Every photographer has a give-and-take relationship with her subjects. Wendy Ewald has more give than most. Since 1975, the American artist has been entwining photography, activism, and education in a series of collaborations that upend our prevailing ideas of authorship and authority. For months, even years, at a time, she has moved into rural communities around the world—from Mexico and Morocco to India and the Netherlands—to teach local children how to use cameras. The resulting black-and-white photographs are credited to both Ewald and her students, who are quoted and named in the titles. (This started twenty years before the term “socially engaged art” entered the lexicon.)

The pictures can be funny but they are also frank. What they are not is sentimental. Encouraged by Ewald to delve into their dreams, the children return from sleep with visions as dark as as a Grimms’ fairy tale: of killing a best friend, or of a brother buried under a woodpile. But it’s the revelations of waking thoughts that truly disturb. A white girl in South Africa describes her photograph of a black man on the sidewalk, from 1992, with the words “What I Don’t Like About Where I Live.” In its exposure of casual racism, among other harsh realities, Ewald’s project sidesteps what Teju Cole has described as “the white-savior industrial complex” that plagues, for example, the feel-good documentary “Born Into Brothels.”

“My lame cousin-brother is dressed like saint Sadhu Hari,” Kalu Rupsingh, India, 1989-90.

“I Am the Girl with the Snake Around Her Neck,” an indelible self-portrait taken in Appalachian Kentucky, in 1980, by a girl named Denise Dixon—seen in the close quarters of a wood-panelled room wearing a dishevelled blonde wig, a pout, and a garter-snake boa—evokes a pint-size Cindy Sherman. (In fact, the image has been on view at the Whitney Museum, in the 1997 Biennial.) “A White Swan in the Middle of the Polder,” shot by Miranda Plooij, in the Netherlands, in 1996, is every bit as uncanny as the swan in Diane Arbus’s “Castle at Disneyland.” Here, the white bird floats not in a moat but on a dark sea of grass, bisected from clouds by a crenulated horizon of trees.

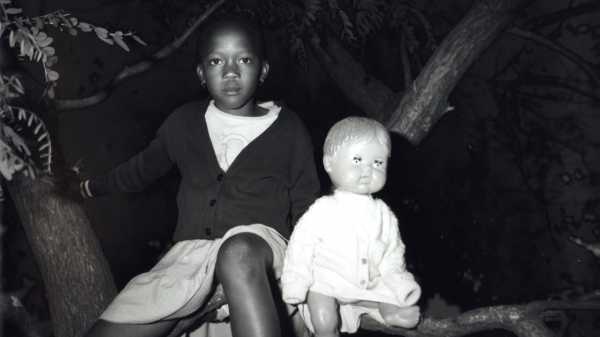

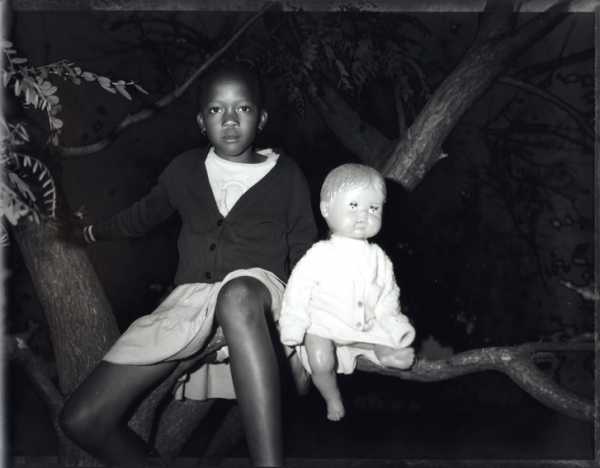

“A Dream of Shata and the doll,” Franklin Monnakqtla, South Africa, 1992.

Ewald began taking photographs when she was a child herself, growing up in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. She received her first camera from her mother, at the age of eleven. The seeds for her collaborative future were planted in the summer of 1969, after her high-school graduation, when she travelled to the Labrador, Canada, to help set up a day camp for Innu and Mi'kmaq children, born into semi-nomadic families but now living on a reservation in its first year. Ewald arrived with Polaroid Instamatics for the children and a large-format camera for herself. Her dreams of becoming a civil-rights-era Dorothea Lange were complicated by her realization that the children (some nearly her age) were taking “more powerful and more intimate pictures than I could,” as she later said.

“I am the girl with the snake around her neck,” Denise Dixon, Kentucky, 1980.

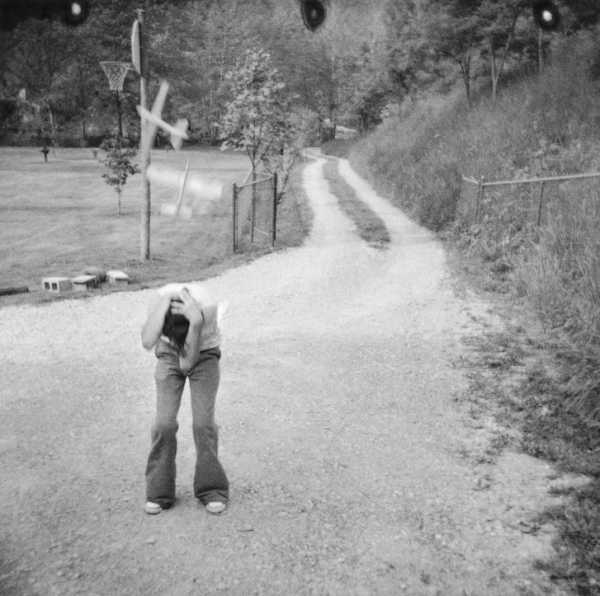

“The planes were crashing on my head,” Scott Huff, Kentucky, 1978.

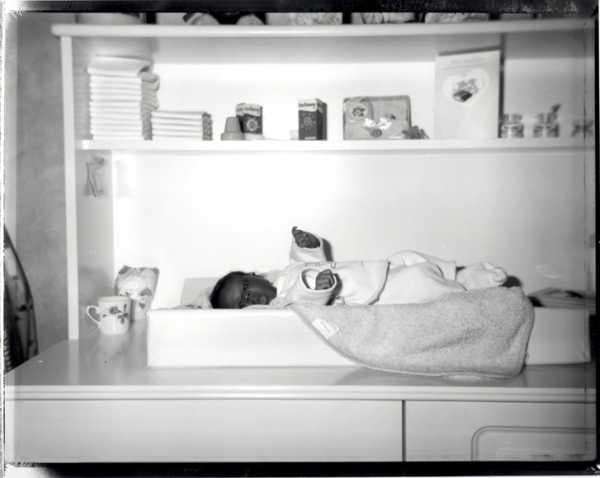

“This is my new cousin, his name is Patrick,” Lucy Dias Semedo, The Netherlands, 1996.

In college, Ewald pursued photography as an artist rather than as a documentarian, studying for two years with the American modernist Minor White, at M.I.T. In 1975, she moved to Whitesburg, Kentucky, to take her own pictures, while teaching workshops—including a stint in the last one-room schoolhouse on Kingdom Come Creek—under the aegis of Appalshop, a film-arts center named for Appalachia, founded in 1969. (It’s still going strong.) Ewald lived in Kentucky for six years and it was there that she arrived at her compassionate strain of conceptualism. As she wrote in the monograph that accompanied her museum retrospective, “Sometimes I think I disguise myself as a teacher in order to make the pictures that I need to see.”

“The sleepyhead,” Luis Arturo González, Colombia, 1982-1985.

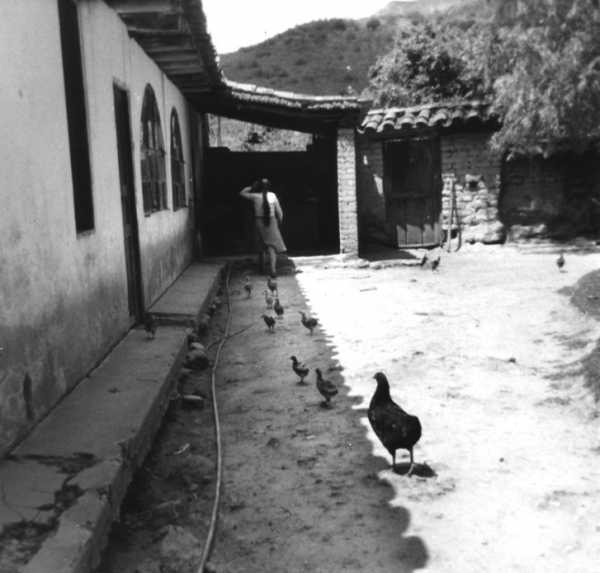

“The chickens run behind my mother,” Carlos Andrés Villaneuva, Colombia, 1982-85.

“Here is my cousin, Miry, with the skulls and fruit for the Day of the Dead,” Juan Jesús Murillo, Mexico, 1991.

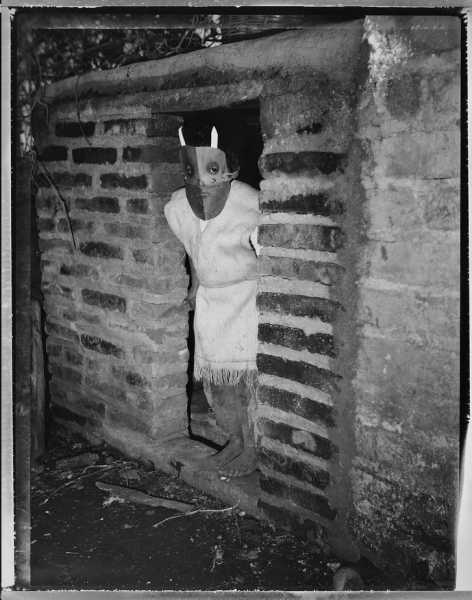

“The devil is leaving his cave,” Reymundo Gómez Hernández, Mexico, 1991.

“My little sister is praying,” Mounia Betioui, Morocco, 1995.

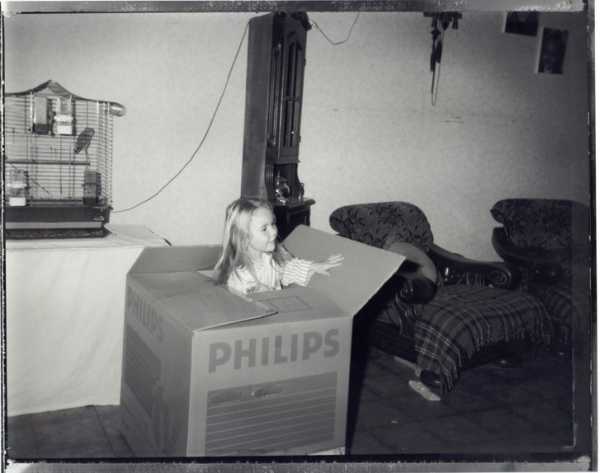

“Surprise!,” Suraya Beije, The Netherlands, 1996.

“The thief caught in the living room,” Fatima el Farroudi, The Netherlands, 1996.

“Saint Bhaataji cut off my hand,” Dasrath, India, 1989-90.

“A white swan in the middle of the polder,” Miranda Plooij, The Netherlands, 1996.

“Wendy Ewald: Works, Projects, Collaborations 1975-1996” is on view at the Steven Kasher gallery through June 2nd.

Sourse: newyorker.com