Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

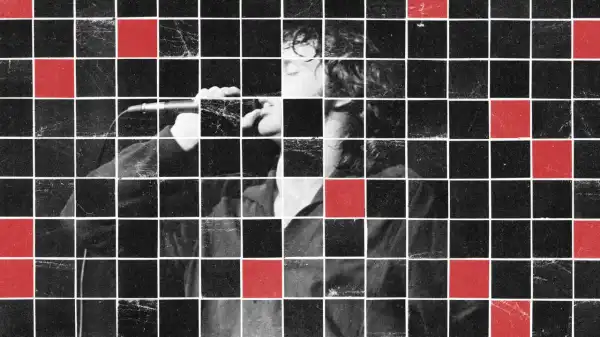

There has always been something about a love of the Doors, especially their frontman Jim Morrison, that has always struck me as undeniably adolescent. The rock band, which existed for just eight years, from 1965 until two years after Morrison’s death at age twenty-seven in 1971, offered a tantalizing proposition to the excited young mind: hauntingly poetic lyrics filled with themes of sex, death, and madness, set to haunting organ melodies and performed by a charismatic singer in black leather who, as the essayist Eve Babitz once noted, was “so attractive that no woman could be safe.” When I started listening to the Doors at fourteen, it seemed both urgent and erotic, as if I were entering a new and dangerous world of adulthood. The music inspired wonder and nostalgia. In other words – and I swear I don’t mean this in an offensive way – it was music for the innocent, just discovering sex.

In the documentary miniseries Before the End: Searching for Jim Morrison, now streaming on Apple TV+, director Jeff Finn recalls hearing the Doors as a child and thinking of their eerie sounds as “Halloween music.” But he dates his true love for the band and its singer to his teenage years. “I was hooked,” he says. The band’s music and visuals resonated with him, as did the story of Morrison’s short, turbulent life and, in particular, his mysterious death. In the spring of 1971, the singer took a break from the Doors to focus on his poetry, which he published under his full name, the more discreet James Douglas Morrison, and moved to Paris with his girlfriend Pamela Courson. Just four months later, in the early morning of July 3, Courson discovered his body in the bathtub of their Marais apartment, and he was buried shortly thereafter in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Morrison’s death certificate states that his heart stopped, but Finn has questions. Why was there no autopsy? Who was “Dr. Max Wassill,” the man who signed the certificate, and why was he never found after the fact? Why was Morrison’s coffin sealed? Why was his American passport never found? What about the singer’s alleged desire, as more than one acquaintance has suggested, to fake his own death and escape the burden of rock stardom? The story of Morrison’s death, Finn fascinatingly tells us, is “an unsolved case” that “raises questions about the existence of a conspiracy.”

Finn is probably not the first to question the official version of Morrison’s death. In his memoir, Wonderland Avenue, Doors collaborator Danny Sugarman (also the co-author of the 1980 best-selling Morrison memoir, No One Here Gets Out Alive) recounts how fans continued to spot the singer in places as remote as the Congo and the Australian outback, long after his death. (“Morrison, meanwhile, refuses to die,” Sugarman writes.) Finn’s stated goal in Before the End is to finally sort out these speculations and find out what really happened to Morrison. “I’ve dedicated my life to finding the truth about events that happened fifty years ago,” he says. He mentions that “since I was 18, [I’ve] been looking for Jim Morrison, literally and figuratively.”

The main problem with Before the End, however, is that Finn allows the figurative aspects of his search to overshadow the literal, and viewers hoping for some facts about Morrison’s whereabouts after 1971 will likely be disappointed. Finn says that in his years-long investigation into the singer’s life and death, he interviewed hundreds of people connected to Morrison—childhood friends, family members, old lovers—and crisscrossed the country several times in search of clues and answers. Still, the series is less a document of a thorough investigation than a twisted chronicle of a teenage quest for revelation and salvation.

Finn’s voiceover may be the first clue that Before the End won’t be solving the case in the traditional detective sense. “Join me as I go down the Morrison rabbit hole, but I can’t guarantee you’ll come out all right,” he says early in the series, as if he’s about to show you how Pink Floyd’s “The Dark Side of the Moon” fits perfectly with “The Wizard of Oz.” (In general, Finn has a penchant for hyperbole: the details he shares with the viewer often “stun” or “shock” them; after hearing a certain unexpected piece of information from a source, he says his “jaw had to be lifted off the floor.”) This melodramatic streak is also evident in the documentary’s visual language, which consists of shaky interviews with sources, random street shots, and seemingly gratuitous archival footage, occasionally overlaid with what look like iMovie effects and graphics. Despite the series’ rather unexpected offering on Tim Cook’s streaming service, it’s peppered with the stylish jargon of conspiracy rock

Sourse: newyorker.com