Democrats are looking to come together as a unified party to beat President Donald Trump. But first they’re looking at a bitter, divisive debate about a subject most in the party would rather duck: Israel.

In recent decades, including under President Barack Obama, Democrats largely endorsed a bipartisan “pro-Israel” consensus that meant lending Israel both material and rhetorical support, despite some significant tensions beneath the surface and despite complaints around the world about Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians.

But that’s changing. It’s changing because Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has become increasingly comfortable with the idea of a strict partisan alignment with the Republican Party, even though American Jews vote overwhelmingly for Democrats.

And it’s changing because a rising tide of progressive politicians want to challenge a consensus among Democratic Party elites, a consensus that no longer reflects the views of Democratic voters.

The change is set to emerge at the top level of American politics over the course of the 2020 presidential campaign. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) broke significant taboos around this issue in 2016 with his pointed, strident criticism of the Netanyahu government. And looking ahead to 2020, he’s charted a break with past Democratic administrations by signaling a willingness to impose real consequences on Israel if it doesn’t change course on the occupation — even telling the Intercept’s Mehdi Hassan in a September 2017 interview that cuts in US financial aid and arms sales could be on the table.

The dynamics of the 2020 race for the party’s nomination will likely make Israel an even bigger issue. Sanders has retooled his team to be able to make a more robust argument on foreign policy, and with the differences between Sanders and the field on domestic topics narrowed, national security offers a big opportunity to reopen a gap between the insurgency and the establishment.

That’s a bigger argument than Israel, but Israel in particular is an area where there’s a discernible wedge between party leadership and the rank-and-file, and it’s an area where a Jewish leftist like Sanders has the opportunity to make a unique contribution.

Rashida Tlaib vs. Eliot Engel

A first glimpse of this coming clash came from an early December announcement by Rashida Tlaib, a Michigan Democrat newly elected to the House. She planned to skip the traditional AIPAC-funded junket to Israel, and instead wanted to organize her own congressional tour that would visit the West Bank and witness the occupation first hand.

AIPAC, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, is a lobby group and informal campaign finance bundler, that serves as the custodian of the pro-Israel consensus — at least nominally supportive of a two-state solution, but fundamentally on Israel’s side in every particular point of dispute.

“I want us to see that segregation and how that has really harmed us being able to achieve real peace in that region,” Tlaib — whose family is Palestinian — told the Intercept in an interview. “I don’t think AIPAC provides a real, fair lens into this issue. It’s one-sided. … [They] have these lavish trips to Israel, but they don’t show the side that I know is real, which is what’s happening to my grandmother and what’s happening to my family there.”

In the same interview, Tlaib said she personally supports the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement that proposes to target Israel with the kind of tactics that were used against apartheid in South Africa.

The vast majority of Democrats (including Sanders, to be clear) reject BDS, but Ilhan Omar, another new House Democrat, is also a BDS supporter and has so far been a more trenchant critic of Israel than Tlaib. Omar was recently rebuked by her colleagues for her allegation that congressional support for Israel is “all about the Benjamins.” But despite apologizing for those comments, she clearly has no intention of backing down from her criticisms of US foreign policy, as seen in her grilling of Elliott Abrams, a veteran foreign policy hawk, earlier this month.

These are outlier voices in a House caucus that is primarily composed of people who don’t have strong opinions about foreign policy and want to avoid the political controversy.

But on the other end of the spectrum, as Peter Beinart observed in a December 5 column, was a post-election panel at the Israeli-American Council featuring incoming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, and Haim Saban. Saban is a major Democratic Party donor (and patron of DC foreign policy think tanks) known for his hawkish views on Middle East policy, like the notion that rather than negotiate with Iran he “would bomb the living daylights out of these sons of bitches.”

Pelosi reassured Saban that he had nothing to worry about from House Democrats because “you couldn’t have two stronger supporters of Israel” than Eliot Engel and Nita Loewy, who will chair the House Foreign Relations and Appropriations committees respectively.

What she means by that is that both Engel and Loewy were among the small minority of congressional Democrats who are so committed to the Israeli party line that they bucked the Obama administration to oppose his signature diplomatic breakthrough with Iran. So did Schumer, the Democrats’ leader in the Senate. And so did Bob Menendez, the New Jersey Democrat who serves as the party’s top-ranked member of the Foreign Relations Committee.

In other words, the picture Pelosi was painting isn’t wrong. If you’re a mega-donor with a strong interest in hawkish Israel policies, you can rest assured that the commanding heights of foreign policymaking among congressional Democrats are held by hawks with outlier views that point in the opposite direction of Tlaib and Omar.

Pelosi, meanwhile, certainly wasn’t going to buck Obama on the Iran deal. But her priority as party leader is papering over disagreements and keeping divisive issues off the agenda. But in a crowded 2020 primary field, papering over disagreements isn’t in everyone’s interests.

Bernie Sanders broke taboos on Israel

Because Sanders’s 2016 presidential campaign was initially conceived as a protest campaign aimed at drawing attention to issues, it lacked anything resembling the normal effort to put together a coherent foreign policy message. The idea was to win a chance to get some media coverage for things like Medicare-for-all and free college.

But as his campaign caught a certain amount of fire, several of his best moments on the trail were focused on foreign policy.

That started with Iraq. Clinton was running as the de facto successor to Obama, who remained (and remains) extremely popular with rank-and-file Democrats. But Obama beat Clinton in the 2008 primary largely by emphasizing their differing views on the invasion of Iraq. Sanders went back to his well repeatedly, casting himself as the mainstream Democrat, and Clinton as the outlier hawk.

Sanders also scored points over Clinton’s lavish praise of war criminal Henry Kissinger and vowed to carry forward the logic of Obama’s Iran policy and seek normalization of relations with Tehran, while Clinton aimed to reassure Israel and the Gulf states that there was no broader US-Iran rapprochement in the works.

Sanders also shattered taboos on Israel, not so much by breaking brand-new policy ground — the support for a two-state solution, the notion that Israel has a right to defend itself, etc. were not especially novel — as by the frankness of his tone.

“As somebody who is 100 percent pro-Israel, in the long run,” Sanders said at one point, “we are going to have to treat the Palestinian people with respect and dignity.” He later followed up with the observation that “there comes a time when, if we pursue justice and peace, we are going to have to say that Netanyahu is not right all of the time.”

The Obama administration, of course, did not think Netanyahu was right all of the time. But they normally went out of their way to publicly downplay conflict and present a united face. Clinton’s public take on all of this was, in essence, to blame Obama and promise to build a stronger personal relationship with Netanyahu.

Sanders was taking the opposite approach, arguing that Israel was responsible for the decline in the US-Israel relationship and pushing for America to be firmer in its line and more publicly critical of Israel on the Palestinian issue, and less deferential to Israel on broader regional issues.

Foreign policy ultimately proved to be a sideshow in the 2016 campaign, and Sanders didn’t really do much to present a big vision on the topic. But — especially since Sanders is Jewish — these arguments on Israel were a breakthrough moment for liberal American Jews who’ve been frustrated with the direction Netanyahu has taken Israel and with American Jewish institutions’ inclination to go along.

Sanders’s campaign was also one of the first to directly court Muslim voters in the Midwest, which helped power his surprise victory in the Michigan primary and led to both Omar and Tlaib scoring the endorsements of Sanders’s Our Revolution political organization in 2018.

And he’s developing a bigger and more coherent message.

Sanders has a foreign policy now

In 2016, Bernie had occasional jabs on national security topics to throw at Clinton, but he didn’t really have much in the way of a national security message. He was sharp in his rehashing of Cold War arguments from the 1970s and 1980s, but fuzzy on topics like Syria and ISIS that didn’t connect in a clear way to his larger ideological project.

It was fundamentally a protest campaign that wasn’t really focused on the practical reality that all presidents end up spending a huge share of their time on national security issues, where the presidential role is much larger relative to Congress than it is on domestic policy.

Over the past two years, though, that’s begun to change.

Shortly after the 2016 election, Sanders hired a foreign policy staffer — Matt Duss, formerly of the Foundation for Middle East Peace and the Center for American Progress (CAP) — even though he doesn’t sit on the Senate’s foreign affairs or armed services committees.

This has helped Sanders weld some of his various ideas together into a coherent pitch that paints Trump as the US manifestation of a global movement toward authoritarianism that includes not just Russian President Vladimir Putin and the usual suspects of the populist anti-immigration right, but also traditional US allies like Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

“Interestingly,” Sanders observed in an October speech to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “many of these leaders are also deeply connected to a network of multi-billionaire oligarchs who see the world as their economic plaything.”

Duss linked back to the speech in a late December tweet, noting Netanyahu’s efforts to forge an alliance with Brazil’s newly elected far-right president Jair Bolsonaro.

Sanders’s vision has much more in its scope than Israel. The main objectives of Sanders’s speech are to try to demonstrate the global relevance of his class-first approach to politics and to bring himself into better alignment with the prevailing anti-Putin sentiment in the Democratic Party after fumbling the issue earlier.

But the inclusion of Netanyahu in the axis of authoritarians is a striking provocation, and a deliberate one.

Palestinian rights is a passionate topic for Duss — who, full

Sanders’s campaign manager, Faiz Shakir, hired Duss at CAP largely to push the envelope on this topic and was instrumental even before the launch of the campaign in bringing Duss onto Bernie’s team.

And because Sanders is Jewish — he even lived on a socialist kibbutz for a time in 1963 — he has a personal connection to the Israel issue that candidates typically lack, as well as a certain credibility to go further in criticisms of the Jewish state than many gentiles would typically be comfortable doing. And the voting public may be eager to hear that.

The politics of Israel have shifted

One of the many things that happened in the 2016 campaign is that Trump revealed the elite consensus in favor of free trade in the Republican Party to have relatively little grassroots support.

Somewhat similarly, the broad “pro-Israel” posture of Democratic elected officials appears to be somewhat out of touch with the underlying views of the rank-and-file.

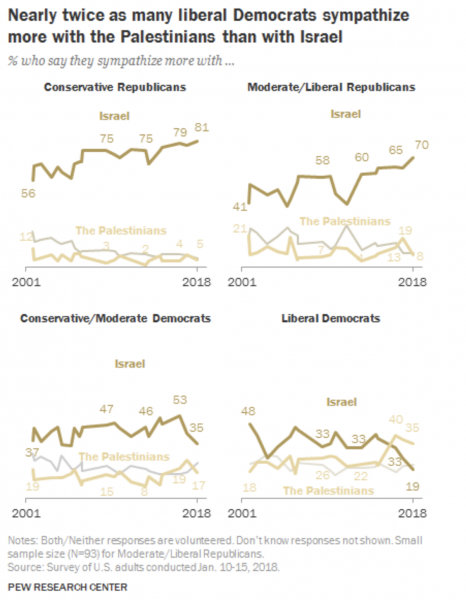

According to Pew Research Center polling, as Republicans have become increasingly pro-Israel in their views, Democrats — especially self-identified liberals — have become more sympathetic to the plight of the Palestinians, even as few Democratic elected officials have openly talked in this way.

Some of that is due to a change in the Democratic Party. The party includes more Muslims now, as well as a larger share of nonwhite Americans, for whom the Palestinians’ view of the conflict as an extension of European imperialism may seem more compelling.

The party has also become markedly more secular, substantially reducing the number of Democrats likely to embrace biblically-based arguments asserting Jewish rights to Israel. Last but by no means least, the experience of America’s post-9/11 wars has generally soured progressive Democrats on the kind of hawkish policies that are associated with Israel.

But arguably the larger shift has been in Israel itself, where the domestic peace camp suffered political collapse after a wave of violence known as the Second Intifada and the Netanyahu administration — more worried about its right flank than its left — has positioned Israel in a very different way than its predecessors.

While prior Israeli governments were very solicitous of diaspora Jewish opinion, especially in the United States, Netanyahu felt comfortable clearly aligning himself and his government with the Republican Party, even as American Jews overwhelmingly voted for Democrats.

That gave him the strategic flexibility to push back against the Obama administration not just on questions directly related to Israel, but on broader regional strategy with regard to Iran and Syria as well. In effect, Netanyahu raised the bar for what’s required to count as a “pro-Israel” politician in the Israeli government’s eyes, ensuring that mainstream Democrats like Obama would fail the test.

That, paired with relentless settlement expansions, has helped undermine Israel’s image with liberal American Jews and with liberals more broadly, creating space for more robust critiques than Obama ever offered.

This in turn feeds back into domestic politics throughout the West. While most American Jews put their trust in cosmopolitanism to safeguard our interests as a small minority group, Netanyahu has made common cause with nationalist politicians ranging from Trump to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. To European and American Islamophobes, Israel seems like a natural ally, while to American Jews, nationalist backlash politics seems like a natural enemy.

So far, Netanyahu’s political repositioning of Israel has worked rather well. Ten or fifteen years ago, it was fashionable for liberal Zionists to predict that failure to achieve a two-state solution would rapidly lead to Israel’s international isolation. That simply hasn’t happened.

Shared antipathy to Iran has brought Israel closer than ever to the Gulf monarchies, while the tactical alliance with evangelical Christians in the United States and the European far right gives Israel friends who don’t feel compelled to even pay lip service to Palestinian rights.

The Democratic Party’s base, however, increasingly sympathizes with the Palestinians’ plight, even though few national leaders have been willing to speak directly to the issue.

The coming storm

Foreign policy issues, of course, normally play a secondary role at best in American politics. And the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is just one rather small corner of the foreign policy realm.

That said, since foreign affairs are the domain in which presidents have the most autonomy from Congress, it’s arguably the space where the differences between the candidates are most significant. For Sanders, his willingness to go further in his criticism of Israel than his rivals is a lever into a broader argument — on America’s relationship with brutal Gulf dictators, hypocrisy in invocations of democracy and human rights as a foreign policy objective, and the bizarrely entrenched bipartisan consensus on US posture in the Middle East that has persisted across multiple failed military adventures.

In an era when many of Sanders’s distinctive policy proposals from the 2016 campaign are no longer so distinctive, it’s also a good way for him to distinguish himself from the rest of the field.

While Sanders was a relative lightweight on world affairs relative to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, he at this point has more of a profile on foreign policy than anyone else in the race save potential candidate Joe Biden — an Iraq War proponent whom Sanders would be happy to define himself against.

Sanders’s entire profile in politics over the past five years has been defined at least as much by efforts to reshape the boundaries of political debate as it has by a concrete political program. And there’s probably no area of public policy where the official debate in Washington has been more constrained than Israel.

Opening it up for a robust argument is totally counterproductive to short-term Democratic Party political goals, but that’s not really the kind of thing he cares about. It’s an issue where his voice could make a unique contribution to the debate and where a large minority of the public — likely including most rank-and-file Democrats — agrees more with his point of view than with the party establishment.

And that should make them very afraid.

Sourse: vox.com