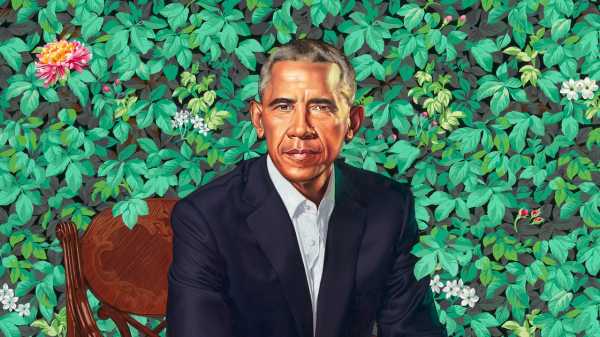

Obama is seated, the chair resting, one assumes, on a soft, unseen bed of soil. But the bottoms of his shiny black shoes simply float.

© Kehinde Wiley

I keep coming back to a bit of skewed perspective near the bottom of

Kehinde Wiley’s official portrait of Barack Obama, which was unveiled on Monday, during a ceremony at the Smithsonian National Portrait

Gallery, in Washington, D.C. The painting seats Obama—looking serious,

even slightly ruthless, around the eyes, but vaguely amused around the

lilting, half-upturned corner of his mouth—in a delicately detailed

wooden chair against a backdrop of bright leaves and vivid flowers. He

leans forward, his elbows on his knees and his forearms loosely crossed.

One cuff lines up perfectly with the other, forming a starched white

stripe, with a watch poking meekly through. In places—behind the former

President’s head, for example—the flora look flat, like designs on a

tapestry or a particularly adventurous wallpaper swatch: firmly in the

background, secondary to the subject. Elsewhere, the leaves assert

themselves as alive. One sprout seems to have worked its way, sort of

playfully, into the nook between Obama’s leg and the leg of the chair.

Another tendril brushes past one of the Presidential triceps. This kind

of dimensional ambiguity isn’t new to Wiley’s work; in “Napoleon Leading the Army Over the Alps,” a

large-scale painting that used to hang in the high-ceilinged front lobby

of the Brooklyn Museum, a damask of ovoid gold-on-blood-red occasionally

steals the foreground from the portly man astride his horse who is the

painting’s ostensible star. (His Timberland boots might be the funniest

touch in Wiley’s œuvre.) Leaves escape the backdrop of “Shantavia Beale II”

almost sneakily, threatening, it seems, to swallow the haughtily regal

Ms. Beale whole.

But look at the lower fifth or so of this newest—and, from here on out,

inevitably the most famous—of Wiley’s works. The feet of the chair

disappear into the brush, resting, one assumes, on a soft, unseen bed of

soil. But the bottoms of Obama’s shiny black shoes simply float. There’s

a similarly unanchored toe in Wiley’s “Judith and Holofernes,”

but the isolation of the murderous figure in that painting makes it

plausible that she has been rendered in one gorgeous dimension, made an

icon. The presence of furniture in the Obama portrait, feet in front of

feet in front of feet, is what creates a perplexing spatial puzzle. The

gesture poses questions that seem equally applicable to the meanings of

portraitist and President. Is this ecstatic realism or total fever

dream? A momentary slippage or a new stability? An exercise in

canon-making or sneaky deconstruction?

Wiley’s best works, whether backgrounded by brocade or a landscape

lifted from art history, seem haunted by a quiet uncertainty: Are these

depictions of black people, crashing the party of power as imagined in

the West, ironic, or meant to reflect some real and hoped-for future?

Yes, there’s comedy in the paintings, but is it the kind that ends with

a wedding or at the gallows? It’s possible to split Wiley’s corpus

fairly neatly in two—the much larger collection of portraits exalting

everyday, all-but-anonymous people, and those portraying a rich, famous,

and notionally powerful black élite: Michael Jackson, LL Cool J, the

Notorious B.I.G., and now Obama—and to wonder which subset is, at

bottom, more of a rueful joke.

FURTHER READING

Doreen St. Félix on Michelle Obama’s official portrait.

“What I was always struck by whenever I saw his portraits was the degree

to which they challenged our conventional views of power and privilege,”

Obama said at the ceremony. Many of the early tussles about

Obama’s legacy have had to do with the nature of his power and how he

chose to wield it. Consider Cornel West’s much-discussed broadside against Ta-Nehisi Coates, and, by extension, against Obama. Coates’s

interest in Obama has dealt, largely, with his symbolic power, both to

inspire and to disappoint, while West’s most powerful critiques of the

past Administration have centered on one of its frustrating paradoxes:

that, through his fairly conventional deployment of the more fearful

powers of the U.S. government—war-making chief among them—Obama proved

himself ultimately powerless to make radical, concrete change

commensurate with the message communicated by his face and his name.

Obama’s truest political gift, perhaps, was the ability to let a

thousand flowers of expectation, born of history, bloom. The flora in

the portrait represent the stations of Obama’s scattered personal and

ancestral past—blue lilies for Kenya; jasmine for Hawaii; chrysanthemums

for Chicago—and their momentary intrusions might hint at the ways in

which the man was somewhat shrouded by the dazzling story that delivered

him into his nation’s arms. He was hyper-visible and yet always partly

hidden. In Wiley’s painting, his face is all gravitas, that little smirk

notwithstanding, but—like George W. Bush, in his portrait before him—he

is tieless, his posture at least semi-casual. He’s the leader of the

free world, but also a guy you might know, taking it easy after work. As

President, Obama was exceptional and relatable; aloof and an empath; a

Bob Gates-style realist when it came to Syria and a Power-Rice

interventionist in Libya; a global celebrity and a ponderous professor;

a radical presence but somehow, simultaneously, a company man. I wonder

whether that balance, captured so well in Wiley’s portrait, will

persist. In the long run, history tips scales and issues verdicts. One

perspective or the other will last.

Sourse: newyorker.com