Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Susan Lorincz was essentially the local antagonist. She dwelled by herself in a rented dwelling in Ocala, Florida, situated on a street populated by young, working-class families. Children frequently spent time outside riding bikes, scooters, and roller skates, participating in tag or touch football, performing cartwheels on the lawns, and generating noise. The youngsters were primarily Black, and Lorincz, a Caucasian woman nearing sixty, viewed their typical playtime as a continuous offense, or a scheme to push her to insanity. She constantly berated the neighborhood children, whose ages spanned from toddlers to pre-teens. Repeatedly, Lorincz summoned law enforcement regarding them. “They shouldn’t be hollering and, like, running about,” she voiced to an officer responding one evening in August of 2022. Some months after, on another call to emergency services, she entreated, “Is there anything I can do concerning these individuals?”

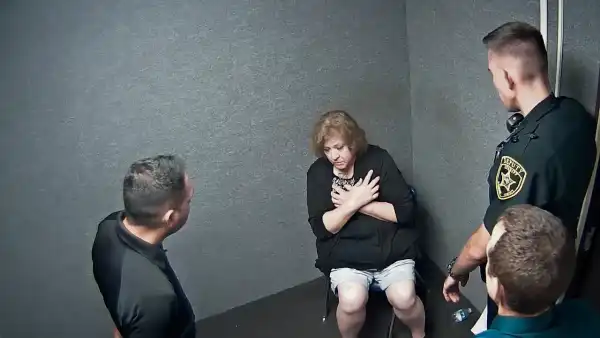

These interactions, simultaneously absurd and foreboding, are documented in Geeta Gandbhir’s unsettlingly gripping picture “The Perfect Neighbor,” which is crafted almost wholly from recordings captured by police body-worn cameras. (The motion picture debuted at Sundance and is currently transitioning to Netflix; the name originates from how Lorincz once depicted herself to regional authorities.) The subsequent year, during the evening of June 2, 2023, Lorincz—as was common—challenged several youths. She hurled roller skates toward a nine-year-old boy named Israel, who resided across the way; she might have also confiscated his digital tablet, and eyewitnesses noticed her waving an umbrella. Lorincz contacted the police, lamenting that the children were “leaving all their toys strewn about, just shouting, clamoring, behaving completely obnoxiously. . . . I’m fearing for my own well-being. . . . I’m simply exhausted of these kids.” Meanwhile, Israel informed his mother, Ajike Owens, regarding the dispute; Owens, understandably enraged, went across the thoroughfare to knock forcefully on Lorincz’s entryway and demand a conversation with her. Shortly after, Lorincz fatally shot Owens via the dead-bolted metallic entryway. Owens was thirty-five in age and a mother of four.

Four days elapsed prior to the police taking Lorincz into custody and accusing her of involuntary homicide. (She was subsequently found guilty and condemned to a term of twenty-five years incarcerated.) The explanation as to why such a lengthy duration was necessary—and the reason Lorincz was not accused of second-degree murder—was partly attributable to Florida’s Stand Your Ground legislation, which is extremely lenient regarding the employment of lethal force if an aggressor asserts that they acted defending themselves. It might likewise have been associated with ethnicity—Owens was Black, as are the children she bore. The implementation of Stand Your Ground statutes is generally most favorable to white individuals who shoot Black individuals; a study from 2013 demonstrated that “White-on-Black homicides were more prone to be deemed justifiable (11.4 percent) while Black-on-White homicides were least apt to be deemed justifiable (1.2 percent).” And Lorincz’s laughable claims that she was deathly frightened of the local offspring are demonstrative of research concerning the “adultification” of Black male and female children, who are commonly considered more mature and more culpable for their deeds in comparison to their white counterparts, and, as a consequence, are subject to elevated scrutiny and sanctions from educators, constables, and other supervising grown-ups.

“The Perfect Neighbor” recounts the ways in which Lorincz, through her efforts to convert law enforcement into adversaries of the people living within her own vicinity, succeeded exclusively in unifying the two entities in mutual revulsion. (I have not undergone such profound and intensely gender-charged detestation for a documentary shrew since “Dear Zachary.”) One officer, proceeding to his vehicle subsequent to attending to another of Lorincz’s urgent calls, mutters, “Psycho.” Nevertheless, despite Lorincz being regarded as marginalized and despised, she also displayed an extreme representation of our nation’s post-COVID mental state, a state portrayed by the informants, snitches, and paranoid citizens of Nextdoor and local Facebook discussion groups. These constitute the oddballs uploading footage obtained from Ring-style cameras depicting the suspicious-looking Cub Scout who dared to ring their doorbell; they are questioning if their neighbor’s sunflowers may be spying; they are considering telephoning the authorities regarding the adolescent who simply employed their driveway to rotate his auto, because that needs to be classified as illegal entry. Statistically analyzing, a large segment of these individuals possesses firearms.

Whenever children engage jointly in play, it “necessitates resolving some type of social conundrum,” the pediatrics scholars Hillary L. Burdette and Robert C. Whitaker articulated sometime in the past. The youths have to ascertain “the type of recreation, the permitted participants, the commencement and termination times, and the rules that oversee their interactions.” The collaboration and reciprocal exchange of play can facilitate “the growth of a spectrum of social and affective proficiencies such as sensitivity, adaptability, self-awareness, and self-discipline.” These represent the foundational components, the originators continue, of sentimental acumen. But, concerning the youngsters displayed in “The Perfect Neighbor,” the preëminent societal quandary was Susan Lorincz. And, within the surveillance state of twenty-first-century America, she is ubiquitous.

In the event that Lorincz appears distressingly typical, the neighborhood we behold in “The Perfect Neighbor” is increasingly atypical. Informal exterior recreation amongst youths has waned since the early nineteen-eighties, in spite of abundant substantiation of its merits concerning the physical wellness, executive-function capabilities, and communal interaction of youngsters. The grounds for the diminution are manifold and widely recognized; these comprise of parents’ statistically baseless apprehensions regarding abduction, heightened societal isolation, privatization of communal locales, municipal layout that favors autos and velocity over pedestrian accessibility and security, and the ascent of organized athletic programs. The sight of unaccompanied children playing or ambulating or propelling a bicycle gradually transformed into something conspicuous and, excessively frequently, instigated the intervention of constables or child-welfare representatives. Apprehensive parents withdrew their offspring even further.

Peter Gray, a psychology professor emeritus stationed at Boston College, has formulated a thought-provoking correlation between the depreciation of unstructured external play—play that is “unrestrictedly selected and directed by those involved and undertaken for its intrinsic value”—and a deterioration in the psychological well-being of children. Youths who consistently partake in unstructured play, Gray has transcribed, cultivate assurance and a sense of command through needing to arrive at conclusions and negotiate disagreement within their own ranks, absent the involvement or assessment of grown-ups. Such children are more predisposed to cultivate a robust internal sphere of influence, which renders them less susceptible to anxiety and depression at later stages of their existence. Gray emphasized that genuine unrestricted play is not centered around extrinsic objectives, such as earning an elevated mark from a teacher or impressing a soccer coach. The children represent the individuals decreeing their preference, and they perceive themselves as, to a degree, governing if and how they attain it.

A study conducted in 2021 determined, unsurprisingly, that “heightened parental impressions of neighborhood social integration also portended greater time in outdoor recreation.” This societal bond is profoundly self-evident in “The Perfect Neighbor.” The filmed material illustrates the effortless confidence and concurrence amongst the numerous parents, who seemed to possess a tacit pact indicating that the neighborhood principally belonged to the youths. They were granted a liberty to play and investigate that many of their counterparts in wealthier localities significantly lacked—or, rather, they would have been granted such liberty, if solely Lorincz had not regarded it as a forceful invasion.

During November, during Lorincz’s sentencing audience, her sibling provided credible attestation that Lorincz endured extreme maltreatment in her youth. Observing her sister articulate, I commenced to ponder if Lorincz was undone not solely by bigotry or mental ailment but by a passion of covetousness and dispossession—if what ultimately impelled her madness regarding her community was its constitution as a community, that her neighbors demonstrated care concerning each other and supervised each other’s progeny. At one juncture within Gandbhir’s presentation, a constabulary officer, amid questioning several of Lorincz’s young neighbors, pauses to inquire of a woman as to which assembled child materializes to be her own. Not one of the children’s caregivers is inherently present during that moment, yet the woman retorts absent vacillation: “They’re all mine.” She is joking in tone, but she means it in sentiment. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com