In his youth, Richard Garfield, the mathematician who created Magic: The Gathering, liked to play and invent games. Before his family settled in Oregon, in the mid-seventies, he spent many of his early years in Bangladesh and Nepal, places where his father worked as an architect. Garfield didn’t speak Bengali or Nepali, so, to make friends, he would unpack a deck of cards or spill out a bag of marbles. Back in the United States, around the age of thirteen, he began to hear about a game called Dungeons & Dragons—he was told that it had pit traps and orcs and treasure—but his local game store didn’t have the rulebooks yet, and none of his classmates knew how to play. A lack of language had never stopped him before; he made something up.

The game he devised was nothing like D. & D. “It was more like a Clue board,” he recalled. “You could move around the map and go into different rooms and then there would be monsters in these rooms.” You could also “win” in Garfield’s version. When the zine-like D. & D. manuals finally arrived, he was astonished to discover that you could keep playing the game indefinitely. Players would collectively tell a story about their characters wielding enchanted swords or picking locks, with dice rolls deciding many of the consequences. “It puts players in the position of game designers,” Garfield told me. The books themselves “were dreadfully written,” he said. “The game was very hard to learn from the rules, which is something it shares with Magic, I guess, but its brilliance shone through.”

Like the misfit musicians who bought the Velvet Underground’s first album, the young kids of the seventies who pored over the first set of D. & D. manuals all went out to make their own games. The ideas that bubbled up in the following decade flowed in a similar direction. Wiz-War had wizards hurling fireballs at each other in a maze. Titan had players commanding an army of mythological creatures like centaurs and griffons to attack the other players’ titans. Garfield himself made a game called Five Magics. He granted elemental characteristics to five distinct colors of energy that arose, as in many other fantasy games of the period, from different geographies. The colors shifted around, but, eventually, red aggression came from mountains, black ambition from swamps, blue rumination from islands, white orderliness from plains, and green growth from forests. Garfield never considered Five Magics publishable and, because of constant tinkering, he never played it the same way twice. Sometimes it was a board game. Sometimes it was a card game. “There were some versions where you collected victory points to win,” he recalled, “and some versions where you wiped out your opponents.”

It wasn’t until 1991, when a friend put him in touch with a gaming entrepreneur named Peter Adkison, that Garfield, by then finishing a Ph.D. in combinatorial mathematics at Penn, thought he could make something of his creation. Adkison lived in Seattle and worked a day job as a systems analyst for Boeing; he moonlit as the founder and C.E.O. of a gaming company called Wizards of the Coast. He met up with Garfield in Oregon, where the young mathematician was visiting his parents. The lives of these two men and what followed has been chronicled, especially in books like “Jonny Magic & The Card Shark Kids" by David Kushner and “Generation Decks” by Titus Chalk, with particular attention to what happened at this fortuitous moment: Adkison suggested that Garfield create something portable that people could pull out during their downtime at the conventions where nerds flocked to find rare comic books, purchase esoteric collectibles, and discover new games.

After the meeting, Garfield drove outside Portland with his family and hiked a path that winds to the top of Multnomah Falls. As he circled his way up, he had a burst of inspiration. People playing a game like Five Magics could separately collect different cards, have different decks, and come up with different strategies from those decks. In doing so, they could transcend the game itself and express, in the midst of calculations concerning goblins and demons and angels, something that would be unique to them: an identity. “Magic is closer to roleplaying than any other card or board game I know of,” Garfield later wrote. “Each player’s deck is like a character.”

He met Adkison again near the Wizards office, and, when Adkison heard the idea, he started yelling and hollering with excitement. He instantly grasped that the game that would become Magic wasn’t like Monopoly or Clue, which families purchase once and use for a lifetime. Players would want to acquire more and more cards in order to remake the game and find their own unique expressions within it. “If executed properly,” Adkison wrote in a post on Usenet, the cards “would make us millions.”

Magic: The Gathering débuted in August of 1993, and had a modest initial print run of 2.6 million cards with fantasy illustrations to match. Over the next decade, it would inspire a genre of collectible-card games such as Yu-Gi-Oh! and Pokémon. Mel Li, a game designer who has a Ph.D. in biomedical engineering and who worked at Wizards until last year, discovered the game in 1995. “I grew up in the suburbs,” she said. “You spend a lot of time on your own.” Magic gave her nerdy friends something to talk about in the schoolyard, a “common language.” The next year, Mirage, a set of Magic cards with African fantasy elements, came out. “That was eye-opening for me,” she told me. “It wasn’t a typical, Tolkien-esque vision of what a fantasy world should be.” Her mom and dad thought it was a waste of time, so she kept her cards hidden in a shoebox under her bed. “I’d lay them out and make decks at night,” she recalled, “when my parents were asleep.”

In the game, players were fashioned as “planeswalkers,” who cast spells and travel between planes of existence. The spells themselves were the cards, which could be purchased in places like bookstores and comic-book shops. It soon became a common sight to see kids ripping off the wrappers of Magic packs, and—as a blend of chemicals from the bouquet of ink and finish wafted up—taking account of what they possessed of the two hundred and ninety-five cards that Garfield and his colleagues had conceived. The cards had names like “Bad Moon” and “Celestial Prison” and featured beasts such as “Giant Spider” and “Gray Ogre.” Garfield devised a set of rules about how many cards to draw each turn, how to charge up magical powers, or “mana,” from so-called land cards, and how to cast spell cards and summon creatures to bring an opponent’s life total from twenty points to zero. Flowing through this was a strain of wild invention: the cards often gave players the license to bend or change the rules.

To change more rules, you needed to buy more cards. Many of the most powerful cards were rarely printed, which drove fans to crack open even more packs. By November of 1993, under the headline “Professor’s Game Casts Magic Spell on Players,” the Seattle Times reported that ten million cards had been sold in a few months. “I’ve wasted—no not wasted—I’ve used all my money just buying Magic cards,” an eleven-year-old boy named Jake told the Washington Post. He carried his deck around with him everywhere he went in case a game broke out. By 1997, Magic: The Gathering was so successful that Wizards of the Coast acquired Dungeons & Dragons. Newsweek noted that Wizards had sold two billion cards. A game like Magic, Garfield told the reporter, could “take over your personal operating system, like a virus.”

Since its beginning, Magic has spread to more than thirty million human operating systems. Today, those humans play with some combination of the game’s eighteen thousand unique cards, in eleven different languages. Magic YouTube shows like Geek & Sundry’s “Spellslingers” regularly draw hundreds of thousands of views. In a video on a channel called “openboosters,” a man opens a very old pack of cards and his gloved hands begin to tremble when he finds a “Black Lotus,” the most coveted card in the game. That video has six million views. Last year, I spoke to a game-store owner named Jon Freeman about the cultural resurgence of Dungeons & Dragons, a fantasy mainstay with a much higher profile than Magic’s, and he told me that, in his store, “if you want to look at the sheer number of people who are playing games, Magic far exceeds all of the above.”

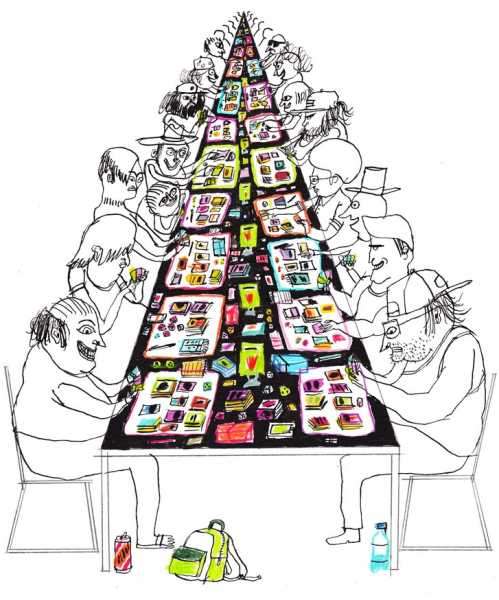

Even as it has grown in popularity and size, Magic flies low to the ground. It thrives on the people who gather at lunch tables, in apartments, or in one of the six thousand stores worldwide that Wizards has licensed to put on weekly tournaments dubbed Friday Night Magic. Freeman’s shop, in Brooklyn, does three or four a week. For especially dedicated players, Channel Fireball, a Magic event organizer that takes its name from a devastating two-card attack, puts on some sixty “Grand Prix” tournaments every year in countries across the planet, from Japan and Poland to Australia and Brazil. Recently, Magic had gathered some of its most notable fans in Las Vegas to celebrate its twenty-fifth anniversary. Channel Fireball was also holding its largest tournament of the year, with six thousand people in attendance. One player called it “Magicpalooza.”

The people who make up gaming communities were once seen as sun-shunning nerds who were pushed to one side by the rest of society. Now, with the spread of the Internet, their world is everyone’s world. The culture of fantasy and gameplay informs movies, television, and memes, and has become a lingua franca of communicating online. Lately, there seems to be more at stake in these virtual conversations, and a sense of rejection can come from any direction. Even before the success of Magic, Wizards broached problems of inclusion and civility in the gaming community. It was Seattle in the nineties, Adkison told me, and such progressive ideas were in the air. In our culturally embattled present, Magic has found millions of new fans, but the same unrealized hopes for a diverse, plural, welcoming community persist. The long-running efforts in Magic reflect our struggles everywhere.

The world of Magic can seem arcane from the outside. Players mutter about “netdecking,” “mana flooding,” and “karoos.” “I got rid of two ‘Skin-Witches,’ ” one young white man in shorts said to another young white man in shorts as I passed them on my way to the Las Vegas Convention Center. Once inside, I watched a woman with green hair posting blue sheets of paper on either side of a tall blackboard. A crowd of men and a few women rushed in to find out where they would sit to compete for a chunk of a fifty-thousand-dollar pot and for the chance to play on the Pro Tour, a higher-echelon series of tournaments with bigger cash prizes.

Beyond them, I saw people perusing vender stalls selling rare and desirable cards laid out in rows on tables or in glass cases. Some of them, called “foils,” have a glossy sheen. A coveted “Black Lotus” sat under glass in a plastic sleeve. The sticker price: sixteen thousand dollars. At another booth, hopeful customers were spending hundreds of dollars on old packs and then opening them on camera to see what they got. Many cards are deemed “worthless,” either because they have no market value or, not unrelatedly, because no one has found a significant use for them in a tournament-approved deck.

“Magic is a big tent,” Chris Cocks, the newly minted C.E.O. of Wizards of the Coast, told me before I left New York for Nevada. The Grand Prix in Vegas, he said, “is one of our biggest forums to see just how wide and vibrant that tent is.” Among the rows and rows of tables, there were sparks of diversity here and there. In the middle of one line of mostly white men, I spotted a woman with dreadlocks who was painted purple and kept a severed head next to her while she played. At the end of another table, two auburn-haired men squared off against two older women with glasses, one of them using her walker to hold a box of unopened cards.

After an hour of wandering the hall, I found the competitive Magic player David Williams wearing a Las Vegas Golden Knights cap and leaning back in a chair at one of the long tables full of people engaged in small-prize games. A number of Magic fans I spoke to told me that top-level players like Williams, Jon Finkel, Melissa DeTora, and Reid Duke, known as the Gentleman of Magic, brought them into the game in the way that middle schoolers join Little League to be like the Astros’ José Altuve or Mookie Betts of the Red Sox. But several top-tier aspirants complained that, unlike athletes with Major League salaries, they can’t just depend on their winnings to get by. Williams, like many accomplished Magic players, has made most of his money in professional poker. He was also on a recent season of “MasterChef,” in which Gordon Ramsay came into his kitchen and told him not to doubt himself.

It seems Williams has rarely had reason to. Despite first learning how to cook a few years ago from what he called “the school of YouTube,” he became a finalist on Ramsay’s show. His time in Magic goes back to 1994, he told me, after he came across a few packs sitting by the register of a video-game store. One of his few brief withdrawals from intensive Magic came in 2004, when second place at the World Series of Poker earned him three and a half million dollars. Another was when he was discovered, perhaps unintentionally, to be playing with marked cards at a Magic World Championships tournament, in 2001.Williams discovered competitive poker at a Magic tournament, but Magic, to his mind, is the superlative game. And Wizards loves having him as a kind of ambassador: “Thank you @wizards_magic,” he later wrote, in a sponsored tweet, “for having me help celebrate Magic’s 25th anniversary!”

When we spoke, he lauded the game’s inclusive spirit, but he was also frank. “People of color are not as represented here,” Williams, who is half Persian, half African-American, told me. “But there’s no reason for it. In all my years of going to Magic events, I’ve never had one instance of even close to discrimination or anybody being racist. Nothing. Ever.” Several players told me that smaller tournaments offer more unseemly behavior, though event organizers have started to address these concerns. One such player, from Connecticut, praised Wizards’ zero-tolerance policy toward bigotry of any kind, enforced by the judges who stroll between the tables in black button-downs and whose main job is to clarify ambiguities that come up in the play. “I have had an opponent disqualified at an event for making a racist statement—not to me, just out loud,” he said. “The player sitting to my right reported them to a judge. I confirmed his statement and, midgame, the player was told to leave. They were upset with themselves more than anyone else. The rules are very clear.”

A couple of hours later, at the birthday dinner Magic threw for its twenty-fifth anniversary, Josh Lee Kwai, a Magic YouTube personality, introduced me to the N.F.L. defensive end Cassius Marsh, a frequent guest of Lee Kwai’s popular video series “Game Knights.” Lee Kwai wanted to show me that Magic players come in all shapes and sizes. Marsh, who plays for the San Francisco 49ers, comes in the shape of a two-hundred-and-forty-five-pound man with curly blond hair. He has a web of tattoos that runs over and across his muscular arms and shoulders, like the armor of a Byzantine soldier. We sat down to talk by a long poster of a planeswalker named Liliana casting a spell over a legion of zombies.

“When I was younger, I would ride my bike to the card store almost every day and see if anyone was in there to play, and if not, I would just sit and mess with my cards,” Marsh told me. “I didn’t tell too many people about it. It was my little secret. I had my friends from the card shop, but that was pretty much it.” As a high-school athlete, he didn’t think his football friends would understand, but his adult teammates at Levi’s Stadium have recently approached him, curious about the game. “I’m trying to teach Joe Staley and George Kittle right now. I gifted them a box of Amonkhet,” he said, referring to a Magic set with art inspired by a sinister version of ancient Egypt, “and one of them opened up a really good card.” He laughed. “I was pretty pissed about it.”

Marsh is a beloved member of the Magic community, and a prominent example of the contemporary fusion of the jock-nerd worlds. But few are more adored than Brian Lewis, better known as the Professor—a man often dressed, as you would expect, in a brown waistcoat and tie—whom I found walking between tables in the tournament hall. He was once as withdrawn and socially anxious and saved by Magic as many of the people who have come to the game through his now thrice-weekly dispatches on YouTube. His channel, Tolarian Community College, named after a fictional island in the Magic universe where a legendary academy tragically exploded, mixes consumer reports on proper card storage with debates about gameplay, reviews of new cards, and comedy skits with cosplayers. “I have more people subscribed to me than Wizards of the Coasts has subscribed to them,” he said, brushing his shoulder-length hair back behind his ears. “The actual company that makes the game has less pull with people than I do, and they hate me for it.”

To illustrate his claim, he pointed behind me to a young man toting a large, handled box. It was designed to carry screws, but the man had filled it with Magic cards. “I will bet you a thousand dollars he got that after seeing my video on it,” he said. (I tracked the man with the case down later, as he was ordering a sandwich: “One hundred per cent. I saw the video and, the next day, I ran to Home Depot after work and picked it up.”)

In 2013, after putting together a full-time schedule as an adjunct English professor at colleges around San Francisco, Lewis posted a video on YouTube, rating different brands of card sleeves. Two years and many videos later, the classes he was teaching were cancelled, his car broke down, and he posted a video called “I just lost my job. Can I have a dollar?” Many dollars flowed in. As we spoke, people started to gather around him, praising his advice and asking for hugs and for signatures on cards worth hundreds of dollars.

“We’re all freaks here, we’re all friends here,” he said, of the Magic community, as it surrounded him. “Many of us, we were bullied as kids. Most of us, we were excluded as kids. We know that feeling. And, you know what, we’re adults now, so the idea that somebody is not going to be able to play because of whatever, most people here reject that concept and say, ‘Come have a seat at the table.’ ”

In an old Usenet post on the history of Wizards, Adkison acknowledged someone who is today an overlooked figure in Magic’s origin story. Beverly Marshall Saling, the company’s executive editor, brought a lot of high polish to its early products, Adkison wrote. Like many of his colleagues, she was an old friend from his D. & D. playgroup. One of her jobs in Magic’s first sets was to edit the rules for clarity and to choose the quotations that lent the cards a fantasy “flavor.” A line printed below an image of a flying woman: “Four things that never meet do here unite / To shed my blood and to ravage my heart.” A rule: “Tap to destroy a wall.”

Beyond designing a well-worded world and a compelling look, Saling and Jesper Myrfors, Magic’s first art director, wanted to avoid the oversexed and Eurocentric fantasy motifs of the past. Early on, Saling encouraged the development of an Arabian Nights-themed deck to get more people of color in front of players’ eyes. “Shahrazad,” a spell from that set, forces players to start a second mini-game and is illustrated by a smiling brown-skinned woman lying in a tent. It’s Garfield’s favorite card.

“Beverly really trained me on a lot of these topics,” Adkison recalled. “Right from the very first game we made, you had different ethnicities and both genders represented in the example text. Wizards started on the right foot.” Garfield was proud of the illustrations that Myrfors got together, largely from art students in Seattle, many of whom had never painted fantasy art before. He also acknowledged that Wizards had occasional lapses. “From time to time, the women being portrayed are more sexualized than they were back in the day, but if you look at the first set of cards that was published,” he told me, “you will definitely not find any fur-lined halter tops.”

Saling’s motivations arose, in part, from her memories of the gaming conventions she attended throughout the eighties, where the people who sat down for role-playing games with her apparently had no stake in her discomfort. “They’d say stupid stuff, like, ‘Oh, you know, the girl characters have to make sure that they don’t get their periods, because the monsters will smell the blood,’ or, ‘Oh, you’re here because your boyfriend plays.’ And it’s, like, ‘How do you know he’s not here because I play?’ ”

When Adkison gave Saling the opportunity to help bring Magic to the unsuspecting world, she had a chance to make the gaming community a little more hospitable, or at least to try. Saling, Myrfors, and other liberal-minded employees at Wizards presented their social-justice sensibilities as more than moral; inclusivity, they argued, would open new markets. “We are not just going to make this for the usual suspects. We’re going to try to make it something women would like. We’re going to try to make it something people of color would like. We’re going to try to make it something that everybody would feel welcome playing with and would have a good time doing,” she recalled. “We pitched it as, ‘We’re going to be different than the rest of the industry.’ ”

Garfield was optimistic, but it wasn’t everything he hoped it could be. “When Magic first came out, I believed that by making something less objectifying to women, that women would flock to this new game experience. There was a lot of positive feedback from women, but it didn’t magically change the distribution of players,” he said. The “cultural inertia” was too much to overcome: “Just because we came out with one welcoming game, people weren’t going to suddenly start playing if they hadn’t felt welcome for their entire life.”

The company went through more philosophical growing pains after Sanders, Adkison, and Garfield trickled out over the next decade. In 1998, Wizards’ marketing eschewed “broad appeal” and narrowed its focus to “established gamers.” To a degree, the old ideals still held. An artist’s style guide, posted in 2005, included a general plea for diversity and an admonition that though “beautiful women” could, of course, be painted, they must be “kicking ass. No damsels in distress. No ridiculously exaggerated breasts.” Nevertheless, it also made clear what was meant by established gamers: “Remember, your audience is BOYS 14 and up.” In 2008, Wizards introduced an ad campaign called “Here I Rule.” Mel Li, the longtime Magic player, recalls walking into game stores and seeing posters “with a very angry-looking male figure surrounded by a bunch of demons.” She remembers thinking to herself, “This is not my personal experience.”

Some players who wandered in from other demographics and found Magic pulled up the slack. Tifa Robles started going to gaming conventions in 2008 and began playing Magic in 2010, and was quickly in its thrall. She founded the Lady Planeswalkers Society after women started approaching her to teach them Magic outside of the male-dominated game-store scene. Her experiences and motives reflected Saling’s. One year, after she attended a gaming convention called PAX, a friend alerted her to an alarming video of her on the Internet. “I was playing a video game and somebody had taken a camera and was trying to go under my skirt.” Later, while playing Magic at the game store where she worked, a man starting talking about her breasts. “Oh, you’re not wearing a bra today,” she recalled him saying. “And I was, like, ‘O.K.’ ”

Despite these experiences, her love for Magic and the Lady Planeswalkers Society only grew. Chapters started popping up across the country. In 2011, Wizards hired her first in customer service and, the next year, as an assistant brand manager. Soon she found herself advocating for gamers like herself from the inside. “While I was there, they consistently said, ‘Our audience is eighteen- to twenty-four-year-old men,’ ” she recalls. “And I was, like, ‘Why? Why are we limiting ourselves to this?’ ”

The pressure continued on the outside, too. Mark Rosewater, a Wizards employee since 1995, became Magic’s head designer in 2003 and started answering questions on Tumblr in 2011. By 2012, two-thirds of the principal characters that populated Magic’s fantasy world were men, and the community noticed. In a Tumblr post recently resurfaced by two Magic players, Rosewater told fans dismayed by these gender disparities that, although Wizards wanted its player base to change, Magic was male-dominated, and the art simply followed “the current natural gender skew of the game.”

The next year, two affable Midwestern comedians, Maria Bartholdi and Meghan Wolff, started a podcast called “Magic: The Amateuring,” which began as a record of the hosts’ attempts to learn the game and became a kind of “Car Talk” for Magic nerds. (No longer amateurs, they recently renamed the show “Good Luck High Five.”) Their podcast eventually reached less typical kinds of players. “We’ve had a lot of people come up to us and say, ‘Our daughter listens to this,’ or, ‘We listen to this together as a family,’ ” Bartholdi told me. But there were also detractors. As their audience grew, they watched abrasive comments pile up on Twitter, and then, around 2015, a number of female players, including Wolff, penned articles about the difficulties of being a woman in the Magic community. “To Wizards’ credit,” Bartholdi recalls, “they called us and said, ‘Hey, what can we do?’ ” Bartholdi and Wolff’s big suggestion: make women more visible.

Rosewater explained that he regretted his 2012 post, and, in 2013, he asked his Tumblr followers for advice on how to broaden Magic’s audience. Eventually, he came to realize that he wanted the Magic world to reflect not just the Magic community but the world at large, and he and his colleagues began to insure that the cards had a more equitable gender split. The company became more proactive in pushing the marketing mission that Saling and others envisioned at the birth of the game. Wizards hired Bartholdi to cover Magic tournaments, and it began hiring more women to work in game development, tapping top competitors like Jackie Lee and Melissa DeTora. Ironically, this meant Magic fans could no longer watch them climb the rungs at a tournament. “I think it’s a tough thing for any player, if Wizards is, like, ‘Would you like a job with benefits?’ ” Bartholdi said. “I think after enough time people will break, and they will be, like, ‘Yeah, I want health care.’ That’s just the sad reality of America, in general.”

In Las Vegas, Wizards and Channel Fireball seemed to be trying to tip the gender scales for future events by highlighting the women who had shown up at the convention center. Some of them found this special attention amusing. As I was wandering the stalls of Magic artists who sell prints and sign cards, I noticed two men with a large camera ask a young woman in a polka-dot dress and boots to show off her newly signed playmat. “When they asked me to do this video just now,” the young woman said, after the men walked away, “I was, like, ‘Y’all are catfishing, because there’s, like, ten girls here.’ ” It was a slightly exaggerated claim, and yet when I asked Bartholdi, she recognized the truth of it and complimented the effort. “You have to push it a little bit, because if you don’t, it will take longer,” she told me. “You have to see it to be it. Right?”

These strategies have shown some sign of sprout. Near the entrance of the convention hall, I spoke with Dana Fischer, an eight-year-old competitive Magic player, and her father, Adam, who once was a regular on the Pro Tour. Dana’s red hair flowed out from under a black Channel Fireball cap tipped to the side. As she explained that she wants more “young kids and women” to play Magic, a shy young fan, wearing black cat ears on her head, approached her. “Hi,” the cat-eared girl said, in the smallest voice she could muster, before skittering away.

Robles says she now feels comfortable directing women to game stores, more of which have begun anticipating female players. “Having a garbage can in their bathroom,” Bartholdi said, “it’s so small, but it goes miles for being a woman playing in a store.” Many people I spoke to in Las Vegas remarked on the unusual kindness of most of the Magic community. Despite the existence of digital platforms like Magic Online and the soon-to-be-released Magic Arena, many of them said, it was, at heart, a game done with paper cards at a table in physical space. Opponents could share eye contact, the oft-cited bedrock of empathy.

Though it’s a long way off, Rosewater told me that the game, at least in its strictly competitive form, is heading in an increasingly digital direction. This doesn’t worry Saling. “Online communities don’t have to be full of assholes. If your community is known for being welcoming and accepting, it helps. It doesn’t mean you don’t have to moderate the community; the company has a responsibility to not let the assholes take over. I think Magic people pride themselves on trying to be inclusive, and that’s what makes other people feel comfortable there.”

Recently, Magic has also tried to acknowledge its queer and transgender customer base. In 2013, game designers put their first nonbinary planeswalker on a card, and, two years later, introduced their first explicitly transgender character, Alesha, Who Smiles at Death. In Vegas, I came across Stephen Wooley-Broder, a man wearing a pink shirt emblazoned with a T. rex spewing a rainbow printed across the chest. He pulled a two-year-old card called “Kynaios and Tiro of Meletis” out of his backpack to show me. It depicts two soldiers in Roman-style armor, one white, one black, standing side by side. “My husband is half white, half black,” he said as he held out the card. “And it’s pretty obvious that they’re a gay couple. One of them’s running their hand through the other’s hair.” His husband, Lenny, ran up from another booth with an arm full of merchandise for Stephen.

Stephen and Lenny told me they both appreciate Wizards’ recent efforts to represent more diverse parts of its fanbase and to root out bigoted players. In the past, Stephen explained, he never experienced any outright homophobia, “but it just feels more comfortable. There’s less holding yourself back. Like, I feel very comfortable . . . ”

“. . . Wearing matching shirts today?” Lenny, who was also wearing a rainbow-breathing-dinosaur shirt, suggested.

“Yes,” Stephen said, laughing. “Or holding hands, or kissing, or whatever.”

As Wizards’ art directors and editors shift the illustrations and story lines that inflect each Magic card, they have inevitably drawn criticism. Designers have been reintroducing old characters or digging more deeply into their pasts, changing body size, or switching races, or not. Stephen told me about a planeswalker named Chandra who wields red mana and whose red hair is frequently on fire. “She’s from a plane that’s basically India if the British hadn’t invaded,” Stephen explained. “But she’s a white person, and all the other people in her plane are basically Indian, and it’s kind of weird.” Other players, part of what many tournament attendees in Las Vegas insisted were only a small but loud contingent, have been complaining about the shifting races and body shapes of their favorite characters and what they see as, contrary to Garfield’s inclination, too few erotically stimulating cards in recent sets. After the tournament in Las Vegas, I found slogans like “Make Magic Sexy Again” strewn across Reddit.

Chris Cocks, the Wizards C.E.O., said that he had taken notice of the difficulties around their diversity efforts. “In any kind of fandom, you have this natural tendency to be the last one into the clubhouse, to make it feel special,” he said. “What we remind people is the clubhouse is more fun the more people that are in it, the more diversity and styles of play that are in it.” They have fully embraced the company’s original inclusive ideals, and Magic players’ zeal for collecting different kinds of cards is matched only by the company’s desire to draw in different demographics of players. Recently, Wizards has also sought to insure that “gamers of all kinds” feel welcome at Magic events by banning several prominent players for harassment and bullying, especially online. When I asked Elaine Chase, a Wizards marketing vice-president and a Magic player since 1994, whether it was difficult to make such decisions, she was quiet for a few seconds and then said, “It’s difficult for me when I see people in the community not being treated with respect.”

Rosewater and many other people at Wizards, past and present, feel that pursuing inclusivity is simply the right thing to do, but one of the company’s goals with Magic, in promoting diversity, and everything else, is to get as many people as possible to buy cards and play with them, and then, when Wizards prints a new set of spells, to buy those cards, too. Getting more people into the clubhouse “allows us to invest more and make the game bigger and better and bolder,” Cocks told me. He compared the ever-flowing stream of cards that are released several times a year to blockbuster film releases. “We’re entertainers,” he told me. “And we want to entertain as many people as possible.”

Magic has always had at its root the draw of an ever expanding, not quite reconcilable web of rules, characters, and illustrations, and its fans fall back and forth between awed admiration and gripes about the simpler, good old days. I thought that Jon Finkel, as the top Magic competitor in the world, a co-founder of a college scholarship program for Magic players, a partner at a three-hundred-million-dollar hedge fund, and a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, might have a unique perspective on these issues. Even though one could look cynically on the twelve hundred or so new kinds of cards Wizards hoped would entice players every year, he suggested that these growing universes helped bond old and new players in a similar experience of discovery, the pleasure of only partly understanding and acting anyway, and learning a little bit more about how to do better next time. In other words, the joy of probability. “The truth is that a lot of the reason that Magic is still good is the fact that it changes,” he told me. “If they didn’t change Magic, I probably wouldn’t still be playing it.”

In Las Vegas, on the final day of the tournament, I watched Rosewater, the new de-facto face of the game, holding a microphone and standing in shorts and a vintage Magic T-shirt beneath a statue of Serra Angel, a sword-wielding winged woman who has been illustrated and re-illustrated on different cards since the dawn of Magic. Two young Magic fans, Robert and Dani, were getting married in the company of their friends, assorted tournament players, several game developers, and half a dozen cosplayers, including Karn, an eight-foot-tall time-travelling silver golem.

After the wedding I found that Karn had, inside him, a five-foot-seven-inch Swiss man named Dom Atlas standing on stilts. From within the suit, which he had made himself, Atlas extended Karn’s hand. I took one of his enormous fingers in my grasp and shook it politely. This was Karn’s first wedding: “It’s a very special moment for them, and a great honor for us, too.”

I bid adieu to the kindly time traveller and returned to speak with Rosewater. Many now see him as Richard Garfield’s heir and hang on his every word. In many ways, he can decide the future of Magic. It’s part of his job to look back at all the previous Magic sets, all eighteen thousand unique cards, and make sure they’re not repeating themselves. As he spoke, a small crowd formed. One young bearded man was literally shaking with excitement.

Rosewater seems purpose-built for the Internet, where he bravely fields questions from fans. In half a dozen years, he has answered more than a hundred thousand of them. “I’m on Tumblr, I’m on Twitter, I’m on Google Plus, I’m on Instagram.” Like Garfield and Saling, he knows he can’t manage this world alone. He said he loves YouTube channels like the Command Zone and Tolarian Community College, and podcasts like “Good Luck High Five.” “A lot of the major stars of Magic aren’t Wizards people. We try and support them,” he told me. “In some ways, our fans make the best content.” As he talked about the importance of inclusivity, a humanoid cat wearing armor and a green-and-white skirt milled around behind him. “We’re for cat people, as well,” he said, smiling.

A few weeks later, in a Tumblr post, he addressed a man dismayed by “blatantly non conformist depictions of men and women alike” on the latest Magic cards. But Rosewater was having none of it. No more hiding behind the skew. Diversity is good, Rosewater replied. More chance for insight. More hope that brilliance will shine through. Not every little piece of this endless game was designed for everyone. You can take from it what makes you happy: calculation, expression, or what you will. Likewise, when I asked him what he would want people to know who don’t play the game, he told me to set aside the thousands of cards, the quarter century of history, the many pages of rules. “At the heart of it, it’s just a fun little game,” he said. “You can walk in and go as deep as you want—it will get deep if you want to go deep—but you can also just go up to your ankles.”

Sourse: newyorker.com