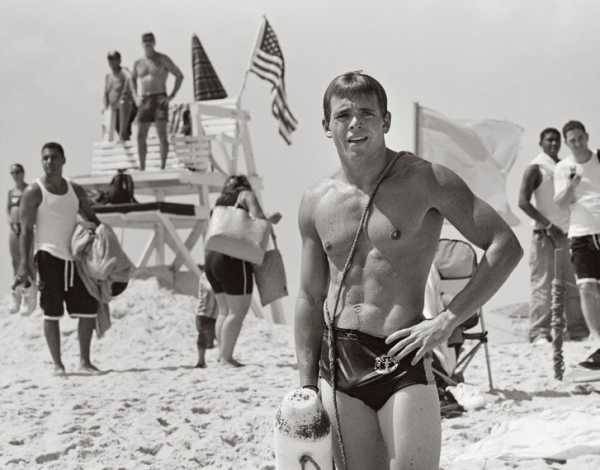

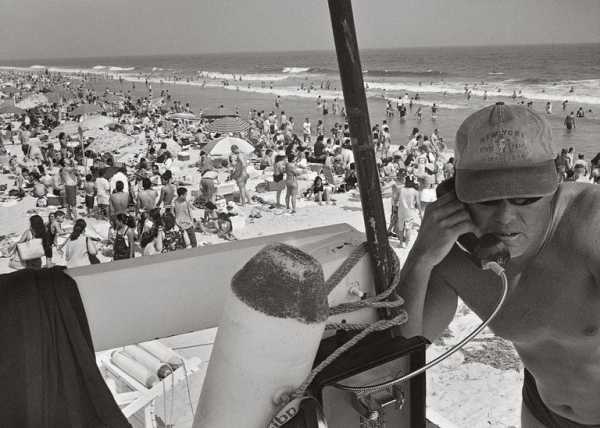

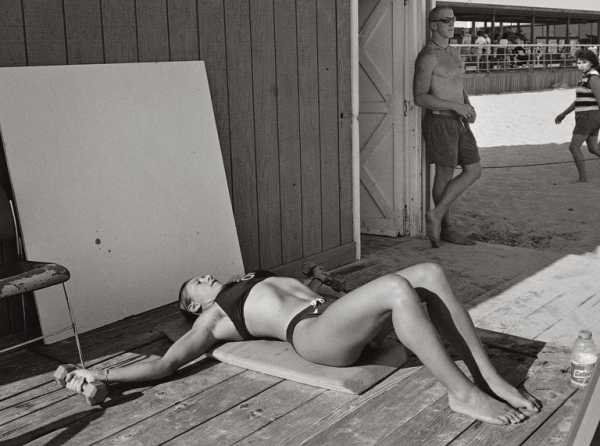

“The hard-core lifeguards return decade after decade, like the swallows to Capistrano,” Greg Donaldson, who worked as a lifeguard at New York’s Jones Beach for twenty years, wrote once, in an essay for New York. The same is true of the photographer Joseph Szabo. An avid chronicler of American youth, Szabo began taking pictures at Jones Beach in 1960, and returned year after year to capture the diverse human menagerie that gathers every summer: the evolving styles of swimsuits, the near-naked bodies in their limitless variety, the jubilance and intimacy of a day at the beach. Floating above it all, in Szabo’s scenes, is the figure of the lifeguard, on a high perch, upright and vigilant amid the languid bodies and umbrellas below. Sometimes they are a taken-for-granted part of the landscape, their chairs blending into a wide-angle view of the crowd; sometimes they’re godlike, on a literal pedestal and shot from the ground.

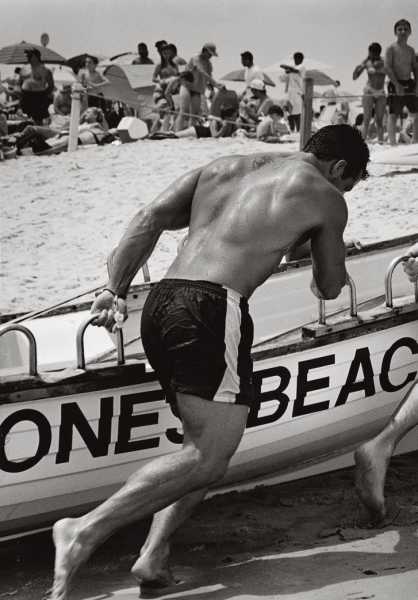

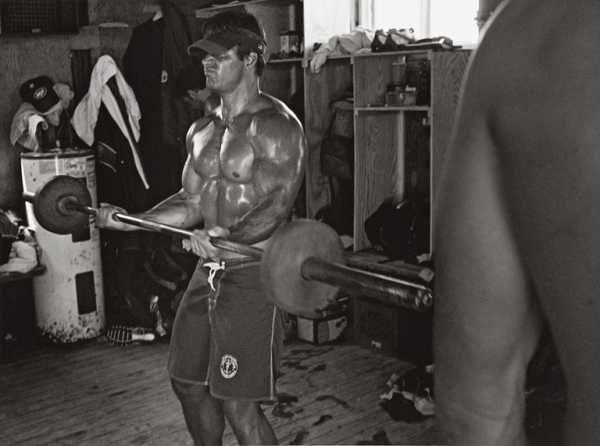

Lifeguarding at Jones Beach is not like lifeguarding at the local pool. The beach occupies a six-and-a-half-mile stretch of the coast on Long Island; according to the Parks Department, it hosts six million visitors a year, and on hot days beachgoers pack the sand shoulder to shoulder. In his “Lifeguard” series, which is collected in a new volume from Damiani, Szabo captures the strenuous physicality of the lifeguards’ work—the muscles glistening under sun-baked skin, the workouts to maintain such fitness. But he also captures the sensation of endless summer days and, somehow, of endless youth. The images in Szabo’s book span the past three decades, but they have a timeless quality. It’s hard to place toned bodies and sea-tousled hair in any particular decade.

Checking the safety of beach visitors, 1993.

Pushing the lifeguard boat up the berm, 2007.

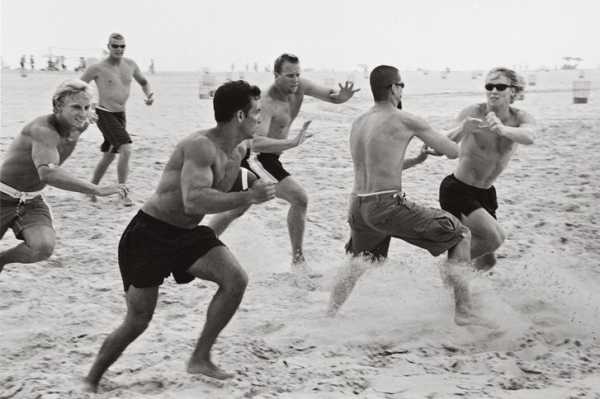

Lifeguards occupy a peculiar cultural niche, at the intersection of “Baywatch” and beach bum, of battle-hardened hero and teen-age wastrel. Those who work on busy beaches, such as Jones Beach, often have backgrounds as élite competitive swimmers, yet much of their job entails sitting, and tanning, and watching and watching and watching. “Unlike guards at most California and East Coast beaches, who almost always sit alone, Jones Beach veterans recline on elaborate tiered main stands that accommodate seven or eight guards at once,” Donaldson wrote. “While the newcomers and weekenders ride the wing stands solo, the full-timers with seniority sit together, study the water, and kibitz. When they're on the clock, they alternate an hour on the stand with an hour off to exercise or surf.”

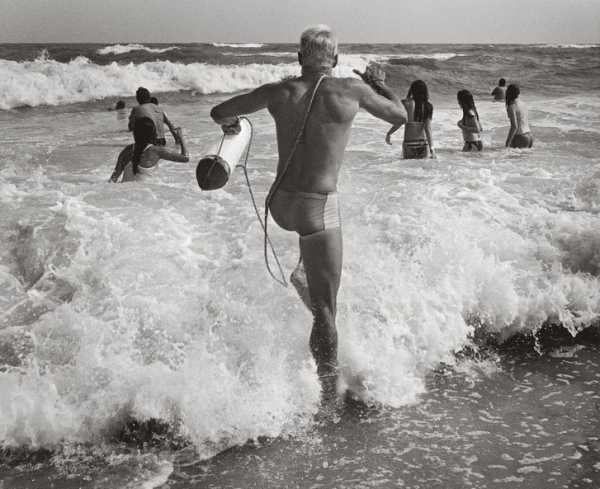

But then there are moments of action, sudden and high-stakes. Szabo’s photographs of rescues are continually surprising—when the funny-looking flotation devices and the golden limbs have snapped into action and entered the waves, rushing into the froth while everyone else just stands and stares. It suddenly seems like an absurd and dangerous thing to throw oneself into the ocean for fun.

Launching the Jones Beach lifeguard boat in heavy surf, 2007.

Touch football on a cold day with no beachgoers, 2001.

The beach is packed on a hot, humid day, 2007.

Watching out for swimmers in need, 2002.

Guards from Jones Beach’s Central Mall watch a potential rescue, 2000.

On alert after several exhausting saves, 2006.

Lifeguards charge the surf for a rescue, 2007.

A lifeguard on the job, 1994.

Answering the telephone at the main lifeguard stand, 2000.

A lifeguard helps reunite a girl with her mother after the girl got lost on the beach, 2013.

Fitness training, 2007.

Training at the lifeguard shack, 1996.

Meeting about the day’s work, 2015.

A lifeguard makes a rescue, 2007.

Sourse: newyorker.com