Americans, never mind their reputation, care deeply about art. They may not risk much for it, but they’re eager to believe that someone else would risk everything. If you doubt this, you only have to consider Chris Burden, the West Coaster whose sinister, bumbling stunts bought him a FastPass to fame, followed by a free pass for life.

People seemed a little afraid not to take him seriously, and seem so still. There he is in the September 2, 1973, edition of the Times, staring out from under a ski mask like a robber about to burst into a bank. He was only two years out of U.C. Irvine’s M.F.A. program, but already he’d fired a pistol at a Boeing 747 taking off from LAX; spent five days in a locker with two plastic bottles (one for drinking, one for pissing); and, on November 19, 1971, been shot in the left arm by a friend. The title of the Times article was, inevitably, “He Got Shot—For His Art,” although that was a little misleading. The plan had been for Burden to walk away with a scratch and a Band-Aid, and it was bad aim, not bold artistry, that landed him in the hospital.

Yet the legend of Burden the outlaw hero, willing to go all in on his performances, has proved ineradicable. He wasn’t the only American to make art from agony: in the seventies and eighties, there was a whole army of avant-gardists worrying the links between consumption and complicity, white-hot pain and chilly gallery-going. But Burden’s life and work had an oddly on-the-nose quality, which made him—along with Marina Abramović—the closest thing to a face the movement got. In the 2016 documentary “Burden,” every biographical detail glows with punk mystique: his renegade childhood, hopping from country to country; the time he broke the family television; his precocious relationship with pain, including a Vespa accident that landed him in the hospital with a crushed foot at the age of twelve. Even his 2013 survey at the New Museum, which emphasized his late, more sculptural work, was breathlessly received. Anything for the guy who took a bullet for the muse.

Ignore the legend, though, and you’re left with a career in which the despicable—the dangerous, sure, but also the puerile, cynical, and hypocritical—forms a thick manure from which only a couple of major art works bloomed. Burden’s most eloquent defenders, such as Maggie Nelson, have tried to quarantine the “good” works from the abominations, but abomination flows through pretty much all the early performances, only occasionally spicing them up. There’s an alternative world, one tiny rip away from our own, in which Burden electrocuted an unsuspecting passerby during “220,” the 1971 piece for which he lined an art gallery with plastic, flooded it, dropped a hot wire in the water, and perched on a ladder for six hours, accompanied by three other participants. In other worlds, Burden accidentally cracked a window on that 747, or caused a car crash on La Cienega Boulevard, in Los Angeles, or held a knife to a woman’s throat and threatened to murder her.

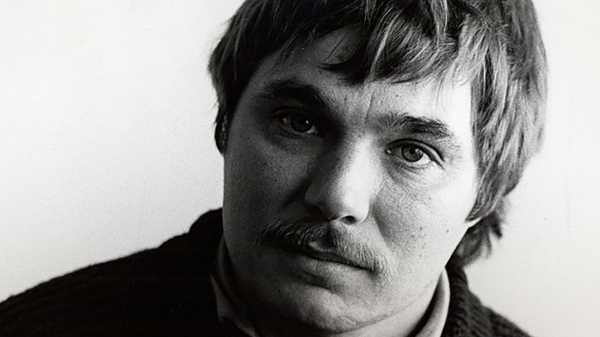

Photograph by Robert McKeever, Courtesy Gagosian

The last of those worlds, sorry to say, is the one we live in. The woman was a friend, the curator Phyllis Lutjeans, and in 1972 she invited Burden to stage a performance on a local TV station. Photographs of the result, “TV Hijack,” hang in “Cross Communication,” a new exhibition of Burden’s work at the Gagosian gallery, on Park Avenue. Burden grips his weapon in one fist and his victim’s hair in the other. Lutjeans looks terrified, something she’s confirmed in various interviews. She forgave Burden, though her grace seems inseparable from her faith that “TV Hijack” was a masterwork: as she says of the performance in “Burden,” “He was going to shift art history.” Whatever you think of Burden, his ambition can’t be denied. Walking through the Gagosian, which remembers twenty of his pieces made between 1971 and 1980, you see how big his appetite was; all the quintessential American toys are here (cars, guns, A-bombs), along with the major media of the era (television, photography, radio, the telephone). Still, when I look at the familiar forms of violence and tech on display, and at the unmistakable—because also rather familiar—agony in Lutjeans’s face, I can’t help but ask: shift art history to what?

The usual answer, paraphrased in a hundred textbooks, is: art that rubbed reality in its viewers’ faces, with “reality” defined as an endless series of hijacks, assassinations, and riots. Danger was the thing, and it came in every flavor: raw earnestness (Gina Pane pricking herself with rose thorns); sick suspense (Marina Abramović laying out saws and nails and inviting gallery-goers to do whatever they wanted with them); macabre daintiness (David Wojnarowicz sewing his mouth shut); sociopathic hideousness (Tom Otterness killing a dog). Burden’s art stood out in part for its primal simplicity. When Abramović incorporated fire into her work (“Rhythm 5,” 1974), it was a big razzle-dazzle: she cut her hair and fingernails, cast them into a flaming petroleum star, and then hurled herself into the middle, where she passed out for want of oxygen. When Burden used fire (“Fire Roll,” 1973), he just burned his pants and rolled around on them.

His great subject wasn’t violence so much as the way the modern media processed it. Whether he was inhaling water from a sink (“Velvet Water,” 1974) or covering himself with a tarp in the middle of the road (“Deadman,” 1972), he made nonsense of neutrality. He invited people to watch him, only to make them wonder why they weren’t averting their eyes—and also, maybe, how they could watch a protester getting tear-gassed on NBC and chew their dinner at the same time. Audiovisual records were as much the meat of these performances as the performances themselves. It’s easier to stand in the Gagosian and experience a six-minute film of a man gasping for air than to stand where it’s happening, but this doesn’t make “Velvet Water” the film a diluted version of Burden’s piece; the diluting, numbing effect of technology is half the point. (The people who witnessed it live could hear Burden, but they, too, watched on TV monitors.)

What these pieces have going for them, at their best, is tension. “Shoot,” the two-minute Super 8 film of Burden getting shot in the arm, manages to be striking and boring at the same time, the murky images humming with menace. I’ve seen it at least a dozen times and still can’t remember who stood on which side of the frame, what they wore, and what kind of place they were in, but that’s no insult; I can’t think of another work of art so vastly improved by its own visual blandness. “Shoot” refuses to be iconic. It travels straight to the pit of your stomach without lingering in your eyes, and by doing so it touches on something blunt and stupid about guns, as well as something magnetic. You’re repulsed, but only because you’ve chosen to keep watching.

In the course of the seventies, Burden switched from endurance stunts to cushier pieces for TV and radio. Yet the numbness persisted. The gambit of a pseudo-commercial like “Chris Burden Promo” (1976), in which the artist recites the names of five famous artists and then his own, isn’t so different from that of his earlier videos: deadpan humor has replaced deadpan horror, nudging you to fill the vacuum of emotions with some of your own. Plenty of postwar American art saw the electronic image as a hypnotic, unstoppable force. Much of it has aged poorly, and the very thing that set Burden apart from his peers—his emphasis on performance as media event, instead of performance as elaborate spectacle—now makes his work seem slight at times, even quaint. “I conceived a way to break the omnipotent stranglehold of the airwaves that broadcast television held,” he wrote, of his work for TV. “The solution was to simply purchase commercial advertising time and have the stations play my tapes.” Mission accomplished, but given that the stranglehold seems, in hindsight, barely a caress, it’s unclear why we should be wowed in 2023.

When asked why he kept getting himself hurt, Burden said, “I wanted to be taken seriously as an artist.” He had a point—this is the land where suffering is the ultimate badge of honor, whether you’re Sylvia Plath or Leonardo DiCaprio in “The Revenant”—but I can’t be the only one who finds his explanation cynical. It’s a weirdly passive idea, too, as though artists have no power to rewrite the rules, only to follow them. The notion that art isn’t an achievement so much as a transaction shows up too often in Burden to be accidental. When he pats himself on the back for buying airtime, he means that he’s just playing along: that America is a cold, technocratic place, and that his only chance of success is to out-capital the capitalists. In short, that the hand that stuck a knife in Lutjeans’s face was forced.

Maybe he really believed that. But, sometimes, an artist who thinks he’s holding a mirror up to the world ends up staring at himself. Surely it was Chris Burden, not the Vietnam-era U.S.A., treating human beings callously during “TV Hijack.” And was it the U.S.A., or just Chris Burden, who thought the big, bad capitalist market ultimately decides what’s important in art? “The thing I really like about that advertisement is that it’s true,” he said, of “Chris Burden Promo,” decades later. “If I had the ten million dollars or the hundred million, if I played that ad over and over, I would become one of those five names. . . . TV was so powerful that it would have made that happen.” This is obviously wrong—otherwise New Coke would be the national beverage and Michael Bloomberg would be President—but an artist can dream. Echoing below these performances, louder than any of their white-flag insights about violence and human nature, I hear the chuckle of a shrewd entrepreneur filling a hole in the market. Burden is often accused of masochism, but given what he implied about his fellow-Americans—those helpless sheep who do whatever the glowing screen tells them—that seems like his fans’ kink, not his. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com