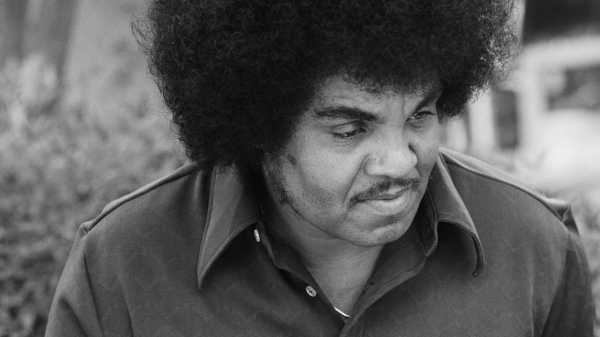

Joe Jackson, the troubled patriarch of an American musical dynasty, died on Wednesday, in Las Vegas, at the age of eighty-nine. An official cause of death has not been announced, and probably won’t be; in a recent interview, Jermaine, one of his sons, said that Jackson had been ill for a while and was refusing visits from most members of his immediate family. If that sounds uncommonly cruel, it’s in keeping with Jackson’s reputation as a figure who was vituperative and hysterically unforgiving, particularly toward his eleven children—an “ungodly, God-like man,” to borrow a phrase from “Moby-Dick.” Michael, his eighth child, once told Oprah Winfrey that he was so afraid of his father that he sometimes threw up when he caught sight of him. In 2010, Jackson admitted to whipping his kids with straps and belts. “I just remember hearing my mother scream, ‘Joe, you’re gonna kill him, you’re gonna kill him, stop it,’ ” Michael told the journalist Martin Bashir, in a 2003 television interview. He added, “I was so fast he couldn’t catch me half the time, but, when he would catch me, oh my God, it was bad. It was really bad.”

Joe Jackson was born in Fountain View, Arkansas, in 1928. After his parents divorced, he moved with his father to Oakland, California, while his mother and siblings settled in East Chicago, Indiana. Jackson joined them there when he turned eighteen. He got a job at the Inland Steel Company, and began training as a boxer. In 1949, after he and his first wife divorced, he married Katherine Scruse, and the following year they bought a modest two-bedroom house in Gary, resettling in a steel town, just in time to watch the steel industry expand and then collapse on itself.

In 1964, Jackson corralled three of his eldest sons—Jackie, Tito, and Jermaine—into a musical group. (Marlon and Michael joined later.) The Jackson Five appeared on the Chitlin’ Circuit (a collection of clubs in the South, Midwest, and Northeast where African-American acts could perform freely), and, in 1967, the group won a talent competition at the storied Apollo Theatre, in Harlem. An audition tape was mailed off to Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown, who initially passed on the band—he has given the excuse that he was distracted by Stevie Wonder, then a recent Motown recruit—but eventually signed the act, in March of 1969.

The tape that Jackson sent to Gordy is on YouTube, for anyone who wants to witness a tiny bit of genius unfolding in the corner of a dim room. The band does a groovy version of “I Got the Feelin’,” which had already been a sizable hit for James Brown, in 1968. Michael, who was then just ten years old, sings lead. Later in his career, his performance style was often compared to Brown’s, and you can see it developing here, in the easy, stirring way he moves—it’s as if the music infected him and took hold of his limbs, like some wild virus. At one point, he does a full spin, and then something that appears to be a proto-moonwalk, or at least a sublime imitation of the foot scoot that Brown often did from one side of a stage to the other. The image quality is awful, of course, but it’s impossible not to feel like something preternaturally great is unfolding. Was it Joe Jackson holding the camera?

By January of 1970, the Jackson Five’s “I Want You Back”—which, nearly fifty years later, remains one of the best American pop singles of all time—was at the top of the Billboard Hot 100. In 1971, the Jacksons performed the song on a television special called “Goin’ Back to Indiana.” That, too, is now on YouTube. Michael was twelve by then, and missing a tooth; in the clip, he wears a desert-themed jumpsuit, with cacti on his pant legs. How uncanny that a child can sing a line like “Oh darlin’, I was blind to let you go” and have it sound so convincing, so full of yearning and ardor! By 1971, Michael, under Joe’s tutelage, would launch a solo career, but not before the Jackson Five had four consecutive No. 1 hits. Joe insisted on the band’s success, which, I suppose, was his success. The rehearsals were famously gruelling.

When Janet, his youngest child with Katherine, turned sixteen, Jackson negotiated a recording contract for her, with A&M Records; under his supervision, she made two cloying and mostly unremarkable pop albums. It wasn’t until Janet severed professional ties with her family, in 1986, that she arrived at something singular, a kind of actualization. “Control” is technically her third record, but it feels, in almost every way, like a début. On her own, Janet was fierce, empowered: “No, my first name ain’t baby,” she announced in “Nasty.” “It’s Janet . . . Ms. Jackson if you’re nasty.”

What to make of this inscrutable man, whose children made such beautiful records? There are often good questions to ask of the people adjacent to prodigies—the producers, managers, partners, assistants, and so on, whose efforts are silently folded into the work, bolstering if not enabling it, becoming a part of its story. When a father gets this involved in his kids’ careers, one hopes that it’s merely to protect his offspring from mercenary or manipulative forces, from rocketing into adulthood, from being exploited in some unforgivable way. Jackson’s actions toward his kids were, by many accounts and measures, evil. It is difficult to square his presence in his family’s life with the glorious, life-affirming songs that his kids made. In the end, let’s cling to those.

Sourse: newyorker.com