In 2016, Brock Turner was sentenced to six months in jail for sexually assaulting a woman who was drunk and unconscious — a sentence widely considered so outrageous that it led to weeks of national furor. And Turner ended up serving just three months, setting off yet another firestorm.

Now the man who handed down that sentence, Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Aaron Persky, is facing a recall campaign. On June 5, local voters will get a chance to kick Persky off the bench. If the effort is successful, Persky would be the first judge successfully recalled in California since 1932, and the first in the US since 1977.

The Turner case, in the context of the wider #MeToo movement, is at the center of the recall campaign. At the time the sentence was handed down, it drew particular criticism because of Turner’s race and socioeconomic background — he was a white Stanford student and a member of the school swim team. The sentence was widely viewed as grossly inadequate and the result of privilege. As CNN host Jake Tapper noted at the time, “What if it had been a black or Latino man at a less prominent college?”

The case inspired the recall campaign, led by Stanford Law School professor Michele Dauber. But the campaign has argued that the problems with Persky run deeper — citing several other cases in which Persky went easy, in the campaign’s view, on people who committed sexual or domestic violence.

“Judge Persky has a history of what we regard as bias in cases of sexual assault, sexual violence, violence against women,” Dauber told me, “particularly where the perpetrator is an athlete or otherwise privileged in some way.”

Some criminal justice experts and advocates, however, have stood by Persky. For some of them, the issue is not whether Turner’s sentence was appropriate — many of them say that it wasn’t. The broader concern is the message that a successful recall campaign could have on the criminal justice system as a whole: If judges suddenly have to worry that lenient sentences could lead to public outrage and even a recall campaign, then maybe they will err toward harsher sentences — and that could perpetuate mass incarceration.

“The simple story is it’s going to make judges more punitive,” John Pfaff, the author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, told me. “Why take that risk?”

Persky, for his part, hasn’t done much to help his cause. He’s rarely spoken to media about the recall campaign or the Turner ruling. One of the few times he did, he compared the recall effort to the backlash against the justices who handed down the Brown v. Board of Education ruling — a landmark civil rights decision against segregation in public schools, which drew ire from Southern states in particular. “Imagine for a moment if those federal judges had been subject to judicial recall in the face of that unpopularity,” he said.

To understand all of this, though, let’s start with the Turner trial — and the ruling that sparked the recall effort.

Supporters of the recall say Persky has a bad history with sexual assault cases

Brock Turner was accused of sexually assaulting a 22-year-old woman, whose identity has remained anonymous, in 2015. Turner, who was 19 at the time, and the victim were drunk following a fraternity party. But it was Turner who, behind a dumpster as the victim lay on the ground, unresponsive, allegedly took off her underwear and penetrated her vagina with his fingers.

According to court records, two Stanford students caught Turner in the act, Turner then attempted to flee, and the students tackled him and held him down until the police arrived.

The victim said she found out the details of the assault on the news, because she had been too intoxicated to remember the specifics. According to police reports, the victim remained unconscious for three hours after paramedics arrived, even as they administered treatment.

“This was a violent assault,” Dauber said. “This was not two kids having drunk sex semi-consensually. This was a completely unconscious person being violently violated in a public space.”

Turner was sentenced to six months in jail and three years of probation after he was convicted of three sexual assault felonies in 2016, although he ultimately served only three months in jail. Prosecutors had asked for six years in prison, and the maximum possible sentence was 14 years.

“In order to not give Mr. Turner prison,” Dauber argued, “Judge Persky had to take an additional extraordinary step and he had to make a finding on the record that this was an ‘unusual case’ and that the interest of justice required probation. And that is the heart of our argument that he abused his discretion.”

Meaghan Ybos, as an advocate for sexual assault victims and co-founder of People for the Enforcement of Rape Laws, has a very different view of the Turner case. She argued that the punishment Turner received was appropriate because it considered his young age, lack of criminal history, and the local probation office’s recommendation that he shouldn’t get a state prison sentence. And, she said, at least the case was prosecuted — which isn’t true for the great majority of sexual assault allegations.

“The Brock Turner case was investigated by the police. It was prosecuted. And the prosecutors did get a conviction,” Ybos told me. “Compare that to the vast majority of sexual assault cases — [they] never reach a courtroom. That in itself makes the [Turner] case a success in a sense.”

She added, “Now, it’s not going to be a success in that a criminal justice outcome makes it good. But that’s never been the function of the criminal justice system.” Ybos argued that the criminal justice system can never make anyone whole after an awful crime, and is instead focused on ensuring people’s constitutional rights when they’re accused of, not victimized by, a crime.

Dauber countered that the probation office’s report was not a good standard because it was based, at least in part, on the victim reportedly telling the probation office that she did not want a prison sentence for Turner. But the victim told the court — in a statement that went viral — that “I told the probation officer I do not want Brock to rot away in prison. I did not say he does not deserve to be behind bars. The probation officer’s recommendation of a year or less in county jail is a soft timeout, a mockery of the seriousness of his assaults, an insult to me and all women.”

Persky’s defenders also argue that Turner’s punishment extends beyond jail time: He has to complete three years of probation, was forced to withdraw from Stanford, was banned for life from swimming competitively in the US, and had to register as a sex offender.

For the campaign, though, it goes beyond Turner. On its website, it lists several other cases in which, according to the campaign, Persky “appeared to favor athletes and other relatively privileged individuals accused of sex crimes or violence against women.”

One of those other cases, reported by Katie Baker at BuzzFeed, has drawn criticism even from some of Persky’s biggest supporters.

In 2015, Ikaika Gunderson, 21, beat and choked his ex-girlfriend, confessed to police, and “three months later pleaded no contest to a felony count of domestic violence,” according to Baker.

Instead of giving Gunderson prison time — potentially up to four years — Persky cut him a break. He delayed sentencing for more than a year to give Gunderson a chance to attend the University of Hawaii and play football, as he’d always dreamed of. At the end of the year, Persky said he’d reevaluate the charges against Gunderson if he completed, among other requirements, a domestic violence program. This was very unusual and may have violated federal law that puts restrictions on where offenders can move out of state, Baker noted.

Persky, however, didn’t have Gunderson monitored. Within a year, Gunderson failed to meet requirements in the agreement (including part of the domestic violence program), dropped out of the University of Hawaii, and was arrested for another domestic violence charge in Washington state.

Retired Judge LaDoris Cordell, who’s appeared on national news outlets typically defending Persky, said that “[t]here are so many problems with how this case was handled that I’m not even sure where to start.”

There are other cases with questionable sentences and outcomes, including one regarding child pornography and another involving a football player and domestic violence.

“This is a judge who has poor judgment in the area of sexual assault and violence against women,” Dauber said. “He does not understand it. He does not properly weigh the harm of sexual violence and does not properly assess the blame for these crimes to the perpetrator and the perpetrator alone.”

Persky’s supporters argue that these are a handful of cases out of the thousands that Persky oversaw. Both public defenders and prosecutors who’ve argued in the judge’s courtroom have come out on his side, arguing that he’s generally reasonable and fair. Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen told me that although he disagreed with the sentence Turner got, “other judges in our county and other judges in our state would have made the same decision.”

Pfaff pointed out that the recall campaign hasn’t systematically proven that other judges in the state are necessarily better than Persky. “They haven’t demonstrated that Persky is the worst judge,” Pfaff said.

For supporters of the recall campaign, the cases are still alarming examples of what Persky often, in their view, gets wrong. “How many cases are women allowed to give him before we can call him out?” Dauber asked.

Opponents worry the recall could send a dangerous message

So why has a story about a local judge become a national issue? Part of it is that sexual and domestic violence is getting a lot more attention because of the #MeToo movement. But in addition to that, some criminal justice reform advocates worry the campaign and others like it could help perpetuate mass incarceration.

The argument: If a judge is recalled because he wasn’t punitive enough, that could signal to other judges that they should be more punitive, and not just in cases involving sexual assault or domestic violence.

There’s a bit of judicial arithmetic here: Judges tend to get into trouble if a sentence is too short — the sentence itself could spark outrage, or the early release of an inmate may lead to trouble for the judge if the ex-inmate goes on to commit another crime. Meanwhile, a stringent sentence will rarely get any attention because people are simply much less likely to empathize with the perpetrator of a crime. As Pfaff said, “Being ‘tough on crime’ remains free for judges.”

If this applies across the board, more punitive sentences could disproportionately impact poor, minority groups, since poor minorities are disproportionately likely to be arrested and incarcerated.

Dauber has shot back at this criticism by pointing out that it is not the campaign’s goal to expand mass incarceration. The recall campaign opposes mandatory minimums, which are harsh sentences that, according to an analysis by the National Research Council, helped foster mass incarceration.

“Our campaign does not support mandatory minimums,” Dauber said, including the law that the state passed in response to the Turner trial. She went a step further, arguing that “opposition to mandatory minimums means that you should support the recall.”

Dauber’s argument: If judges don’t use their discretion properly, legislators will feel compelled to pass more mandatory minimums. This is part of the reason past mandatory minimums occurred — lawmakers felt that judges were generally too lenient on drug and violent offenses and passed mandatory minimums to counteract that leniency.

In fact, Dauber claimed, this is what happened in the Turner case: After Persky’s sentence drew so much negative publicity, California lawmakers passed new mandatory minimums — mandating prison time for cases similar to Turner’s — to try to ensure that judges can’t do what Perksy did ever again.

Still, Dauber said that the recall campaign has tried to focus specifically on Persky to avoid potentially sending a broader message to the criminal justice system — and perpetuating a system of mass incarceration that she and other supporters of the campaign oppose.

“We have extremely narrowly and conscientiously messaged and discussed this campaign as being about one judge who does not take sexual violence and violence against women seriously and favors elite, privileged perpetrators,” Dauber said. “We are progressives who support criminal justice reform. But there has to be space to talk about justice for women.”

Pfaff has a different take: The response to Turner’s sentence “shows a lack of imagination among progressives. We can and I do suspect that we probably under-punish sexual assault relative to comparable crimes that don’t involve sexual victimization.”

“But,” he added, “there are two ways to respond to that. One way to respond to is to say, ‘Okay, let’s make the sentence equal by punishing everybody less.’ Or, ‘Let’s make this equal by punishing everyone more.’ And I think the current case shows just how deeply ingrained, even among people who identify themselves as very progressive, it is — [the idea] that the only way to reach parity is to ratchet things up.”

Regardless of intent, the recall really could send a broader message

Even if it’s not the recall campaign’s goal to make judges more punitive across the board, that could be the ultimate outcome of a successful recall effort. With the recall underway, there have been multiple reports of judges watching Persky’s fate closely to see what it means for them.

We’ve seen this kind of thing before. It was public outrage over rising crime in the 1960s through the early ’90s that led to mass incarceration in the first place — giving not just lawmakers and prosecutors a reason to get “tough on crime,” but judges too.

Even if this only applies to violent cases like Turner’s, that would still perpetuate mass incarceration. Although much of the public believes that mass incarceration is a result of harsher punishments for low-level crimes, the reality is that the bulk of incarceration is in fact for violent crimes.

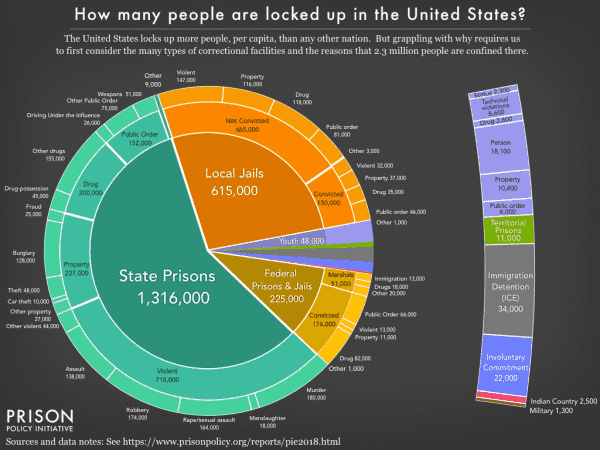

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, around 21 percent of people in jail or prison are there for a drug crime. About 42 percent of people in jail or prison are there for violent crimes — making violent offenses the single biggest driver of incarceration out of all offense categories.

There are ways to bring down the incarceration rate, even by pulling back punishments for violent offenses, without causing more crime. For one, the data suggests that people actually age out of crime — they’re more likely to commit a crime in their late teens or early 20s than they are in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and so on. So letting people out of prison 10 or 20 years down the line — instead of 40 or 50 years, or never — likely wouldn’t pose a threat to public safety.

One reason to do this: Incarceration is a pretty inefficient way to keep the public safe. A 2015 review of the research by the Brennan Center for Justice estimated that more incarceration — and its abilities to incapacitate or deter criminals — explained about 0 to 7 percent of the crime drop since the 1990s, though other researchers estimate it drove 10 to 25 percent of the crime drop since the ’90s.

Another review of the research, published in 2017, led researcher David Roodman at the Open Philanthropy Project to conclude that “tougher sentences hardly deter crime, and that while imprisoning people temporarily stops them from committing crime outside prison walls, it also tends to increase their criminality after release.”

To that last point, the National Institute of Justice declared in 2016, “Research has found evidence that prison can exacerbate, not reduce, recidivism. Prisons themselves may be schools for learning to commit crimes.”

The research suggests that to the extent that incarceration does deter crime, it’s about certainty, not severity, of incarceration. A 2010 review of the research by the Sentencing Project, for example, pointed to a study by the Institute of Criminology at Cambridge University in 1999 that concluded that “the studies reviewed do not provide a basis for inferring that increasing the severity of sentences generally is capable of enhancing deterrent effects,” and that macro-level studies reviewed by the researchers found that an increased likelihood of apprehension and punishment — certainty — was linked to falling crime rates.

This suggests that if the justice system is to prevent more cases of sexual assault, it will need to punish offenders more consistently. The system is currently doing an awful job at that: According to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN), for every 1,000 rapes, 993 will go unpunished.

Changing this will require some policy changes. More police departments could start sex crimes divisions that focus solely on sexual assault cases, and legislators could enact more funding for the training and oversight required to make this work. Ybos of People for the Enforcement of Rape Laws argued that getting police to focus less on low-level offenses — perhaps by decriminalizing drugs — could also get them to focus more on serious crimes.

But she argued that much of the change will need to go deeper — fundamentally altering the culture of law enforcement to simply take sexual assault cases much more seriously.

“I know that it’s a cathartic thing for some people to point to a piece of legislation to fix a problem,” Ybos said. “But that’s not always the right way to tackle a problem.”

Sourse: vox.com