“To Look Without Fear,” which opened on September 12th at the Museum of Modern Art, is the first retrospective of the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans to be held in New York City and his first museum show here since 2006. Born in 1968, in Germany, Tillmans has constructed his art out of a wide-ranging engagement with the world around him and the conditions that have made his life and identity possible. He has photographed friends and lovers; the night clubs in Berlin, where he lives; the Concorde jets that once flew overhead; the materials that give solidity to the structures that surround us; the celestial bodies with which we are in orbit, and the firmament of stars beyond them.

Delayed by a year and a half because of the pandemic, a broad survey of Tillmans’s art was already overdue in New York, not only because of his status as one of the most influential photographers of his generation but also for how the city figures frequently in his images. Some of his earliest art works are photocopied enlargements of the skyscrapers on Sixth Avenue from photos taken on a visit that Tillmans made to New York City as a teen-ager, in the mid-eighties. He returned to New York to live from 1994 to 1996, and, in the past decade, has spent several summers in Fire Island, where he owns a house. His gaze on the city is a knowing one, whether it is turned on a downtown It Girl (a portrait from 1995 of Chloë Sevigny holding an electric guitar), an image of rats creeping around, or the Spectrum, a queer night-life venue formerly located in Bushwick. He also makes music, and the new exhibition includes videos accompanied by the soundtrack of his first full-length album, “Moon in Earthlight.”

“August self portrait,” 2005.

In 2018, I wrote a Profile of Tillmans that familiarized me with his vast body of images. In the dramatic swerves of the years since then, specific works would come to mind as I read and reported the news. Because of his interest in what is new and different in his surroundings, Tillmans tends to notice cycles of change in their early phases. He photographed demonstrators in Union Square after a police officer killed Eric Garner in New York, in 2014, and had works that reflected on the Russian invasion of Crimea that same year and on the suppression of L.G.B.T.Q. identity in Russia. When NASA published the deep-field image of the universe from the James Webb Space Telescope, I was reminded of photographs of telescopic data on computer screens that Tillmans had taken at the European Southern Observatory in Chile, in 2012. Tillmans is H.I.V.-positive and, in his art, he explored medical disinformation, equity, and the pharmaceuticals that keep him alive, long before the debates that overshadowed the scientific feat of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. When I missed going to night clubs in 2020 and 2021, I could look back on his many photographs of clubs and raves, and find an affirmation of partying as a higher-order practice: “I would like to document for the future that it existed,” Tillmans has said, of his night-life photos, “that it cannot be taken for granted, and that there are only a few places in the world where such an intense way of being together so fluidly and freely is possible.”

This might suggest art that is merely topical or journalistic. Instead, what one experiences walking through a Tillmans installation is relief from the usual manipulations of picture-making. His career is a lifelong inquiry into what gives an image meaning, including formalist experiments made without a camera. Amid a cultural outpouring of trolling, bad-faith posturing, disinformation, and edgelord provocation, Tillmans’s sincerity has not wavered, and it will be interesting to see how New York receives it. His evident commitment to the secular liberal consensus might seem wishful, if his freedoms, as a gay man whose life has transcended national boundaries, were not so contingent on politics.

“Faltenwurf (skylight),” 2009.

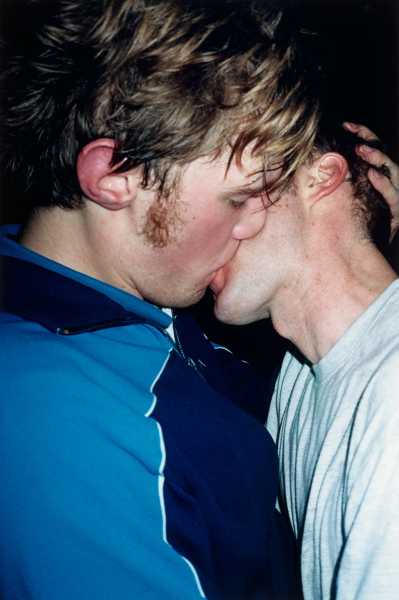

“The Cock (kiss),” 2002.

Tillmans considers his installations as compositions, and part of his artistic practice is personally installing both small gallery shows and major surveys. He often works alone at night in the museums and galleries where his art is shown. His arrangements can be playful, with magazine layouts hung next to printed photographs, all mounted according to a meticulous system that incorporates Scotch tape, binder clips, steel pins, and only the occasional picture frame. In 2005, Tillmans started adding what he calls “Truth Study Centers” to his exhibitions: tables laid out with news articles, images, and ephemera that juxtapose and recontextualize sources of information. At MOMA, the objects displayed on the tables include Swedish postage stamps; an excerpt from the memoir “Close to the Knives,” by the artist David Wojnarowicz; a FedEx envelope bearing the tape and stickers of its journey through U.S. Customs; and an image of the cover of a book called “The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone,” by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett.

An installation view of “Wolfgang Tillmans: To look Without Fear,” on view at the Museum of Modern Art.Photograph by Emile Askey / Courtesy MOMA

I met with Tillmans in the staff café at MOMA in August, during the process of installing the show after a tumultuous spring and summer. In the past calendar year, Tillmans has mounted a gallery show in Los Angeles, a museum show in Vienna, and installations in Accra and Abidjan of “Fragile,” a retrospective that has toured eight African cities. He assisted in making the catalogue for the MOMA exhibition and assembling a new collection of his interviews and writing, “Wolfgang Tillmans: A Reader.” When Russia invaded Ukraine earlier this year, Tillmans experienced the event as an existential threat.

In May, Tillmans took “Fragile” to Lagos. Around two weeks after leaving Nigeria, he learned that a friend and longtime assistant, the Colombian artist Juan Pablo Echeverri, had died, at the age of forty-three, after falling ill with malaria. It is a loss with which Tillmans and his community of collaborators are still coming to terms. I had met Echeverri while he was assisting in the installation of “Fragile” in Nairobi, in 2018; he was warm, irreverent, and very funny. I wanted to be his friend and hoped I would get to meet him again someday. It was not to be. In the show at MOMA, a small portrait of Juan Pablo is set off in a quiet corner.

Tell me what happened with Juan Pablo.

We went to Lagos twice. On the first trip, the art work didn’t arrive. For nine days, we were sitting there, waiting on the crates, which could not leave Ivory Coast for some stupid customs bureaucracy. We had to return after ten days to Berlin, and Juan Pablo had planned to stay two weeks with me, but then we thought, O.K., we want to go back, because we loved it in Lagos. It was such an interesting and special place, and we really thought that this is such a disappointment to not have this crown jewel, like, this city that everybody always talked about, not happen. Then we somehow scrambled our diaries and went back at the end of May and installed the show in a sort of rapid-speed way, and had this wonderful two-day opening.

After that, we all went off to go about our lives. Juan Pablo was preparing for a show in Mexico, then, on a Monday, I think the thirteenth of June, I get the message that he’s in hospital with malaria. He’d gone into hospital on Sunday, and I got a message on Monday. In this scenario, one is still thinking, like, How can this be managed? Can I get advice? Is there something I can do? On Wednesday night, he died of multi-organ failure, and Thursday morning I woke up to the message. When it’s an artist, what stays is the work, and one can sort of focus on that. It’s a grieving practice, almost, to rally around the cause of the work, but I just noticed, when this kicked in a little bit, I thought, like, Fuck, how unsatisfying. Ultimately, I mean, it’s great that we do this, but, you know, you’d rather have the person back.

“Juan Pablo Echeverri,” 2012.

I really felt the news, even though I’d only spent a short amount of time with him.

I mean, it was so fast. Thursday, he felt unwell. Friday, he suddenly had a fever. Everybody says, ‘Yeah, you were in Africa,’ but they just didn’t think of it. And who knows if one would have? I don’t know.

So last night, here at MOMA, you did your nighttime thing?

Every night. Every night, I stay until exactly a quarter to twelve. Then the security guard comes and says, “It’s time.” Because, after midnight, there’s another level of shutdown, and it would have been an even bigger thing to get me in here after midnight. Just working alone on the floor took a long time to negotiate. I am working in the daytime, and people need to be able to ask me things, but then I do need to have this time in the space to actually make the installation, and it can’t be with all these different multitaskings taking place. So it’s not, like, an extravagance. This is how the installations come about—they come about in these two weeks’ time that are this sort of intense immersion in the space and in the building, with team members and then also many hours alone when the team is not there.

What’s it like here at night?

The building is still somehow humming a little bit, like everything in New York is humming. But there is a stark contrast between the public area and the quite, can one say, frugal, offices—sort of sober, utilitarian. And, at night, it’s also kind of curious to walk through areas that are totally filled with people in the day and then are empty. There is something quite special about being in a museum at night. Of course, they didn’t even say that I’m not allowed to walk into other galleries—that went without saying, and I didn’t try my luck. I didn’t want to set off any alarms. I didn’t quickly go to “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.” It’s all dark anyway.

“Tukan,” 2010.

“Lüneburg (self),” 2020.

I wanted to ask about the title of the show, “To Look Without Fear,” and what that means, and what we might be scared of right now.

The title came from an interview where I talked about how I want to encourage myself and others to use our eyes freely, and to not be afraid of looking things in the eye and seeing how reality is in front of our eyes. You don’t have to adhere to a hierarchy that is maybe given in society of what is considered valuable or less valuable, or beautiful or less beautiful.

This is your first retrospective in New York. How does it feel for you to be in New York and showing in New York?

I noticed, while hanging the exhibition, how present New York is in it. It was very inspiring in the mid-nineties, when I first visited and then moved here. And it was super productive, it was a very productive time. And, in a way, when you’re once a New Yorker, I feel like you’re always somehow one. Throughout the past twenty-five years of not living here, I felt a strong bond and connection, also because it’s such a strong art-gallery place, and the visits in the past have also always been visually stimulating, and the scene, and the different evolutions of night-life moments—you know, that photo of the Spectrum that’s in there. And it’s a special audience—I find my New York audience maybe even the best-informed of all cities because there are people I meet that have seen every single show of mine since 1994. I find New Yorkers really go to galleries and really see exhibitions.

Did the fact that the exhibition got delayed change a lot? I mean, it’s, like, a totally different world from the one that it had been planned for—or maybe not. But so many themes you have engaged with for decades in your work seemed to have exploded in the past couple of years.

What I want to avoid is saying that [history] had to come out this way. But, that year, 2014, I visited St. Petersburg three times and very much took this Crimea invasion more seriously than the general public, and then dealt with the censorship there and the issues of gay persecution or the taking away of L.G.B.T. rights. That was a bellwether, you know—L.G.B.T. rights are always a bellwether. And I felt, in the last years, I sometimes felt like, Oh, my God, we’ve made so much progress, and, like, it was assumed that these rights were here to stay. And now we see that the hard right in America is actually willing to take them next, after Roe v. Wade and, of course, in Russia, it’s going backward. And so, having always looked at the world through these particular civil-rights glasses that being gay gave me, I somehow could see the trouble brewing in the world maybe in a more acute way, that it really can affect me, and it will affect me.

With the pandemic, I mean, this is the second pandemic in my life. That was an awareness that people who lived through the AIDS pandemic had: we’ve been here once before, but we’d been here all alone back then—in that eighties period, where people were literally left alone and the President of the United States didn’t mention the word for years after it was discovered and named. These questions of immunity and disease, they’re something that I’ve thought about all my life. I personally didn’t like all this change rhetoric [about the pandemic], only because I think, like, why really does everything have to change? I want to go back and be in a sweaty club, or I want to be able to hug other people, and I didn’t want to ever get into some sort of lust for catastrophe or for permanent change. But one realizes that some things are broken, no? Or haven’t really come back.

Like what? Anything in particular?

I think the fragility of supply chains. The speed of consumption is actually not sustainable, and there are not enough people to deliver the services that hyperconnected metropolitan life requires. I find that unsettling.

There was a little bit of, like, a glitch in the matrix after the pandemic or something, like the thing appeared to be seamless and then wasn’t.

Yes, and somehow, I don’t know. Does it feel like this glitch continues?

It’s got a lot better, but the summer of 2021 was really weird. People had been damaged from the isolation. And then when people gathered again it took a while for it to feel like it was happy. I’m not saying it wasn’t happy, but something hadn’t been addressed. I don’t know how it felt in Berlin.

Yes, the mental damage is larger than I anticipated initially, with people having lost their way or lost hope. And now this super existential threat from Russia is adding to that mindscape. In Berlin, I find it very unsettling that there is this imperialistic force on our doorstep that is not arguing in any reasonable way. The philosophy, if you can call it that, that Putin and his crew have, it’s, like, completely beyond grasp. I feel Western Europe is a small island in a field of diminishing democracy and diminishing freedom. We still have a political discourse of courtesy and reason, which has completely broken in the United States, and to see that this leading country that saved the world in 1945 is coming so close to accepting autocracy is super unsettling. Obviously, I can’t change American politics. I can’t change China or Russia. But what I can do is try and work in the Western European context, where stability and openness somehow are staying, and remind people of the value of those things.

“Wolfgang Tillmans: A Reader” includes a poem you wrote in 2020, in response to the protests after the killing of George Floyd by a police officer. And I was struck by a line about not being able to look back at history.

“Why is it so hard for people to acknowledge the crimes of their forefathers live on today?”

“Black Lives Matter protest, Union Square,” 2014.

It struck me because, you know, Germany had to go through this process with the Holocaust. And, here, it’s like the merest reminder of slavery throws some people into a frenzy. They cannot think about shame. I just wondered if you had any thoughts on that. You really saw it in 2020—this irrational fear that ensues when you state plainly that the American historical record was imperialistic and racist.

When I started spending more time in New York again, in 2014, I happened to be here when the first Black Lives Matter protests happened for Eric Garner. I realized, Oh, my God, this country is, for the first time, actually fully realizing and addressing what happened. I really thought, Oh, there must be something good coming out of this. And somehow, six years later, George Floyd was killed, and it seemed like, actually, nothing had advanced. And that’s not true, because in a large part of the population, things have advanced. It’s just that another large part of the population seems to completely resist this.

In general, I don’t want to rock the boat unnecessarily and I try to have consensus; my ideal society is a consensus society, but I realized that people have to be shocked out of complacency and denial or not even knowing that there was a genocide at the birth of this country. I think it can only be helpful to acknowledge that because you can’t change it, and it certainly isn’t your guilt—you were not responsible for it. But it’s the same with slavery, the way it ended. The fact that there was never talk of reparations is, in today’s light, extraordinary.

And I feel like there’s such a lack of humility, on the part of those who are reacting so aggressively to critical race theory or these trigger words. It’s so unhumble. If you are white and not experiencing daily racism, it should make you feel grateful that you’re not, and humble. You shouldn't further it by aggressively saying, ‘No, it’s not true—it doesn’t exist and we are not a racist society.’ That’s the nature of this particular era now—that, for some, it becomes totally clear that we have to understand gender in a much more complex way, that we have to look at racism in a much more holistic way.

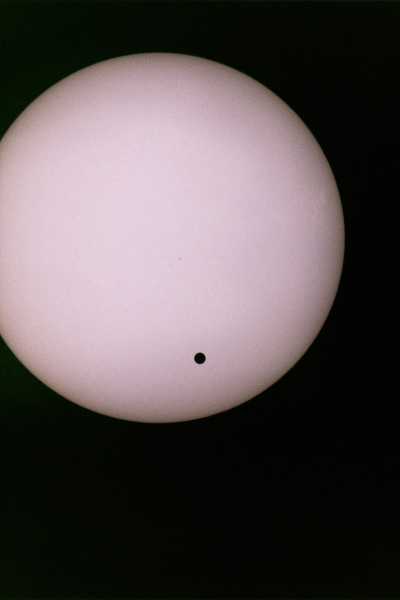

You have had an interest in astronomy since you were a child. You’ve visited NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the European Southern Observatory, and have taken many photographs of the sun, moon, and stars. When you saw the first photos from the James Webb Space Telescope, was it a special moment for you?

Yes, because I learned about it in 2007 in Washington, when I was setting up an exhibition, and I’ve been waiting for this to happen for fifteen years. Really, what I felt was that everybody should see these pictures. They are so humbling that the feeling that I get is, How can anybody want to make life on Earth hell for others when you see just how tiny and meaningless you are in this big picture? I’m, like, You can only be grateful for what you have, and we should all really invest our energy in decreasing suffering. All we can do as humans is make life bearable at worst and pleasurable at best, and negativity is such a waste of time and energy.

“Venus transit,” 2004.

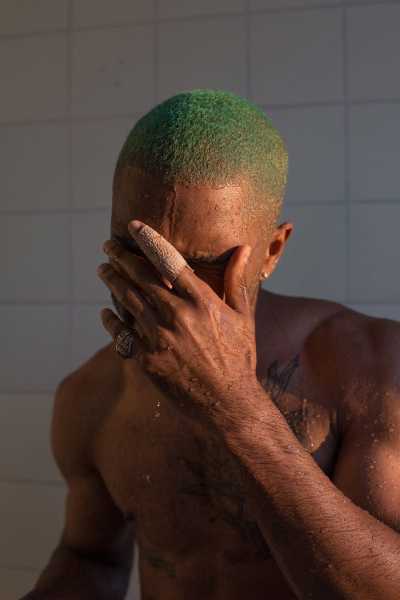

“Frank, in the shower,” 2015.

Well, I felt a sense of relief from a lot of day-to-day political discourse as I walked through the exhibition. It just—it looks like life.

Right? Yes.

But then you realize gathering with your friends can be political. And you realize the night club in Russia or even the ocean pictures take on a different meaning right now. I think, yes, even that stuff becomes political.

I mean, there is something that I feel—for example, this picture called “La Palma,” of the Atlantic Ocean, which captures the details of a foamy wave crashing in almost architectural detail. Or the concrete column [“Concrete Column III,” 2021], of the sort of tiny bits of concrete captured in midair in flight. I see them also as pictures of infinity, of the infinite amount of detail that is hidden in the world that we never, ever notice or see and need to know about, and it’s always too much to ever actually digest and ingest. Maybe I believe that art somehow always brings us close to a, somehow existential, sense of, like, an undertow that connects to all the things we don’t really understand. The thing is to bear what I don’t understand—that’s the labor that I have to do. There is always an underpinning of knowing that you also have to know what you can’t know. And religion is fiction that there is an answer for everything. Or nationalism is an answer for the reality of the complexities of living together on this planet. And so to embrace—to bear—not knowing, can also be very liberating and enlightening.

“La Palma,” 2014.

Is there a new phase right now? Is there a new series or anything that you’ve developed in the past couple of years?

“Moon in Earthlight” is something new that came to completion in the past year and that I feel confident about, because it has developed over many years—it’s not something that I just cobbled together in half a year just before the show. Keeping my eyes interested or staying interested is something I can’t control. The moment I’m not interested, I can also not make interesting pictures. The moment I’m not interested in people, I can’t take a good portrait, so this is a lifelong practice that can never be mastered. I can never master my work in a way that I say, “O.K., I can just continue it in a less engaged way.” It’s either all or nothing. My biggest fear is losing criteria, this inner compass that tells me to do what I do.

You’ve spoken about how when you felt things became over-photographed, then you went into the nonrepresentational for a while.

It’s fascinating that, when I started using photography as my main medium and art, obviously, I had no idea that this medium would become so central to all life, all human life today. It’s crazy, like, people engage and do it every day in a way that was totally unheard of twenty-five years ago. Even though everybody is a photographer now, somehow my pictures still stay recognizable and still stay what they are, which, you know, can’t be taken for granted.

“Freischwimmer 230” (“Free Swimmer 230”), 2012.

“blue self–portrait shadow,” 2020.

If anything, it’s kind of a reminder of what a photo can do.

I find the actual picture-taking process, it’s not, like, a super edifying, satisfying thing. I don’t love being in a night club and taking the pictures, I don’t like to be seen as the photographer that does this, it’s just something that I need to do in order to write this story or tell this picture. The act of photographing is totally counter to being in the here and now because you are engaged in mediation. And so millions and millions and billions of people are constantly mediating the here and now rather than living it. There’s this constant shift of recording and projecting and remembering, and it’s all of course subtracting time of the lived-here-and-now sort, and for that to happen in such gigantic volumes must change society.

Questioning, Why take another picture? has been at the core of the beginning of my work, like, why represent? And what does showing people to other people actually mean? You know, what emotions does it create? Who has the power to represent? The degree that photographs can create unhappiness in lives is not discussed enough. I love photography, but I’m also super critical of its uncritical proliferation. I feel happy that this medium has allowed me to think about the world for thirty-five years. But I also, at the moment, feel like the future might hold something different for me. I want to take a sabbatical. I want to think about what comes next. There is a real urgency that literally everything that I enjoy is under threat with the war in Europe, as one can call it.

You want to just spend some time thinking about that?

I mean, the point of a sabbatical is to not know exactly what direction the research will take. To hold still and slow down, I think, is a good thing for me after the last seven years of incredible developments. To artistically take stock and see what is needed now because “more” has never been reason enough for me—it can’t be the only reason to make things, just to do more.

Since it’s a retrospective, it’s hard to ask a big question that summarizes the whole thing.

I want to encourage people to look without fear, like, to not worry about not getting what the artist says. We have in our own heads our two eyes with the ability to change perspective. I somehow have a very active use of closing one eye and then the other, which is called parallax—seeing the things shift positions in relation to each other and objects of different distance appear in different places from one eye and to the other. And, in this playfulness, in all life’s hardships and challenges, to keep the pleasure of looking, is so important. And it’s free. It’s free of charge. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com