11

This year’s broadcast of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, which has been televised since 1946, is expected to draw an audience of between twenty and twenty-five million people.

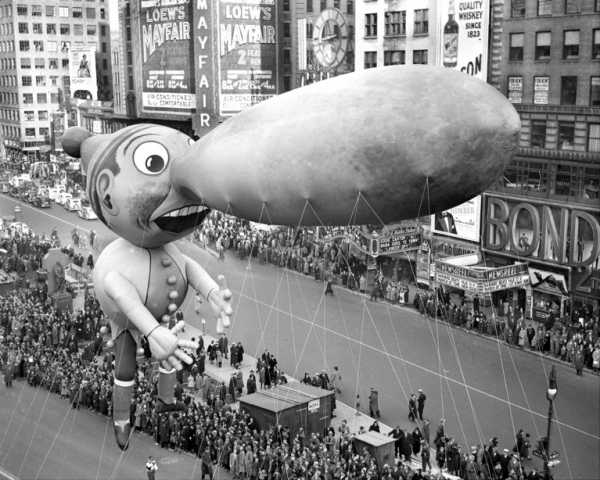

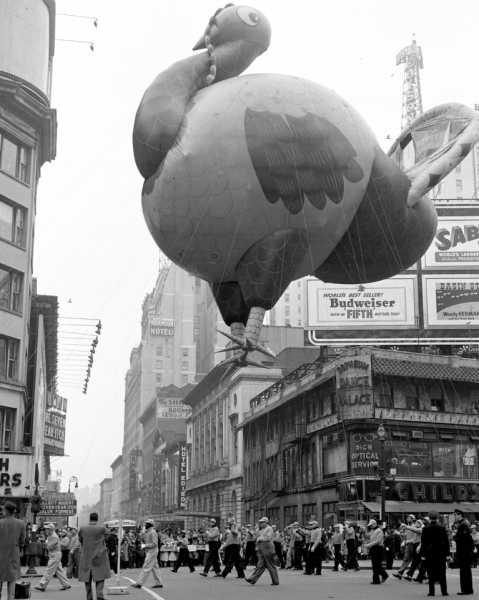

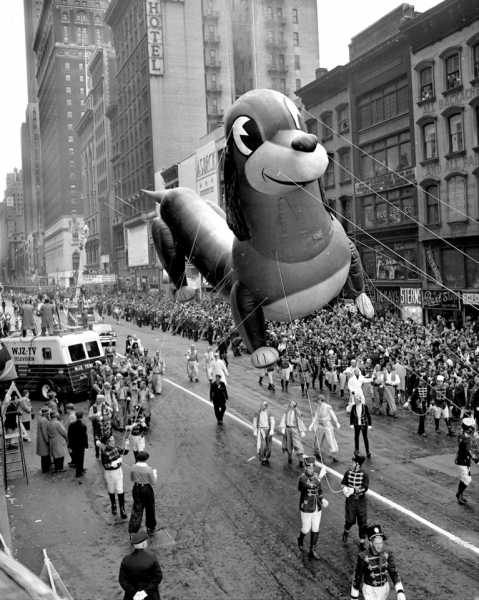

Photograph by Walter Kelleher / NY Daily News Archive / Getty

11Photograph by Al Pucci / NY Daily News Archive / Getty

11Photo by Tom Watson / NY Daily News Archive / Getty

11Photograph from Bettmann Archive / Getty

11Photograph by Nick Petersen / NY Daily News Archive / GettyFull-screen1 of 10

10

This year’s broadcast of the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, which has been televised since 1946, is expected to draw an audience of between twenty and twenty-five million people.

Photograph by Walter Kelleher / NY Daily News Archive / Getty

I strain to recall any particular detail from the Thanksgiving dinners served in my suburban boyhood, but the early hours of those careless Thursdays hover in my head as the image of a mass-cultural feast. A ceremonially decadent breakfast (Belgian waffle topped with a mound of canned apple-pie filling, a glistening glob of Cool Whip, and the beacon of a maraschino cherry) prefaced the all-American heap of processed corn telecast on NBC as the “Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.” My memories of the parade are not a distinct series of recollections but rather a steady procession of sensations that coalesce into a single high-fructose waffle drifting down a Broadway of the mind.

In terms of televised family entertainment, the parade is the biggest tent left standing. This year’s broadcast is expected to draw an audience of between twenty and twenty-five million people; about thirty per cent of U.S. televisions that are turned on will be tuned to this. I intend to turn it on and then to tune it out, mostly, while leaving my children to be inculcated by this monument to ephemera: My First Pseudo-Event. The broadcast trained very many of us in gorging on TV and submitting to spectacle—a mass-mediated semblance of community.

Advances in the parade telecast do not constitute a march toward progress so much as an exercise in keeping step with new expressions of the status quo. Variety reports that NBC will emplace Al Roker on a motorcycle outfitted with a camera rig “that will allow for 360-degree views,” and that the signature float—Tom Turkey, an animatronic fowl mounted by people dressed as pilgrims and, in these late days, accompanied by the serve-alongside stuffing of cooking-show celebrities—will be tricked out with new bells and whistles. But Tom Turkey is just adjusting himself to the contemporary palate, which will not taste the difference. The ancient show adapts to the eye of the times.

This year’s lineup of musical acts is a recipe for family-friendliness. Performers include a formidable pop belter (Kelly Clarkson), an immortal R. & B. diva (Diana Ross), a country singer/life-style brand (Martina McBride), a virtuoso of geniality (John Legend), a passel of pop acts unknown to adults, and a nostalgia act invited as if to remind the parents of the kids hooked by the pop acts to judge youthful follies of taste with great leniency (Barenaked Ladies). The harmonies will arrive amid visual dissonance, as when, last year, Patti LaBelle appeared on a float festooned with the Ocean Spray logo and escorted by people clad to harvest cranberries. Such is the bog we will wade in.

Marching bands will provide an authentic blare of inclusive American noise. Broadway casts will give a shimmer of Manhattan glamour. Balloons will rise above it all. My heyday as a rapt viewer witnessed the introduction of canonical cartoon characters including Woody Woodpecker, Garfield, and—a throwback to the nineteen-thirties that somehow spoke to the nineteen-eighties—Betty Boop. Later entrants, such as the mascot of the 1996 Summer Olympics and the spokesbee of Honey Nut Cheerios, were less distinguished. This year’s new balloons include a quartet of elves from “The Christmas Chronicles,” a new Netflix special which, improbably and yet inevitably, stars Kurt Russell as Santa Claus. In some respects, the parade is a thermometer calibrated to precisely read the temperature of popular culture at its dopiest. It comes by its kitsch honestly, and it is difficult to marshal cynicism in response to a procession which concludes with the arrival of Santa, even if one is skeptical of his existence. With its earnest hokum and its calculated salesmanship, the parade is meant to spark belief: in the TV as a kind of communal hearth, in a colonial holiday as a secular sacrament, in a pop pageant as a form of spiritual sustenance.

Sourse: newyorker.com