’90s and mid-2010s:

The contrast with the Republican line in the chart couldn’t be clearer. Both Republican voters and elected officials have become increasingly conservative, even reactionary and nativist, in the past several decades. The Democratic base is not a mirror image of the Republican base — it’s not nearly so radical — but it has clearly tilted to the left over the same time. The difference is that the party’s elected officials haven’t really followed suit.

When I chat with rank-and-file Democrats, the kind of people who tend to reliably turn out in party primaries, they seem quite aware of this discrepancy. You frequently hear a hunger for politicians who are unapologetically progressive, who counter Republican radicalism with boldness, rather than the more cautious approach you get from a lot of elected Democrats.

This effect appears to have opened up space for more forthrightly progressive candidates to win primaries. In July 2018, YouGov asked self-identified Democrats whether they wanted candidates for the midterm elections to be “more or less like Bernie Sanders.” Fifty-seven percent said they wanted more Sanders-esque candidates; a scant 16 percent said less.

The actual makeup of party primaries is starting to reflect the base’s interest in more aggressive candidates. An October Brookings report sorted the Democratic primary field into three categories: Moderate, Establishment, and Progressive. It found that the percentage of “Moderate” candidates fell in half between 2014 and 2018, while the percentage of “Progressives” went up by around 60 percent.

This doesn’t mean a Sanders/socialist takeover of the party is imminent. It is very far from clear that Democratic voters are more interested in Ocasio-Cortez’s democratic socialism then, say, Elizabeth Warren’s welfare-state capitalism. The fight to define “progressivism” is still ongoing.

But the reason this battle between progressive factions is happening in the first place is because there’s been a rupture with the past. The official party is somewhat out of step with its voters, still more Clintonite than many voters would like. This has opened up space for a shift in a progressive direction, making some kind of change inevitable. The only question is where the party ends up.

Sourse: vox.com