House />

House />

The 2018 midterms are shaping up to be a historic wave election. But even if Democrats win big in November, they may come out with fewer seats than the popular vote might suggest.

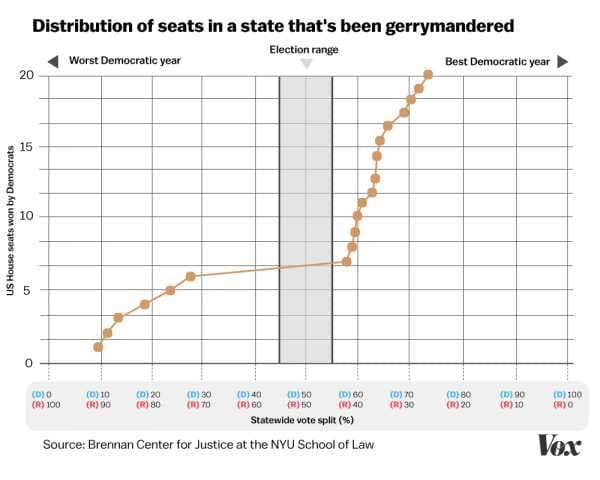

Blame extreme Republican gerrymandering. That’s according to a new report from the Brennan Center for Justice, which finds that Republicans have so effectively gerrymandered key states like Ohio, North Carolina, and Wisconsin that it could prevent Democrats from reclaiming the 24 seats they need to retake the House majority, even if they win the popular vote by the same margins they did in past wave elections, like 2006.

In recent weeks, Democrats have led the generic ballot by an average of 5.8 points. (That number has fluctuated in the past few months and will continue to fluctuate between now and November.) In 2006, they picked up 31 new seats in the House with 5.4 percentage points.

But with Republican-dominated congressional redistricting in 2011, Brennan Center researchers project Democrats are going to win far fewer seats — around 12 — even if they win by an 8.8-point margin in 2018. In today’s gerrymandered landscape, Brennan researchers estimate Democrats would have to win the popular vote by 11 points, something neither party has achieved in decades.

The report throws some cold water on the hype surrounding the 2018 wave. It’s not predicting that Democrats can’t take back the majority — just that Republican structural advantages will make it much more difficult to do so.

“What you have here is Republicans almost 10 years later reaping the benefits, just because of one big election cycle in 2010,” said Michael Li, a senior counsel who directs the center’s redistricting research and is one of the report authors, along with Laura Royden. “That’s a scary and undemocratic thing.”

Other experts don’t see the picture as quite so bleak.

“The Brennan Center’s conclusion that Democrats would need to win 11 percent more votes than Republicans is flawed,” said Dave Wasserman, an elections analyst and the US House editor of the Cook Political Report. Wasserman estimates Democrats need to win the popular vote by about 7 percent to clinch a slim majority.

In fact, as Wasserman points out, the electoral picture has gotten more favorable for Democrats leading up to 2018, given the fact that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court recently ruled the state’s congressional maps an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander and drew new, fairer ones.

“The Democrats’ gap between vote margin and seat margin has not been that wide in the past three elections that were held under lines that were less favorable to Democrats,” Wasserman told me, adding that Pennsylvania “was one of the biggest Republican redistricting advantages up until now.”

What Li and other experts are afraid of is that gerrymandering, far from going away, will be used by both parties to keep a hold on power long after they are politically popular. Essentially, this takes voting power away from voters and gives it to whichever party has the better map.

How Republicans could thwart a Democratic wave

To look at how Republicans could successfully thwart a Democratic wave election, you have to go back to 2011, the Brennan Center experts argue.

That’s the year after Republicans made huge gains in the 2010 midterms, coinciding with the 2010 census where congressional districts were redrawn to reflect population changes.

In a handful of key states, including Pennsylvania, Texas, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Ohio, Republicans went to work redrawing districts. But they weren’t just working off population changes — they were also drawing maps in ways to advantage their party and dilute the voting power of districts with a majority of Democratic voters, a practice known as gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering is nothing new; it’s been happening since the 1800s. But what made the 2011 redistricting so notable is that Republicans had better data to show them where to draw the most effective lines.

“These are the most effective gerrymanders by a long shot,” Li said. “They went to work and they did it; they were aided in many ways by more robust data and more robust technology.”

It’s important to point out that Republicans aren’t the only party that gerrymanders; Maryland is an example of Democratic gerrymandering that has kept Republicans out of power.

Maryland and Wisconsin had their congressional maps challenged, and the cases have gone all the way to the Supreme Court, with the results of the Wisconsin case expected this summer. The outcome of those cases could set a historic legal precedent for the rest of the country, but there’s no guarantee those changes will go into effect before the November midterms.

Li and Royden say the differences are especially pronounced in key states.

“In the battleground states of Michigan and Ohio, for example, even if Democrats match their exceptional performance in 2006 and 2008 — the best Democratic years in two decades in both those states — they are not projected to win a single additional seat under the current maps,” they wrote in their report.

Li and Royden broke down the numbers further in a New York Times op-ed on Monday:

While Wasserman contends that partisan gerrymandering is a problem, he and some other experts don’t think all this can be blamed on extreme gerrymandering. Some of it simply has to do with the trend of more liberal voters moving away from rural areas and into cities — essentially, liberal voters packing themselves into urban districts.

“We’ve seen a phenomenon on the left of Democrats believing this is all a product of Republicans’ bad behavior in the redistricting process, and that’s not the case,” he said.

There are ways to compensate for urbanization trends, as the Pennsylvania Supreme Court showed. They included putting the Democratic-leaning city of Reading into the Democratic county of Chester and spreading blue Pittsburgh into Allegheny County to make it more competitive.

“That fairness doctrine was on display in the Pennsylvania decision,” Wasserman said.

Certain states have been able to make redistricting less partisan

A few states have been able to cut down on partisan gerrymandering, largely because they don’t rely on partisan state legislatures to draw redistricted congressional maps. Instead, they lean on nonpartisan commissions or outside experts to do the job.

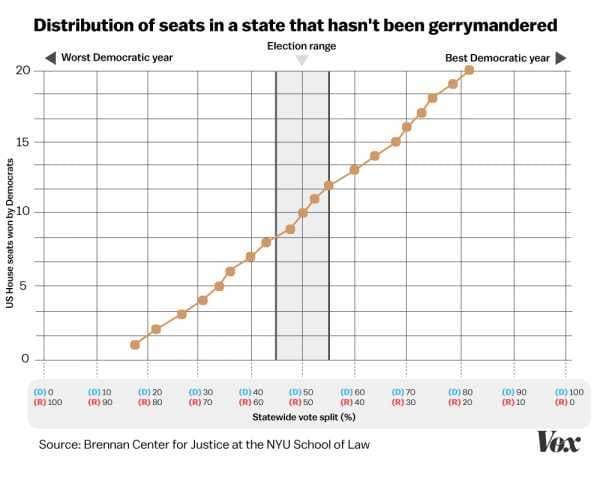

Li singles out states including California and New York as two with congressional maps that are “responsive” to voters; in other words, districts where a party increases its seats as it picks up a larger share of the vote.

For years, California’s map especially protected incumbent politicians of both parties in many “safe” districts until it was redrawn by an independent commission after 2010. A similar situation happened in New York, where an outside expert redrew the map a few years ago.

“New York City is both overwhelmingly Democratic and represents almost half the state’s population. Yet the map is highly responsive to electoral swings,” Li and Royden wrote in their report. “New York Republicans may not have much of a chance to win districts in New York City, but there are plenty of other places on the map where they can, and do, compete.”

In Pennsylvania, the majority-Democratic state Supreme Court redrew the state congressional maps to make them much more competitive. (Pennsylvania Republicans tried to file an appeal to the US Supreme Court, but it was denied.) And with a growing public awareness about gerrymandering, Li is optimistic that more people of both parties know and care about trying to end the practice.

Democrats are certainly sounding the most alarm about gerrymandering leading up to 2018; the Democratic Governors Association just invested $20 million in governors races in Colorado, Florida, Maine, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, states where they want to make sure a Democratic governor is elected, or reelected, in 2018.

States are where the next gerrymandering battle will play out. With the 2020 census the next opportunity to redraw congressional districts, the 2018 elections are a critical time for Democrats to pick up state legislature and gubernatorial seats, where they are badly outnumbered. In 34 states, the governor who will be in office for the next redistricting will be elected in November. So if Democrats want a chance to weigh in on 2021 redistricting, they need to make significant electoral gains this year.

But Republicans also have reason to be worried; if Democrats can sweep 2018 with historic margins, they could have the same thing Republicans have done to them. Republicans like former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger and Ohio Gov. John Kasich have been outspoken about ending the practice, and many voters are paying attention.

“Your average people are concerned with it,” Li said. “There’s a lot of bipartisan support for this. I think it’s an interesting moment.”

Sourse: vox.com