Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The bio-pic is a genre of extremes. The best ones share a uniquely powerful artistic authority, but merely ordinary ones are truly disheartening. The trouble isn’t only that of inflated prestige; bio-pics are disproportionately prominent during awards season and therefore ballyhooed nearly to oblivion. The form’s peculiar place in the art of movies is inseparable from the reasons for its exceptional prominence in the business. For producers and studios considering which projects to green-light, bio-pics check a lot of boxes. The protagonists are people who audiences are already familiar with and interested in. (J. Robert Oppenheimer may be the exception that proves the rule; he’s less famous than Freddie Mercury, but the atomic bomb is more so.) And the illustrious people who inspire bio-pics offer great showcases for actors. That attracts stars, which in turn attracts audiences. Bio-pics bathe the producers, the studios, and the filmmakers in the reflected renown of their protagonists’ achievements, and, because the enterprise inherently involves a good deal of research, it also conveys an air of studious seriousness. Presenting real-life stories as extraordinary adventures, bio-pics embody the axiom that truth is stranger than fiction. (Fear not: by the time Hollywood gets done with these lives, they’re rarely any stranger than the usual fictions, and may not even be that true.)

Nonetheless, the connection of bio-pics to ostensible reality is the hidden power of their success. If the makers of bio-pics freely elaborate (i.e., distort, bowdlerize, even falsify) the facts of their heroes’ lives, they don’t do so any more than the average Hollywood movie falsifies human experience at large, but they do so with an imprimatur of authenticity. With all the overt and tacit calculation that goes into the production of bio-pics, it’s something of a miracle that any of them are any good at all, yet indeed some of them are even great.

Perhaps the hardest thing about making bio-pics, at least ones regarding figures of actual greatness, is the inability of most directors to consider such heroes face to face, to share in the grandeur or the enormity of these protagonists’ inner lives. I’m reminded of an aphorism that I have long recalled as being written or said by Norman Mailer—please crowdsource me—to the effect that the one kind of character that no novelist can successfully imagine is a better novelist. I suspect that this inability, for novelists (and for filmmakers), goes beyond the limits of the artistic sphere to extend, over all, to exemplary achievers in any field. Most directors, like most people, have interesting observations about their daily lives, their communities, their fields of endeavor—and plenty of directors have, as artists, the practical skill to convey such observations. Part of the long-standing collective lament for the demise of the mid-budget dramatic movie—essentially, realistic movies featuring movie stars—is that it’s a form that even middling directors, writers, and actors have always done well. But bio-pics are different, because they are about extraordinary people, and fewer directors, writers, and actors are able to successfully imagine their way into this level of extraordinariness. The genre poses challenges of scope and psychology akin to the stringent visual challenges posed by musicals. Unlike with melodramas or comedies, it takes greatness to advance the art of bio-pics. The list that follows is thus also a parade of great directors.

It’s fascinating to see which great directors have chosen to make bio-pics (whether one as an exception or many as a habit) and what that choice reveals of their art. For instance, it’s no surprise that the history-obsessed John Ford made a bunch of excellent ones and that the extravagantly inventive Howard Hawks and Alfred Hitchcock did hardly any. It’s similarly logical that Kenji Mizoguchi, a relentless analyst of Japanese history, would make several, and that Yasujirō Ozu, mainly a storyteller of modern family lives, would make none. But it’s surprising that Satyajit Ray, whose films ranged widely through Indian history and society, didn’t make any, and equally surprising that Max Ophüls, an artist of ironic spectacle, did so to great effect; fascinatingly, in Ophüls’s vision of life as inherently a matter of theatrical pretense, the gap between fact (theatricalized) and fiction (exposed) closes. For Abbas Kiarostami, a real life based on falsehood proves an ideal laboratory for the fusion of fact and fiction. For urban folklorists and analysts (such as Spike Lee, Martin Scorsese, and Raoul Walsh) and for autobiographical portraitists and historians of style (such as Terence Davies and Sofia Coppola), the lives of others are naturally linked to first-person observations and modes of expression. For all these filmmakers, the project of bringing to life a person who has already lived means a confrontation not just with the particularities of that one individual but with the nature of personality—of character and human behavior—itself.

In compiling the list, I’ve set a few ground rules for myself: first, no approximations, only characters bearing the names of people who existed and did pretty much what’s seen in the movie. (In other words, no 1932 “Scarface,” however closely the character of Tony Camonte is based on Al Capone, and no “Citizen Kane,” which owes much to the life of William Randolph Hearst.) Also, I’ve avoided movies that are not centered on the life of a single character, even if they are based on true stories, such as “Zodiac”; there’s a difference, imprecise but meaningful, between a bio-pic and a historical drama. Moreover, no more than one film per director. I’m presenting these titles in chronological order, and, though I hope that you’ll get to see all of them in some way or another, I’ve selected them without regard to their current availability, whether streaming or on physical media.

Photograph from Henry Guttmann Collection / Getty

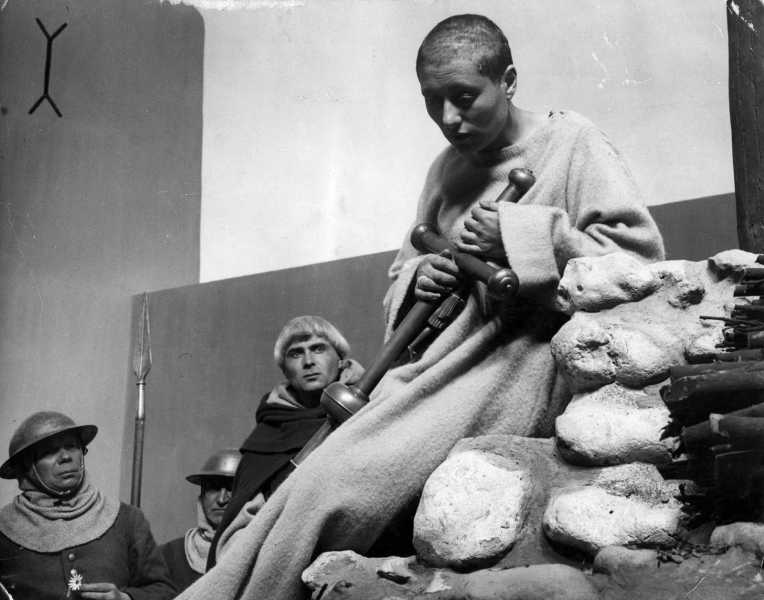

“The Passion of Joan of Arc” (1928, Carl Theodor Dreyer)

Ernst Lubitsch may have perfected the evocation of sound and music in silent films, but Dreyer, in this movie based on the trial transcripts of the medieval French national heroine, brings silent-film dialogue to its artistic pinnacle. The stark intensity of his images and the expressive clarity of the lead performance, by Maria Falconetti, give birth to an instantly avant-garde cinema that’s also a synthesis of the classical arts—a literary tragedy realized with the torque of theatrical artifice and a painter’s precision.

“Gentleman Jim” (1942, Raoul Walsh)

Errol Flynn has a rollicking good time portraying the boxer James J. Corbett, who rose to fame in the late nineteenth century for being as dashing and witty outside the ring as he was suavely powerful inside it. A poor San Francisco bank clerk and the son of a coachman, the amateur pugilist Corbett talks his way into high society at the moment that high society wants to render the low-life spectacle of prize-fighting respectable. The effervescent story tracks the brashly elegant boxer’s progress from waterfront brawls to the heavyweight championship—by way of the balletic footwork that was his signature maneuver—his courtship of a free-spirited heiress (Alexis Smith), and his surprising side business portraying himself onstage. Walsh—born in 1887, the year the action begins—films rowdy times rowdily, delighting in the teeming cast’s gimcrack manners and in the raffish early days of the modern sports business.

“The Great Moment” (1944, Preston Sturges)

The madcap champion of motormouth comedies seemingly veers weirdly off-course in dramatizing the career of the mid-nineteenth-century dentist named William Morton (played by the gruffly folksy Joel McCrea), who, despite opposition from doctors, pioneered the use of ether as an anesthetic. Amazingly, Sturges nonetheless presents the tale as a kind of screwball comedy, albeit one whose antics serve up a strong dose of homespun philosophy: The surprisingly far-reaching point is that so much of what matters in the world at large is the work of boastful dreamers with swollen heads, empty pockets, and fast-talking chutzpah; so much of what makes life sweet, or even bearable, comes from out of left field, by way of crazy coincidences that make screwball comedies feel like documentaries.

Photograph from Alamy

“Ivan the Terrible,” Parts 1 and 2 (1944-46, Sergei Eisenstein)

From visionary leader to battlefield savior and then paranoid tyrant, the mighty sixteenth-century tsar had—in Eisenstein’s lavish and tragic view—a destiny that paralleled that of Stalin, who got the idea and proved it by banning the film’s second part. Where the first part enthralls with its sumptuous, boldly composed images of power and its splendor, with majestic set pieces featuring armies of extras organized in mighty arrays, the second seethes with volcanic wrath and the abysses of madness, with eye-jangling color sequences to match. The performance of Nikolay Cherkasov, in the colossal and tormented title role, is one of the few in the history of cinema to rise to the level of history, period.

Photograph from Alamy

“A Scandal in Paris” (1946, Douglas Sirk)

Before becoming Hollywood’s double-barrel master of melodrama and Americana, Sirk was a European—born in Germany, raised there and in Denmark, and given a classical education. In Hollywood, where he went to flee Hitler (he wasn’t Jewish, but his wife was), he started with Eurocentric subjects, including this uproariously ironic biography of the French thief and fugitive Eugène Vidocq, who, in the turbulent decades after the French Revolution, became the Paris chief of police. George Sanders plays the glib dodger with wry panache as he simultaneously negotiates the underworld and the world of the élite. Sirk fills both of these picturesque realms with a spicy array of characters (and accomplished character actors to match) and delights in the intimate spectacle of a con man playing them like fiddles. But Sirk’s irony has a sharp political edge. The tale is also a vision of self-serving greed, self-destructiveness, and obliviousness, and it shudders with a sense of the director’s reflections on the forces that brought ruin to his European homeland.

“Utamaro and His Five Women” (1946, Kenji Mizoguchi)

Mizoguchi, one of the cinema’s most refined stylists, fuses his aesthetic with daring and far-reaching social criticism—largely involving the oppression of women in Japanese society. (For instance, even his epic historical drama “The 47 Ronin,” made during the Second World War, conceals its rebellious defiance in a tale of martial virtue and places a woman at its center.) The political realm is also inseparable from his view of the homebound story of Utamaro (played by Minosuke Bandô), an eighteenth-century artist who worked in the popular medium of woodblock prints, specializing in portraits of women. Mizoguchi’s vision of this commercial artist enduring official control and, ultimately, censorship—here concretized in the painful physical metaphor of hands being literally tied—suggests the agonies that come with the cinema’s public role, as well as the director’s view of the scathingly critical power of domestic art. And the virtually operatic story of one of the painter’s five subjects, a courtesan named Okita (Kinuyo Tanaka), who pays an unbearable price for illicit love, shows just how political Mizoguchi found personal life to be.

“The Actress” (1953, George Cukor)

This warmhearted, poignantly comedic drama about the actress Ruth Gordon is based on a play she wrote depicting her determination, as an impulsive adolescent, to pursue her theatrical vocation. And, along with its hearty sentiment, Cukor delivers a strong repudiation of provincial American moralism. Jean Simmons stars as Ruth Gordon Jones, born in 1896, a lower-middle-class high-school student in a small town near Boston. Her father (Spencer Tracy), a downtrodden food-industry employee, is pushing her toward a practical vocation, and her mother (Teresa Wright) hopes that she’ll settle down with a respectable Harvard boy (Anthony Perkins, in his first film). But, in defying her community’s prejudices regarding the lives of actors, Gordon provides a much-needed jolt that (no spoilers) unleashes a torrent of lurid backstory in her family circle and dispels hypocritical poses of virtue, principle, and decency. With humor and sentiment, Cukor and Gordon show that modern freedom is less a matter of doing things differently than of admitting what’s always been done.

“The Eternal Breasts,” a.k.a. “Forever a Woman” (1955, Kinuyo Tanaka)

Tanaka was one of the finest actresses of the golden age of Japanese cinema, working with such directors as Yasujirō Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. (She co-stars in “Utamaro and His Five Women.”) In the early nineteen-fifties, she also turned her attention to directing, and made masterworks—particularly this intense, intimate biographical drama, about the short-lived poet Fumiko Nakajō, who died at the age of thirty-one in 1954, soon before the film went into production. The poet’s sole consolation in a miserable marriage is her attendance at a local poetry club, thanks to which her work is published and quickly wins wide acclaim. She divorces—and is diagnosed with breast cancer, undergoes a mastectomy, and, knowing that she’s going to die, lives her remaining days in a bitter yet exalted burst of artistic and personal freedom. Tanaka films this tale of love and death with a confrontational, but also tender, frankness regarding women’s bodies, desires, and the distinctness of their art in a society that forces them into narrow attitudes and ways of life—a distinctness reflected in Tanaka’s bold cinematic style.

Photograph from Alamy

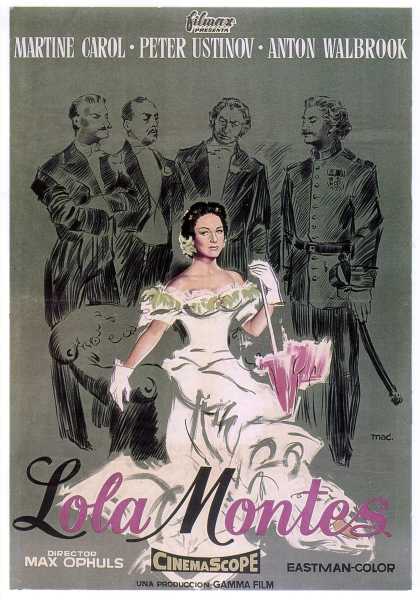

“Lola Montès” (1955, Max Ophüls)

The proof of Ophüls’s daring concept—a bio-pic about bio-pics—is that, soon after its release, the film’s producers drastically reëdited it, to the director’s great dismay. Ophüls died in 1957, and a restoration of his version was finally completed in 2008. It tells the story of a nineteenth-century femme fatale—a lover of Franz Liszt and of King Ludwig I of Bavaria—who overplayed her hand and, through reckless pride, ended up in a circus. A celebrity famous only for her past, she acted out sensationalized versions of her life and loves under a ringmaster’s crass and lurid narration. Ophüls presents the big-tent pageantry and the passionate drama of Montès’s life as similarly grandiose, gaudy, alluring, and tragic. In the title role, he shrewdly cast a tabloid-fodder star of the time, Martine Carol, and the actress lends Montès’s stoic air in the face of a disrespectfully indiscreet public a nearly documentary authenticity. (The genuine Lola Montez, born Eliza Gilbert, is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, in Brooklyn.)

Photograph from John Springer Collection / Getty

“The Wrong Man” (1956, Alfred Hitchcock)

A supreme fabulist whose works render lurid implausibilities irrefutably sublime, Hitchcock made one drama that sticks poignantly close to lived experience and, in the process, revealed the fictions on which ordinary life depends—for starters, the notion of innocence. In 1951, Manny Balestrero, of Jackson Heights, Queens, a musician in a night-club band, was arrested for a robbery that he didn’t commit, in what turned out to be a case of mistaken identity. Despite the story’s fine-grained realism, achieved through copious on-location filming, Hitchcock depicts the mind-bending power of the police and the judicial system with the sort of hectic and harrowing visual compositions seen in his more sensational thrillers—thereby raising a legal story to a metaphysical, quasi-religious plane. The revelation dawning darkly over the unfortunate protagonist—played by Henry Fonda with an aptly hushed sense of horror as the veneer of orderly reality is torn off—is that guilt may be the human condition.

Photograph from Alamy

“The Wings of Eagles” (1957, John Ford)

Sometimes it feels as if Ford, who saw all aspects of life in the light of history and politics, was in effect always making bio-pics. But, when he made them overtly, he let his real-life characters’ idiosyncrasies stretch and even rend his films’ rugged fabric. A prime example is this raucous yet pain-ravaged exposition of the life of Frank (Spig) Wead, a Navy officer who was among the pioneers of American naval aviation and who, after being paralyzed in an accident in the nineteen-twenties, became a novelist and a screenwriter (including for Ford). In reckless outbursts unrivalled in his long career, Ford presents the rowdiness of young recruits, the martial intensity of Wead’s medical treatment, and the incendiary conflicts of his marriage—Wead and his wife being played by John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara, uniting again in tragedy after the comedy of “The Quiet Man.”

“Jamila, the Algerian” (1959, Youssef Chahine)

The Egyptian director Youssef Chahine eventually became one of cinema’s great autobiographers, but early in his career he daringly took on a distinctive bio-pic subgenre: the story of a person who is still alive and involved in current events when the movie is made. He tells the story of Jamila (or Djamila) Bouhired, who, as an Algerian university student in the nineteen-fifties, joined the Algerian National Liberation Front and took part in its struggle to free her country of French colonial rule and establish its independence. Chahine dramatizes the political and paramilitary battles for Algerian freedom with an intrepid candor and a fearsome clarity; he shows Bouhired’s intellectual critique of the colonial educational system, and he depicts Bouhired’s life with family and friends in the light of that struggle—and of the dangers that shadowed her efforts, including arrest and torture. The movie shows her involvement with a plot to bomb a café and her trial for the act. Chahine films the story with uninhibited sympathy for the cause but without the inflated optimism of agitprop, and presents living history in all its complexity. (The actual Bouhired is now eighty-eight and lives in Algiers.)

“The Enchanted Desna” (1964, Yuliya Solntseva)

One of the most original figures to emerge in the early years of Soviet cinema, the Ukrainian director Aleksandr Dovzhenko, most famous for the movie “Earth” (1930), was alternately terrorized and rewarded by Stalin, personally bullied and coddled. When Dovzhenko died in 1956, he left behind autobiographical writings that his widow, Solntseva (who’d been an actress in the nineteen-twenties and worked closely with her husband for decades), adapted into biographical films. This one is anchored, daringly, in Dovzhenko’s bearing of witness to the destruction of Ukraine during the Second World War—and the joyful memories of his rural childhood there that his contemplation of the ravaged landscape brought to mind. Evoking her husband’s style, Solntseva fills the frame with overwhelmingly colorful and robustly choreographic images (shot on 70-mm. film!) of nature—a prelapsarian happiness before the Revolution—as well as awestruck and oppressive images of the rapid industrialization that, after the war, despoiled many of Dovzhenko’s beloved landscapes. The acting is bluff and hearty, but the real stars are the sunflowers.

“The Taking of Power by Louis XIV” (1966, Roberto Rossellini)

Rossellini’s lavish yet anti-spectacular analytical drama doesn’t merely show the iron fist of centralized state power sheathed in a velvet glove. Rather, the decorative glove and the panoply of accoutrements that go with it are themselves crucial weapons of the monarchy. The actors playing the King, his attendants at court, his aristocratic rivals, and even D’Artagnan and the other musketeers are relatively modest and effaced compared with the overwhelming splendors of fashion, cuisine, art, and architecture with which the King dazzled, intimidated, indebted, and thereby defeated the disloyal opposition. What emerges is a work of conceptual cinema with an enormous vision—one that reaches into the present day—in which the glories of French culture emerge as inseparable from the political essence of the French government.

“The Chronicle of Anna Magdalena Bach” (1968, Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet)

This meticulous depiction of Bach’s life and work, seen from the point of view of his second wife, emphasizes his modernity, and the enduring complexity of his work, by tracking his bitter conflicts with the authorities of his time. Forced out of an aristocrat’s service, he became a church composer and found his compositions criticized and his requests for financing often rejected. In short, he was like a filmmaker facing callous producers and an oppressive studio. Straub and Huillet convey his single-minded independence by shooting performances of his music in ways that make it anything but easy listening, as if restoring the challenging difficulty that it presented in its own time. They cast the harpsichordist and organist Gustav Leonhardt (one of the pioneers of historically informed performance practice) as Bach, and they filmed him and other musicians (including Nikolaus Harnoncourt) in extended single-takes that require as much attention and concentration from viewers as from the artists. Bach’s music emerges as an expression of resistance to artistic conformity, to the pursuit of facile popularity—a kind of resistance which the filmmakers themselves display in their severe sense of form.

“The Color of Pomegranates,” a.k.a. “Sayat Nova” (1969, Sergei Parajanov)

One of the great mystics of the movies, Parajanov, of Armenian descent and born in Georgia, was relentlessly oppressed by the Soviet regime. He spent years in prisons and labor camps, and his films were routinely censored or simply banned. He made this drama of the eighteenth-century Armenian poet and bard Sayat-Nova with the purpose (stated in title cards) of unfolding the artist’s inner life in images, and those teemingly detailed, boldly composed images are among the most startlingly painting-like and audaciously imaginative ones in the modern cinema—elaborate metaphors rendered as authentic physical experiences. The ecstatic effect is one of historical ethnography, a reanimation not only of the poet’s creative vitality but also of the vigorous, colorful, sensual, violent poetry of daily village life and ritual that surrounded him. The performances are choreographically, theatrically stylized and the images—complete with stark special effects—are decorated to the point of spilling out of the frame.

Photograph from Alamy

“American Hot Wax” (1978, Floyd Mutrux)

Mutrux, one of the unsung Hollywood heroes of the nineteen-seventies, made his third great film of the decade in the form of a rousing yet tragic portrait of Alan Freed, the d.j. who, twenty years earlier, had the taste and the audacity to play rock and roll on the air and to promote many of its early heroes in his boldly and diversely programmed concert series. Played with wry grandeur by Tim McIntire, Freed unites the musicians and their fans, and fosters new generations of both, in the face of official, racist, and reactionary opposition. Mutrux delights in the warmth of collaboration and the shock of inspiration, whether it comes from street-corner performances, recording-studio exertions, or the poetic ardor of on-the-air conversation. He films the action—musical and dialectical—with a sharp and sly sense of cinematic rhythm. Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Screamin’ Jay Hawkins play themselves.

“The Elephant Man” (1980, David Lynch)

In Lynch’s first studio film, he applies his uncanny sensibility to a historical subject and enacts a profound shift that’s as much a matter of perception as of emotion. The protagonist, John Merrick, an Englishman who lived in the Victorian era, had a disease that caused unusual and debilitating growths on his body and his head, and, as a result he was mocked and shunned, treated as a curiosity, and put on display in a circus. Merrick was doubly tormented by such mistreatment, as he was endowed with a sensitive personality and an artistic temperament. After a sympathetic doctor gave him shelter in a hospital, his refinement and his long-stifled creativity were increasingly acknowledged, and he counted an actress and a member of the Royal Family among his friends and benefactors. (The real-life Merrick’s name was Joseph, but he was called “John” in the doctor’s memoirs.) Lynch, his camera eye hypersensitive to the latent corruption and eerie menace of daily life, films an elaborately decorated period recreation as if from within Merrick’s mind, revealing the grotesquerie of the world that repudiates Merrick and the beauty that emanates from him.

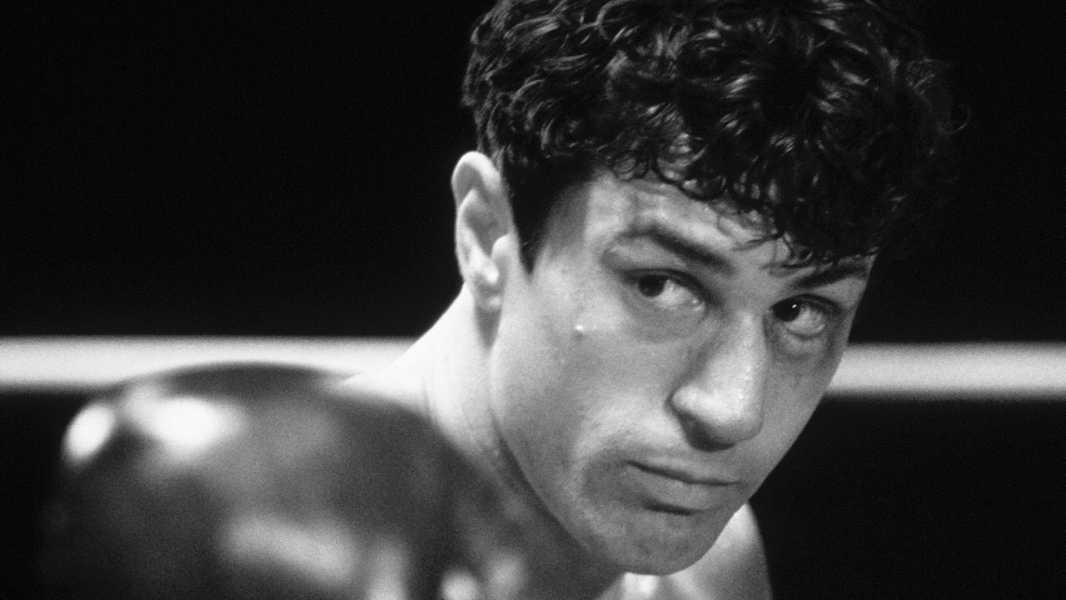

“Raging Bull” (1980, Martin Scorsese)

Scorsese may never have written a review in his life, but he’s nonetheless among the great film critics, as shown in his brutal and brutalized drama about the life of the boxer Jake LaMotta (for which Robert De Niro famously put himself through a calvary of physical ordeals, such as punishing training in the ring and dangerous extremes of weight loss and gain). Filming in black-and-white, Scorsese was not merely nodding toward classic Hollywood movies. Rather, this boxing movie is also a work of neoclassical reckoning, in which the invocation of predecessors from the studio era gives lie to the idea of a simpler golden age. The ostensible moral clarity of earlier times—and their cinema of good guys and bad guys—is revealed to be a veneer, concealing a sump of ills, among them racism, misogyny, domestic violence, and Mob rule. Scorsese looks at the past, including his own, and the gleaming myths on which it ran and which he grew up loving, and shows realities that were themselves not past but still appallingly current.

Photograph from Alamy

“Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” (1985, Paul Schrader)

This dramatization of the life of the writer Yukio Mishima occupies a key place in Schrader’s gallery of fanatics whose self-destructive obsession is also their glory. The movie is anchored in Mishima’s horrific and spectacular death: in 1970, leading a private army of followers in thrall to his brand of martial traditionalism, he took a Japanese general hostage and then killed himself by seppuku. Schrader intertwines events from the protagonist’s childhood, youth, and adulthood with scenes taken from Mishima’s own writings, which are filmed in highly stylized and brazenly artificial theatrical settings, and achieves the rare feat of finding a cinematic style to match a literary one. Moreover, the inner tension of that style inflects the rest of the film; Schrader’s spare image-making here reaches an apogee of lyricism, his sense of essential ornament appears forged in fire.

“Tucker: The Man and His Dream” (1988, Francis Ford Coppola)

The story of the automotive visionary Preston Tucker, who, in the nineteen-forties and fifties, attempted to compete with Detroit’s Big Three, building new kinds of cars and a huge new factory to produce them in, is a ready-made allegory for Coppola’s mighty and ultimately thwarted efforts to build a better Hollywood studio. The director takes to the project with dramatic verve and a visual exuberance inspired by the clean lines and huge scale of mid-century industrial design, as if the subject had brought out his inner “Fountainhead.” Anchored by the expansive yet poignant performance of Jeff Bridges in the title role, this tale of passion mocked and imagination denied—in which Tucker comes up against cynical journalists, ruthless corporate overlords, and coldhearted bankers—plays like Hollywood on wheels, complete with its headstrong challenger’s wicked speed and reckless thrills.

Photograph from Alamy

“Bird” (1988, Clint Eastwood)

Eastwood, one of America’s finest political filmmakers, relies on bio-pics as embodiments of ideas and ideologies. As a longtime jazz enthusiast, he offers distinctive insights into the life and art of Charlie Parker. Though Parker died in 1955, Eastwood’s insights are very much of the movie’s own time. In filming the agony of Parker’s life along with the sublime vehemence of his music, Eastwood—whose career-long directorial obsessions have centered on the failures of a cozy establishment and the dangers of demagogy—depicts the inability of the mass media of the time to recognize Parker’s historic greatness. Overlooked, underpaid, subjected to the unchallenged racism of the Jim Crow era, Parker also—in the ferocious concentration of Forest Whitaker’s performance—had a private vortex of self-destruction that was inseparable from the profundity of his musical mind. For Eastwood, the elevation of Parker’s life into an example and a myth (something that Parker himself resisted in his lifetime) is the movie’s overarching meta-story.

Photograph from Alamy

“Close-Up” (1990, Abbas Kiarostami)

No filmmaker has fused documentary and fiction as radically or as fruitfully as the Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami. Here he tells the bizarre true story of a man named Hossain Sabzian, a cinephile who dreams of being a filmmaker. Sabzian introduces himself to a family as the well-known director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, starts to involve them in a nonexistent movie project of his, and eventually ends up on trial for fraud. To this tale of fakery, Kiarostami adds an inspired twist: he casts Sabzian as himself, and the victims of the deception also play themselves, creating a kind of hyperreal hallucination in which the characters seen are simultaneously factual and fictional. Kiarostami shoots Sabzian with more than compassion: the director looks at the faux director with admiration that, while laced with irony, remains sincere. Sabzian’s skill at deception, imperfect but nonetheless sublime, comes off as a kind of art, and indeed a cinematic one, as proved by the film that results. Though Sabzian ended up in court (and actual footage of the trial is shown), for Kiarostami, the Supreme Court is cinema—an art that sits in judgment of all, including the judges, and that gets to a fuller truth than the law can.

“Jacquot de Nantes” (1991, Agnès Varda)

The director Jacques Demy, Varda’s husband, died in 1990, of AIDS. The following year, she made this biographical reconstitution of his childhood, based on his recollections, and centered on his precocious passion for motion pictures and his avid and accomplished work as an animator while still in school. The film, which features footage from Demy’s own homemade student films, is one of the most detailed evocations of the physical activity of filmmaking, and one of the great stories about growing up. Varda painstakingly reconstructs Demy’s boyhood—the daily dangers that he faced during wartime, under German occupation, and his relentless conflicts with his father, a mechanic who opposed his son’s artistic calling. This is also one of the few movies that’s a true love letter, filled as it is with intense, intimate closeups of the ailing Demy; his wrinkled skin and the screen seem to become one. The result is an embodiment of the idea of a shared life, as if Varda’s late husband’s past had also become her own.

Photograph from Archive Photos / Getty

“Malcolm X” (1992, Spike Lee)

Denzel Washington’s performance is so charismatic, multifaceted, and perfectly attuned to Malcolm’s true manner—without at all seeming like an impersonation or an imitation—that it would be all too easy to overlook the vigor, style, and uninhibited inventiveness of Lee’s direction, not to mention his daring and incisive script. (Lee also gives a slyly acerbic, antic performance as the younger Malcolm Little’s partner in mischief). Lee seemingly lives the history with every fibre of his being, and his meticulous yet florid mid-century reconstructions blaze with the power of spiritual devotion and righteous fervor along with their sheer dramatic energy.

“The Last Days of Immanuel Kant” (1993, Philippe Collin)

This historical film about the virgin philosopher is, paradoxically, the funniest movie on the list. Collin, who has spent much of his career as a critic, sees the aged Kant—played by the dourly puckish and gesturally exacting Samuel Beckett specialist David Warrilow—as a vital precursor to Jacques Tati or, rather, to Tati’s alter ego, Monsieur Hulot. The radical precision of Kant’s thought comes off as a product of the radical precision (or absurd rigidity) of his habits, which Collin nonetheless loads with pathos—as representing a quest for mental purity via the secular mortification of physicality. These are the oblivious yet graceful antics of a living ghost.

“Shulie” (1998, Elisabeth Subrin)

When is a documentary not a documentary? When it’s restaged, in its entirety, with actors. This brilliant work of cinematic reconception takes as its starting point a documentary about the writer, artist, and activist Shulamith Firestone, shot in 1967, when she was in art school and had yet to become one of the most prominent modern feminist theorists. The actress Kim Soss both replicates Firestone’s dialogue and inhabits Firestone’s persona, while the images, mimicking angles and subjects of the original, revel in subtle but unmistakable anachronisms. By replanting the 1967 artifact in the end-of-century soil, Subrin creates a historical montage that highlights the enduring force of Firestone’s ideas and how much has (and, tragically, hadn’t) changed in the interim. The result is a sharply discerning film of political psychology and social history, a lament for glorious futures past and lost.

Photograph from Alamy

“Marie Antoinette” (2006, Sofia Coppola)

A perfect pairing with Rossellini’s Louis XIV film, Coppola’s spectacularly ornamental yet melancholy tale is a vision of death by decoration. An exuberant and impetuous young spirit is confined in the luxury into which she was born, and then in the marriage and the court life into which she was effectively sold. The court consumed the wealth of France, starving its populace (who, of course, eventually rebelled) and, along the way, smothering its queen, who, in her way, also rebelled, albeit behind the walls of power. The film also casts an eye on the long-standing and long-unchallenged subordination of women to male authority, and it’s a crucial aspect of Coppola’s art that she is able to discover visual correlates—not to mention gestural, choreographic, and even musical ones—for Marie Antoinette’s narrow world and for her desperate quest for self-liberation.

“Talk to Me” (2007, Kasi Lemmons)

The director Kasi Lemmons brings a keen sense of swing and swagger—and a fierce sense of purpose—to the hearty, pain-seared, and cautionary story of the Washington, D.C., d.j. Ralph Waldo (Petey) Greene, a convict who, in 1966, used his gift of gab and unerring boldness to talk his way out of prison and onto the airwaves. Don Cheadle nearly bursts through the screen in the role of Petey; as the d.j. gives scathing yet exuberant voice to the state of injustice, historical tragedies loom, and Lemmons dramatizes grief and rage with noble passion. Then the enticements of the entertainment business come to the fore and burn Petey out—and this, in its clever and melancholy way, is the movie’s strange and deep insight. The energy of the storytelling—with other high-relief, invigorating performances by Chiwetel Ejiofor, Taraji P. Henson, and Martin Sheen—makes the film as irresistible as it is substantial.

“Nainsukh” (2010, Amit Dutta)

The eighteenth-century Indian painter of miniatures—a master of graceful portraits, fine-grained architectural views, assertive panoramas, and turbulent action—is presented here in a form that’s as much a matter of cinematic modernity as of classical echoes. Nainsukh, trained in his father’s workshop, rejects his father’s lessons and leaves home to seek both his style and his fortune. Dutta films the landscapes and the characters of Nainsukh’s life with an aptly painterly and lyrical manner, looks with rapt wonder at the hairline tracings of the artist’s preternaturally controlled brushstrokes, finds the artist’s greatest innovations inseparable from the freedom that he seeks in life, and spotlights the vehement conflicts (including with new patrons) that disrupt art and life alike.

“Cinema Verite” (2011, Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini)

A bit of an exception to the rule—because this life story is also a group portrait, and because it’s centered on an exemplary and mightily important work of modern cinema that is, dismayingly, all but unavailable in any format. The film dramatizes the making, in 1971, of the twelve-hour documentary “An American Family,” for which a production team embedded with the Loud family—a married couple and their five children—in Santa Barbara. The result offers a multilayered vision of the ethical risks of the transactional relationship of filmmakers and their subjects. The producer is played by James Gandolfini, in one of his most complex roles. But the movie is also very much the portrait of Pat Loud (Diane Lane), a stay-at-home mother who finds herself in the spotlight at the moment when she and the world are breathing the new air of self-liberation and also finding that lines of male and professional power remain in place.

Photograph from Alamy

“A Quiet Passion” (2016, Terence Davies)

It’s no surprise that Davies, one of cinema’s great autobiographers, was also one of its best biographers, as in this expansive, energetic, scintillatingly witty, and ultimately agonized portrait of Emily Dickinson—played, with puckish charm and tragic fury, by Cynthia Nixon. Dickinson finds relief from a stifling family life under her father’s stern order in her intellectually fulfilling friendship with a woman in her circle (Catherine Bailey)—and, especially, in her poetry, which met with opposition both at home and in the wider world. Then, the Civil War shadows the Dickinson family and the country; then the poet gets sick, and Davies films her terminal illness as a wrenching vision of pain (close in tone to that depicted in Ingmar Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers”) that’s as much a matter of spiritual terror as of physical torment—and that, above all, is a bitter lament for a life that she left largely unlived.

“Jeannette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc” (2017, Bruno Dumont)

The most exciting outburst of creative inspiration in recent cinema has been Dumont’s, ever since he propelled himself into freewheeling comedic and sociological inventiveness with the three-hour-plus “Li’l Quinquin,” in 2014. What he discovers in the childhood of Joan of Arc is deeply rooted in the details of history, yet also untethered to anything but the uninhibited wonder of his inner visions—which fuse with the heroine’s holy vision of worldly liberation. This bio-pic (the first of Dumont’s two films about the doomed and sainted warrior) externalizes the wild subjectivity of her religious devotion in the form of a rock opera, based on plays by the Christian mystic poet Charles Péguy (1871–1914). Filming on location in France’s rural north, Dumont devises images as ecstatic, in rapturous natural settings, as Carl Theodor Dreyer does in starkly theatrical ones. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com