Strict voter ID laws, now on the books in 10 states, have gotten a lot of attention over the past several years. Supporters argue that they’re necessary to stop voter fraud, particularly voter impersonation. But critics argue that the laws, by restricting voting, make it harder for minority voters in particular to cast a ballot.

But a new study suggests that the laws, which require certain IDs to vote, may do neither.

The study, from Enrico Cantoni at the University of Bologna and Vincent Pons at Harvard Business School, found that voter ID laws don’t decrease voter turnout, including that of minority voters. Nor do they have a detectable effect on voter fraud — which is extremely rare in the US, anyway.

The implication: Despite the legal and political battles over voter ID laws, they don’t really seem to do much of anything.

The researchers caution that their results “should be interpreted with caution” and that they “do not see our results as the last word on this matter — quite the opposite.” Still, the findings join a growing body of research that suggests voter ID laws have a much smaller effect than critics feared and proponents hoped.

Democrats argue that the laws discriminate against minority and younger voters who are more likely to vote for Democratic candidates, because they’re less likely to have the money, transportation means, and flexible work hours needed to obtain a required ID. Republicans, on the other hand, insist that the measures are meant only to protect against voter fraud, although in some cases they’ve admitted that the intent is to make it harder for some groups to vote.

The authors of the new study don’t view their findings as a go-ahead for passing more voter ID laws. Citing the laws’ apparent ineffectiveness against voter fraud, they argue the opposite: “This result weakens the case for adopting such laws in the first place.”

What the latest study found

The study drew on multiple sets of data to evaluate the impact of voter ID laws.

On voter turnout, the researchers drew on a data set from Catalist — which collects and sells voter registration and turnout records, as well as data for unregistered voters from data firms, retailers, marketing companies, and other commercial sources. The researchers say the Catalist database covers the vast majority of voting-age individuals.

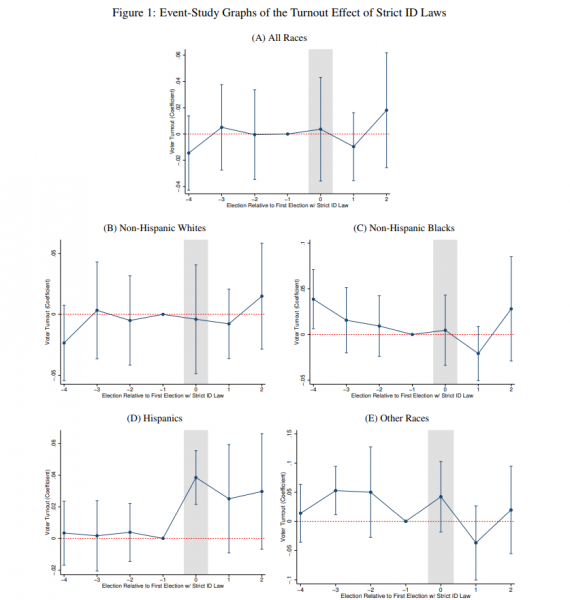

The researchers then looked at how the voter ID laws affected turnout and compared trends to states without voter ID laws from 2008 to 2016.

The results: Voter ID laws do not seem to decrease turnout, even when the data is broken down by race. This held when the data was analyzed in different ways, like evaluating only the effect of stricter laws that require an ID with a photo.

One possibility, the researchers acknowledge, is that voter ID laws do have some effect, but mobilization efforts against voter ID laws end up canceling it out — since, after all, these measures have become highly contentious among Democrats in particular.

So the researchers tried to account for that, using data for people’s self-reported contacts from campaigns, donations to candidates, political meeting attendance, use of campaign signs, and campaign volunteering, all of which would suggest voter mobilization.

There was no evidence that political mobilization went up significantly after voter ID laws.

“We cannot fully reject the possibility that mobilization against the laws alleviated direct negative effects — that would require evidence on additional outcomes such as people’s feelings — yet we do not find any sign of it in available data,” the researchers found.

Finally, the researchers turned to voter fraud. For this, they used two databases tracking voter fraud reported by the media and elsewhere — one from the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, and another from News21, a journalism project that the researchers described as “more liberal.” Their conclusion was straightforward: “We find no significant effect in either dataset.”

They also didn’t find a significant effect on perceptions of voter fraud — measured by how often people think voter fraud occurs and their beliefs that elections were fair.

Simply put, voter ID laws seem to have no detectable effect on voter fraud, real or perceived.

The researchers caution that their findings are not meant to be the final word. It’s possible that the results could be flawed — maybe the data sets for voter turnout are less complete than they believed, or the type of analysis they took on for this study isn’t the right model. The voter fraud databases in particular are, by their own admission, not comprehensive. Or maybe voter ID laws do have some effect, but the model the researchers used couldn’t detect it because it was just too small.

This is also a working paper, so it’s likely to be reevaluated as it goes through a review process.

Still, there’s other research to suggest that voter ID laws don’t have as much of an effect as people on both sides of the debate suggest.

Other research suggests voter ID laws have limited to no effect

It’s good to be skeptical of single studies with surprising findings, but previous reviews of the research on voter ID laws are in line with what Cantoni and Pons’s study found.

In 2017, Benjamin Highton, a political scientist at UC Davis, conducted the most thorough review of the research yet on voter ID laws. He tried to filter out the studies with weaker methodologies, putting more emphasis on those that were more rigorous. His conclusion: The better studies “generally find modest, if any, turnout effects of voter identification laws.”

In 2014, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) conducted a review on voter ID laws. Among the 10 studies it looked at, the results were mixed — five found no significant effect on turnout, one found increased turnout, and four found decreased turnout (between 1 and 4 percentage points). The GAO’s own study, looking at the effects of voter ID in Kansas and Tennessee, indicated that the laws may have decreased turnout by a few percentage points, with larger effects among younger, black, and newer potential voters.

Some caution is still warranted with these research reviews: Even if these laws have very modest effects — a decrease of 1 to 3 percentage points in voter turnout — that could still affect close elections. These kinds of elections are rare, but they can happen, and they can be important. For example, Democrat Heidi Heitkamp beat her Republican opponent, Rick Berg, by fewer than 3,000 votes, out of nearly 320,000, in 2012 to become a US senator for North Dakota.

And every study and review on this topic expresses a need for more research, indicating that this issue is far from settled.

Still, the overall research so far suggests that voter ID laws don’t have much, if any, effect on turnout. If true, these laws are not swinging the great majority of elections.

This may be surprising, given some of the reports about voter ID requirements in the past few years. A 2012 analysis, for example, found that as many as 758,000 registered voters in Pennsylvania didn’t have a photo ID issued by the state’s Transportation Department — suggesting that up to 9.2 percent of Pennsylvania voters may have been disenfranchised by a strict photo ID law.

But as Nate Cohn explained in the New York Times, this kind of figure is highly misleading. Citing a study for the North Carolina Board of Elections, Cohn wrote that “the true number of registered voters without photo identification is usually much lower than the statistics on registered voters without identification suggest.” The figure is just an estimate, “calculated by matching voter registration files with state ID databases.” But this method overestimates the number of voters without identification.

To the extent the figure is right, though, it misses another crucial point: People without IDs are less likely to vote in the first place. Based on the North Carolina study, voters who could be matched to a driver’s license — an ID, in other words — were more than 60 percent more likely to participate in the 2012 election.

Still, those few voters who may be denied the right to vote are more likely to be minorities and Democrats, based on previous studies on voting data. That’s a problem, but apparently not one that impacts most elections — given that other research, like Cantoni and Pons’s study or Highton’s review, suggests the overall impact of voter ID laws on voter turnout is small to nonexistent.

That doesn’t make voter ID laws okay — far from it

One reaction to this evidence is that it may justify voter ID laws. After all, if they don’t significantly reduce voter turnout, then what’s the harm if they can help combat voter fraud?

But as Cantoni and Pons noted in their study, the evidence suggests that voter ID laws have no significant effect on perceived or actual voter fraud.

That shouldn’t be surprising, because voter fraud is already incredibly uncommon in the US, especially the kind of fraud — voter impersonation — that ID requirements target.

Loyola Law School professor Justin Levitt studied voter impersonation. He found 35 total credible accusations between 2000 and 2014, constituting a few hundred ballots at most. During this 15-year period, more than 800 million ballots were cast in national general elections and hundreds of millions more were cast in primary, municipal, special, and other elections.

A 2012 investigation by the News21 journalism project looked at all kinds of voter fraud nationwide, including voter impersonation, people voting twice, vote buying, absentee fraud, and voter intimidation. It confirmed that voter impersonation was extremely rare, with just 10 credible cases.

But the other types of fraud weren’t common either: In total, the project uncovered 2,068 alleged election fraud cases from 2000 through part of 2012, covering a time span when more than 620 million votes were cast in national general elections alone. That represents about 0.000003 alleged cases of fraud for every vote cast, and 344 fraud cases per national general election, in each of which between 80 million and 135 million people voted. The number of fraudulent votes was a drop in the bucket.

What’s more, not all — maybe not even half — of these alleged fraud cases were credible, News21 found: “Of reported election-fraud allegations in the database whose resolution could be determined, 46 percent resulted in acquittals, dropped charges or decisions not to bring charges.”

So the problem that voter ID laws set out to fix isn’t really a problem that needs solving.

But maybe the goal of these kind of laws isn’t to combat voter fraud, but to suppress certain voters. As the New York Times reported, some Republicans have openly acknowledged that hurting Democratic voters is their goal.

One example, reported by William Wan for the Washington Post, regarding North Carolina’s court-rebuked voter ID law:

So despite claims that this is really about the integrity of elections, enough Republican supporters have slipped in moments of candor to validate Democrats’ suspicions — that this is about stifling the fundamental right to vote for minority constituents Republicans don’t typically win. No matter the real or perceived effect of voter ID laws, that intent is racist.

Fortunately, the research suggests that voter ID laws aren’t effective at suppressing voters, either.

Given the latest research, some conservatives are starting to push against more voter ID laws. Writing in the New York Times, conservative columnist Ross Douthat argued that Republicans should “step back and stand down” from voter ID laws.

He added, “The voter ID debate essentially involves Republicans whipping themselves into a panic over a problem that doesn’t meaningfully affect their chances of winning elections, and then passing laws that whip Democrats into a panic over a problem that also doesn’t meaningfully affect their chances of winning elections. So if the debate simply disappeared tomorrow, a source of distrust would vanish without either side losing ground.”

Sourse: vox.com