America could become the first country in the world to force tobacco companies to reengineer their products so they’ll be less addictive.

The Food and Drug Administration announced Thursday that it’s moving to put in a place a regulation that will set a maximum amount of nicotine cigarettes can have.

The FDA first discussed the measure last summer as part of its comprehensive new plan for tobacco and nicotine regulation. But today’s advance notice of proposed rulemaking is the first real step in initiating the long, bureaucratic process that would make the regulation a reality.

“We believe the public health benefits and the potential to save millions of lives, both in the near and long term, support this effort,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said in a statement.

Researchers who modeled the health impact of nicotine limits for a new paper in the New England Journal of Medicine showed the policy could help some 5 million adult smokers quit smoking within one year, and by 2100 prevent more than 33 million people from becoming regular smokers at all.

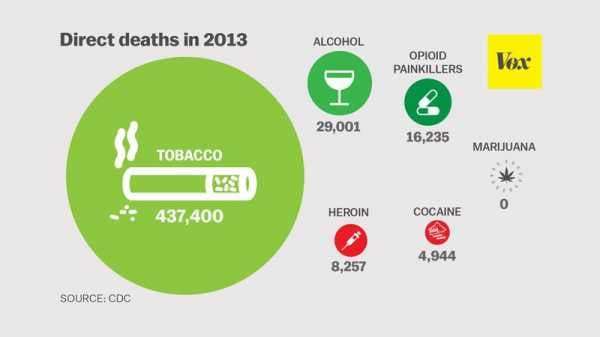

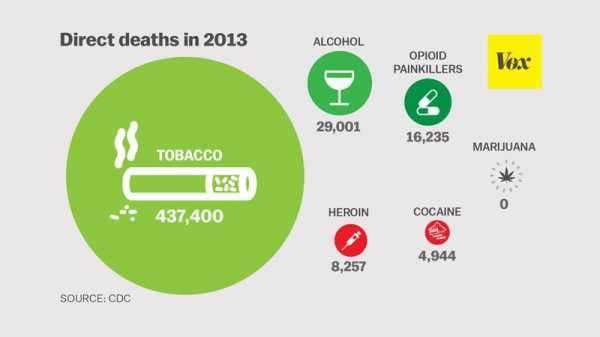

Cigarette use has been on a downward trajectory for decades in the US thanks to tobacco taxes, smoking bans, and public awareness campaigns. But smoking is still the leading cause of preventable disease and death in America, contributing to nearly half a million early deaths and more than $300 billion in health care expenditures and productivity losses every year.

According to the model, smoking rates could drop from 15 percent to as low as 1.4 percent, Gottlieb said. “All told, this framework could result in more than 8 million fewer tobacco-caused deaths through the end of the century — an undeniable public health benefit.”

“Cigarettes are as or more harmful, and as or more addictive, than they were 60 years ago, when people were using cigarettes without filters,” said University of Waterloo public health researcher David Hammond (who was not involved in the NEJM paper). “It’s a bizarre historical coincidence nothing has been done to change that fundamental equation.”

The proposed policy could change the equation — but it’s by no means a standard anti-smoking regulation; no other country has ever tried such a measure. So it’s a big deal the US is going first.

“If the US does this, and is successful, other countries will join in,” said David Liddell Ashley, the previous director of the office of science in the Center for Tobacco Products at FDA. “You will see a reduction in deaths from tobacco — tens of millions of people a year will no longer die from tobacco use.”

The news is also a reminder of America’s somewhat schizophrenic relationship with regulating smoking. Nicotine limits would be one of the most avant-garde tobacco policies in the world. And yet the US still lags behind many other countries — including low-income countries — on many other tobacco control basics.

How cutting nicotine could drive down smoking rates

Nicotine is the addictive substance in cigarettes. The chemical on its own isn’t harmful in most cases — it’s all the other chemicals and toxicants involved in smoking that kill people.

But the idea behind the FDA’s policy is that if you cut the amount of nicotine in cigarettes — through genetic engineering of tobacco plant or chemical extraction — to very low levels (between 0.3 and 0.5 milligrams per gram of tobacco filler), you make them less addictive or non-addictive, helping smokers quit or abstain from taking up the habit in the first place.

The approach is expected to work in two ways. We know longtime smokers in the US typically initiate the habit in their youth. So making cigarettes less addictive could also help keep young people from getting hooked on the products in the first place.

“The primary goal of [the new policy] is to cut it off at the knees in terms of smoking initiation,” Hammond summed up. If a 14-year-old tries a cigarette, there’s not going to be enough nicotine in the product to promote and sustain an addiction, for example.

The second way the policy could work is by helping established smokers who are already hooked on nicotine stop smoking. If the cigarettes on the market have lower levels of nicotine — not enough to get their fix — they have a greater incentive to turn to other noncombustible nicotine products, like e-cigarettes, which are widely believed to be less harmful than smoking.

One of the major concerns about the policy is the potential to foster a black market: If smokers can’t get the cigarettes they’re used to through normal channels, they may turn elsewhere.

But the beauty of the FDA policy is that it’s coming at a time when the agency is also working to get more noncombustible cigarette alternatives on to the market.

“For me, the big picture is that these two steps need to be looked at hand in glove,” said Michael Eriksen, dean of the school of public health at Georgia State University and a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Office on Smoking and Health. “One doesn’t work without the other. You need to make cigarettes and smoking combustible products less addictive, less appealing. At the same time, you need to make available safer alternatives for people addicted to nicotine who want to continue to use nicotine.”

The US still lags behind other countries on tobacco control

There are some very basic tobacco control measures that most developed countries have put in place but the US still hasn’t. As I’ve explained, these include graphic warning labels on the sides of cigarette packages and restricting the advertising of cigarettes elsewhere.

While more than 100 countries have already updated their cigarette packages to make them less appealing, the US hasn’t budged. In fact, America hasn’t updated its health warnings on packs since 1985. (A text-only surgeon general’s warning was introduced in 1966, but it hasn’t been updated in 33 years.)

What’s more, there are 180 countries that have ratified the United Nations’ Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which commits countries to require graphic warnings on packs and other anti-smoking regulations. The US isn’t one of those either, which means America doesn’t have to follow all the tobacco control policies other countries have promised to.

So while the new nicotine limiting policy is truly significant — if it’s not also blocked by tobacco companies — the US is still trailing behind other countries on these basic measures that have been proven to work.

“If you’re talking about leadership,” Hammond said, “taking a step back and looking at tobacco control policy, [this] raises more questions about why FDA hasn’t been able to ban ads in retail outlets [and update cigarette packaging]. If they are really worried about smoking initiation, they should get the ads out of there.”

This shouldn’t detract from the potential of the proposed rule, he added, but it does raise questions about the FDA’s inaction in other areas of tobacco control.

“The most important things that can be done to reduce the harm from smoking — [nicotine limits] would not be on that list,” Eriksen said. Instead, the list includes increasing the tobacco tax, clean indoor air laws, restrictions on ads and promotion if not outright bans, and graphic warning labels.

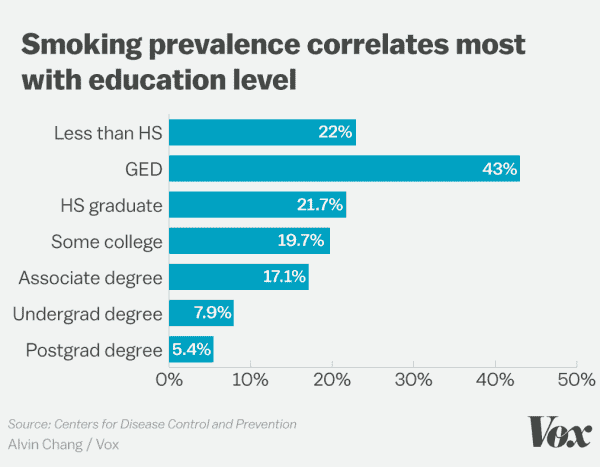

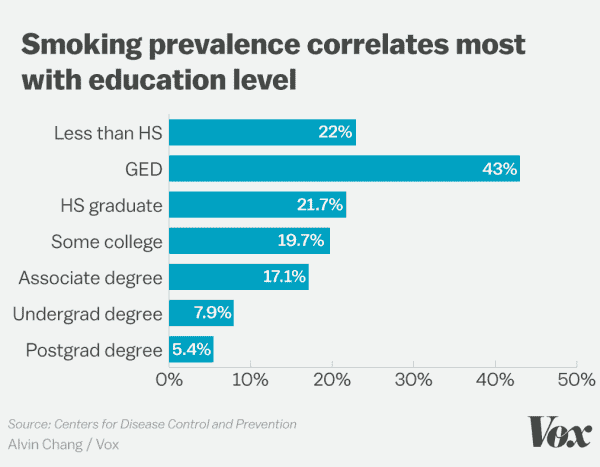

He also noted that smoking in America is heavily correlated with low education levels and mental health problems — a problem that often gets ignored. “This is a novel approach, but it has not been the bread and butter of tobacco control,” he said.

The regulation could take years to be enacted

The regulation, if enacted, will take a while to put in place. Today’s announcement of the proposed rulemaking simply invites stakeholders and the public to give input on a potential policy, including questions about what the limits on nicotine should look like, whether the policy should encompass other tobacco products, and any potential unintended consequences of curbing nicotine.

As a next step, the agency will issue a proposed rule based on that input and then it’ll need to pass the policy through at least half a dozen steps to get to the implementation stage.

There are nine steps in this regulatory process without any litigation, Eriksen said. He and others anticipate tobacco companies will try to fight the policy. “We’re talking about years, not months. We’re talking about maybe a decade.”

Still, noted Ashley, former director of the office of science in Center for Tobacco Products at the FDA, Commissioner Gottlieb’s enthusiasm for the policy and focus on tobacco control generally is a good sign it’ll move ahead. “From my experience, he would not be making the statements he is if there wasn’t support for this through the administration,” he said.

“I think this will have more impact than anything else FDA could do and maybe all of those things put together,” he said, adding that the research to date has shown low-nicotine cigarettes help smokers quit. “Taking nicotine out will not have an instant impact on smokers.”

Sourse: vox.com