President Donald Trump seems convinced that there is a scary conspiracy lurking in the protests for racial justice sweeping the nation: that antifa, a militant left-wing anarchist movement, is taking advantage of the demonstrations to burn the country down.

Over the past week, he has blamed looting on antifa in tweets, fundraising emails, and public appearances. He has used them to cast the protest movement as a fundamentally violent affair, claiming in a Monday address that “our nation has been gripped by professional anarchists, looters, criminals, antifa and others.” He has repeatedly vowed to officially label antifa a terrorist group, putting them on a federal list alongside al-Qaeda and ISIS.

But antifa (pronounced ahn-TEE-fah or anty-fah) is nothing like those terrorist groups. It is not a unified organization, but rather a loose ideological label for a subset of left-wing radicals who believe in using street-level force to prevent the rise of what they see as fascist movements. It is a kind of anarchist alternative to the police that originally took root in America’s punk scene, without any kind of national command and control structure.

These young brawlers — often scary-looking, wearing all-black clothes, when caught on camera — serve as a perfect foil for a president and a conservative movement looking to cast the overwhelmingly peaceful participants in protests over George Floyd’s death and police brutality as a group of violent thugs.

While there is undoubtedly an antifa presence at some of the recent protests, there is no reason to believe that antifa is responsible for their (occasional) turns toward violence. Internal FBI assessments and protest-related court documents tell a consistent story: Antifa members are not responsible for the unrest.

The real antifa is quite complex. Tracing their ideas back to interwar anti-fascists in Europe, the movement rocketed to public prominence as a left-wing foil to the alt-right — playing a notable role in the protests against Trump’s inauguration and in counter-protests against the white nationalist march in Charlottesville, Virginia. Their activity, both violent and non-violent, arguably helped curtail the spread of the alt-right; there are also clear examples of them crossing the line, including indefensible physical assaults on journalists.

But the “antifa” discussed in the president’s tweets and on Fox News bears little resemblance to this morally gray reality. They are a trumped-up boogeyman for the conservative movement, a totem used to justify their violent “law-and-order” approach to legitimate demonstrations demanding racial justice.

Where antifa comes from — and what it believes

Antifa’s origin story begins in the 1930s, in two different European countries: Germany and the United Kingdom.

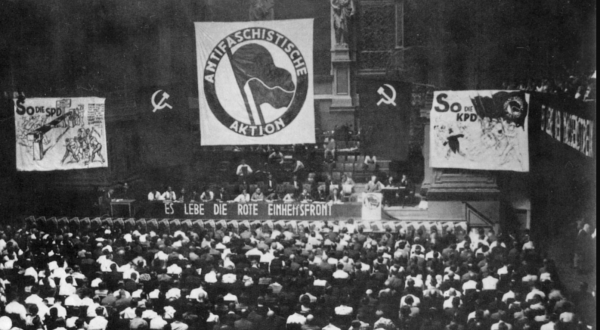

In 1932, the Communist Party of Germany founded an organization dedicated to opposing the rise of fascism called Antifaschistische Aktion — abbreviated, at times, as antifa. The group engaged in a series of direct actions to challenge the Nazis, including street brawls, but were forcibly dissolved after Hitler’s rise to power.

The British experience was quite different. In 1936, the British Union of Fascists — a political movement with real electoral support, but not nearly as powerful as the 1932 Nazis — attempted to lead a march through London’s heavily Jewish East End. Thousands of Jews and left-wing activists attacked the fascists and their police escorts, raining homemade bombs and rocks down on the parade. The BUF forces retreated; the leftists celebrated victory in what’s now remembered as “the Battle of Cable Street.”

While Antifaschistische Aktion was too late to stop the Nazis with force, modern antifa sees the Battle of Cable Street as proof that fascist movements can be defeated before they gain popularity if they’re forcibly blocked from appearing in public. They call this “preemptive” or “anticipatory” self-defense: Since fascists want to use force against you eventually, you’re justified in using it first.

This interpretation could be true, but it’s certainly debatable. One could argue that street brawling helped the Nazis more than it hurt them; some evidence suggests that Cable Street led to anti-Semitic reprisals and made the British public more sympathetic to the BUF.

Regardless, this “violence works” historical narrative is at the core of antifa’s ideology today. They deeply believe that the different paths of Germany and Britain in the interwar period proved the need to confront fascism with force.

“Self-defense, which often entails violence, is an indispensable part of [antifa] politics,” says Mark Bray, a historian of antifa at Rutgers University. “They believe, and I think rightly so, that fascism and proximate far-right politics are inherently aggressive — and that, if you’re not ready to defend yourself in advance, it may be too late when the time comes.”

It’s probably not a coincidence that the modern incarnation of antifa also has its roots in the UK and Germany. This time, the crucial period is the 1980s.

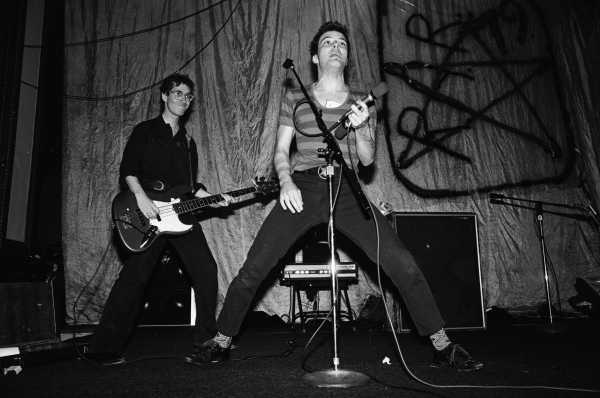

Back then, West Germany was dealing with a resurgence in neo-Nazi sentiment and activity. The punk rock scene in Britain, an aggressive subculture with anarchist political leanings, was similarly becoming a recruiting space for white nationalists tapping into anger and disaffection common among British punks. In both countries, activists took matters into their own hands — fighting neo-Nazis on the ground in order to prevent what they worried could be a replay of the 1930s.

One UK-based group, called Anti-Fascist Action in a direct nod to the 1930s German group, became the inspiration for a similar organization in American spaces. Called Anti-Racist Action, on the theory that this language makes more sense in an American political context, it became an organizing banner for punks (at first) who wanted to boot neo-Nazi skinheads from their own scene. In the 2000s and 2010s, the label Anti-Racist Action gave away to the now-popular antifa.

Stanislav Vysotsky, a sociologist at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater who has done extensive interviews with antifa members, describes them patrolling neighborhoods and guarding the doors at punk shows to prevent Nazis from entering. When these tactics fail, they resort to violence.

“Fascists are first aggressively confronted about their presence and ordered to leave by large group of people (in many cases, the entirety of the venue),” he writes in a 2015 paper. “If fascists do not leave when confronted, force is often used to eject them from the space, either in the form of physical removal or through a violent clash between them and anti-fascists.”

Vysotsky sees this as a kind of “anarchist policing.” In the punk subculture, people don’t like or trust the police: Armed agents of the state are as un-punk as you can get. But neo-Nazi skinheads won’t leave concerts politely when told; some kind of counter-force is required to keep punk shows safe for people of color and Jews who want to attend. Hence, the need for loose groups of anti-fascists brawlers willing to kick them out.

Antifa might have remained little more than a facet of America’s marginal punk scene, unknown to the vast majority of Americans, if it weren’t for the rise of Donald Trump and the alt-right in 2015.

Trump’s victory was accompanied by the growth of a kind of more electorally-minded white nationalist politics, an organized effort to win power and influence by riding the soon-to-be president’s coattails. This so-called “alt-right,” personified by the allegedly “dapper” white nationalist Richard Spencer, organized online and staged increasingly public real-world demonstrations.

This is not something antifa could abide. Taking lessons from the forebears in the 1930s and 1980s, they started organizing to stop the modern far-right before it could really get started.

“As fascist and far-right movements and personalities publicly supported Trump’s campaign and presidency, antifascist opposition mobilized against them,” Vysotsky tells me. “These mobilizations became more commonplace after his inauguration as fascists organized rallies under the guise of support for Donald Trump and his agenda which were met with strong, sometimes violent opposition.”

As the alt-right became more prominent, so did their more radical left-wing opponents — a degree of notoriety that these “anarchist police” simply were not prepared for.

How antifa became Trump’s boogeyman

Antifa does a lot more than merely brawl with far-right activists. Members of antifa groups do more conventional activism, flyer campaigns, and community organizing, on behalf of anti-racist and anti-white nationalist causes. This type of work, according to Bray, makes up the “vast majority” of antifa activity.

It’s also a bit imprecise to describe “antifa” as doing anything uniformly. Because of its origins in punk scenes, the movement is highly decentralized and localized. Some of it takes place through specific local organizations, like Portland’s Rose City Antifa, but there’s no national umbrella leadership. Some of what we call “antifa” activity is really just random kids with no formal affiliation with their local antifa group; they call themselves “antifa” because they think fascism is bad and it’s cool to fight against it.

But three incidents in the Trump years led to antifa’s more violent activities becoming the defining element of the movement in the public imagination: the protests during Trump’s inauguration, the white nationalist march in Charlottesville, and the attack on a conservative journalist in Portland. They turned antifa into a hero for part of the left — and a powerful villain for the right.

During Trump’s inauguration, a video of Richard Spencer getting punched in the face by a black-clad activist (who may or may not have been a formal antifa activist) went mega-viral. Remixes of the video set to songs like “My Heart Will Go On” got thousands of shares and retweets, becoming an iconic early image of resistance to the new regime among certain segments of left-wing social media.

The inauguration demonstrations and Spencer incident led to a surge in interest in antifa: In January 2017, NYC Antifa’s Twitter following increased by roughly a factor of four. But it also associated the group with the broader rioting and property destruction that marked the inauguration demonstrations, leading to what Vysotsky describes as “a conflation of black bloc tactics [like property destruction], anarchist activism, and antifascism, especially within conservative and far-right discourse.”

There’s a large universe of radical left-wing groups in the United States, and antifa is by no means the only one to engage in street-level violence. That can make it very tricky to identify whether any individual example of violence, even violence directed at far-right activists, can be linked to antifa per se.

But during the Trump era, where fears of an authoritarian turn in the United States have risen to dramatic levels on the left, antifa has come to occupy the most prominent place. The 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville is probably the biggest reason why.

A major white nationalist rally, replete with terrifying imagery and chants of “Jews will not replace us,” is exactly the kind of open far-right organizing that antifa believes needs to be stopped in order to prevent fascism from rising any further. Antifa groups had a significant presence at the rally, often interposing themselves between armed right-wingers and counterprotesters; Princeton professor Cornell West, who was on the ground with a band of clergy members, claims that “they [antifa] saved our lives.”

In the months following Charlottesville, antifa groups hounded white nationalists, regularly appearing at and disrupting their events. In March 2018, Richard Spencer canceled the remaining stops on his college speaking tour, releasing a tearful video in which he declares that “antifa is winning.”

Some saw this as evidence that violence worked to suppress the alt-right; others wondered if the movement’s less violent activities, like publicly identifying white nationalist activists, may have played a bigger role. Regardless, the alt-right has undeniably declined in influence since then — though other, more nakedly violent far-right movements have risen in its wake.

The confrontation with the alt-right, a white nationalist movement that sought to gain power through electoral means, was tailor-made for antifa’s approach. The alt-right directly aped the strategy of 1930s fascist movements that antifa members believe their tactics are uniquely equipped to defeat. Antifa had an opportunity to put their theory of preemptive self-defense to work; Spencer’s tour cancellation is evidence that it worked.

But even if you buy this interpretation, there’s an obvious problem with antifa’s approach: It’s not clear who, exactly, counts as a “fascist.”

Individual antifa organizations and even activists take it upon themselves to identify the fascists and attack them accordingly; there’s no system of national accountability, nor any “Antifa Central” that can disavow the actions of specific activists as ones of rogue actors. The closest thing is the Torch Antifa network, a national umbrella group for the movement that facilitates coordination between local groups but lacks command-and-control powers.

As a result, what any antifa group or member does can be spun as indicative of the group as a whole, and there’s no antifa PR agency to dispute it or reshape the narrative. This is essentially how antifa became public enemy number one in the second half of Trump’s term in office.

In late June 2019, the far-right Proud Boys street fighting group held a rally in Portland, Oregon. Left-wing groups, including Portland’s Rose City Antifa, put together a counterprotest — whose attendees clashed with the Proud Boys. The most notable instance of violence had nothing to do with the Proud Boys: It was an attack by counterprotesters on the conservative journalist Andy Ngo that sent him to the hospital.

In footage captured by Portland-based reporter Jim Ryan, crowd members douse Ngo in milkshake, punch him, and yell at him. It looked a lot like an unprovoked, unjustified, reprehensible assault on a journalist by antifa.

Ngo is a conservative provocateur sympathizer who has worked with militant right-wing groups; he seems to delight in antagonizing antifa members and broadcasting the results. As reprehensible as this behavior is, it does not turn him into a legitimate target; whatever his ideology, he’s still a journalist. The footage of the attack spread widely, turning antifa into a major villain in the Republican Party and conservative media. House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy condemned the group, as did Sen. Ted Cruz.

About a month after the attack on Ngo, Trump tweeted about antifa for the very first time — threatening, as he has recently, to label them a terrorist group:

Warning of dangerous far-left activism is a common staple of Republican and conservative political rhetoric; Fox News stoked panic about the New Black Panthers, a black nationalist group, early in Barack Obama’s first presidential term.

But antifa assumed a particularly outsized role in right-wing political discourse after Ngo, coming up again and again in complaints about the radical left. It was only natural that they ended up playing a starring role in the conservative narrative about the George Floyd protests.

Antifa, the current uprisings, and Trump’s empty threat to label them terrorists

After some of the George Floyd protests turned violent, the White House wasted no time in pinning the unrest on antifa.

Appearing on CNN’s State of the Nation, National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien flatly declared that “this is being driven by antifa.” Warning of “antifa radical militants who are using military tactics to kill and hurt and maim our police officers,” O’Brien announced that “we’re going to get to the bottom” of this nefarious antifa plot.

O’Brien offered no evidence for these inflammatory charges, and it doesn’t seem that very much exists.

While there’s some kind of antifa presence at some of the major protests, it’s very hard to attribute all of the violence to the movement. Not every person wearing all black and breaking windows is a member of their local antifa organization. And there’s very little evidence that antifa is responsible for a significant proportion of the looting.

“My conversations with law enforcement and intelligence officials in multiple US cities suggest that antifa played a minor role in violence,” Seth Jones, an expert on terrorism at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, writes. “The vast majority of looting appeared to come from local opportunists with no affiliation and no political objectives. Most were common criminals.”

A May 31 memo from the FBI’s Washington field office reported “no intelligence indicating Antifa involvement/presence” in violent activities in the nation’s capital. Not a single one of the first 22 protest-related indictments nationwide indicated that antifa played a role in looting or property destruction. An Associated Press review of 217 arrests in Minneapolis and DC found that “of those charged with such offenses as curfew violations, rioting and failure to obey law enforcement, only a handful appeared to have any affiliation with organized groups.”

The dearth of antifa-linked violence reflects the fact that the protests are generally quite peaceful — and that the number of actual antifa activists nationwide is quite small.

“Northern California and Oregon are two of the most active places for antifa in the US. At their biggest events they have like 200 people,” Bray, the Rutgers scholar says, says. “Yet you’re seeing things being burnt down in Arizona and Salt Lake City. That gives you a sense that this is much bigger than [antifa].”

This is not to excuse any acts of vandalism or violence by antifa members that are eventually uncovered. Even Bray, who’s generally sympathetic to antifa, thinks it’s “plausible” that some of the movement’s members are responsible for some of the property destruction or other disruptive activities during the demonstration.

But it’s one thing to say some members are doing this stuff — a “faction of a faction,” as Bray puts it — and another to argue, as O’Brien does, that antifa is behind the overall tumult. The former is a reasonable suspicion based on antifa’s track record, the latter a political move designed exclusively to provide moral justification for a police crackdown on peaceful protesters.

The Trump administration’s attacks on antifa do not actually reflect the reality on the ground or the minuscule “threat” from the group. Instead, they serve primarily to stigmatize the protests themselves — and justify harsh police responses.

Take, for example, Trump’s repeated vows to label antifa a terrorist organization. He cannot do this legally: The federal government maintains a list of foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs); while there are antifa activists outside the US, the domestic groups do not have any meaningful organizational linkages with them. There is no such thing as a domestic terrorism designation, and it would require an act by Congress to create one. The president’s proposal is, legally speaking, impossible.

But while Trump’s threat to label antifa a terrorist group may be toothless, it serves an important ideological function. It helps fuel the argument that violent radicals are the driving force behind the current wave of protests — that they are at their heart a kind of subversive force, rather than an expression of legitimate grievance, and can be put down as such. It is less an actual policy proposal than a rhetorical device aimed at giving the police and federal security services ideological cover.

We can then distinguish between antifa, the actual movement, and “antifa,” the thing that Trump has positioned as his enemy.

The actual antifa movement is very small and, by all accounts, ancillary to the main story of the current wave of protests. What we’re actually seeing right now is that a large portion of the country is fed up with the way police are treating black people. Protesters have taken to the streets in overwhelmingly, but not entirely, peaceful protests — and been attacked by police in response. There’s looting and burning, perhaps even some by antifa members, but virtually no real evidence reason to suggest that antifa violence is a significant problem.

But when Trump says “antifa,” he doesn’t really mean the actual local movements — which are far too small and marginal to pull off anything he’s accusing them of. The term has become a stand-in, a catch-all for demonstrators the government doesn’t like. Invocations of antifa are not references to anything that any individual antifa organization is doing, but rather a way of conjuring up a specter of violent leftism in order to justify a heavily militarized response.

Antifa exists, and is responsible for some acts of violence in recent years. “Antifa” as Trump imagines it only exists in the conservative mind — but could end up serving as justification for much more significant state violence down the line.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Sourse: vox.com