Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Two days after the Syrian despot Bashar al-Assad fled his palace, Moises Saman and I arrived in Damascus to witness the beginning of a profound reckoning. The Assad family had dominated the country for half a century, culminating in a dozen years of civil war. Now a long campaign of internal violence had suddenly given way to an edgy, surreal peace, as Syrians took stock of the conflict that had dominated their lives for so long. Around Damascus, entire neighborhoods lay razed and depopulated, and much of the city center looked dingy and worn. In the suburbs, bombing campaigns had stripped residential buildings of everything that once made them homes.

In a basement beneath the Mezzeh airbase, in Damascus, the regime held opponents in cramped, windowless cells. The facility was notorious for its brutal treatment of prisoners. Among those imprisoned and tortured there was the noted activist Mazen al-Hamada.

Handcuffs dangle from a cell door at the Mezzeh airbase.

A torn poster depicting President Bashar al-Assad, in Damascus.

The Palestine Branch security complex, in Damascus, has become synonymous with torture, disappearances, and inhumane conditions. Survivors’ accounts describe hideously packed cells, relentless interrogations, and systematic abuse.

Along with the physical evidence of violence, there was a less obvious register of human loss—a phenomenon that Moises observes with singular sensitivity and skill. In the past two decades, he and I have reported together on a series of conflicts. After the collapse of the dictatorships in Iraq and in Libya, we found abundant proof of their brutality. But Assad seems to have been distinctly vicious. In 2012, as Syria descended into violence, Moises and I travelled to Aleppo with a crew of insurgent rebels and caught an early glimpse of the war’s horrors. At the time, we were appalled to learn that some twenty thousand Syrians had died. Twelve years later, estimates of the dead range as high as six hundred and twenty thousand; another fourteen million people, more than half the country’s citizens, have been displaced from their homes.

Motasem Kattan, a former detainee in the Palestine Branch, reënacts his ordeal, as his father looks on.

A torture implement found in the basement of the Al-Khatib prison, operated by Syrian intelligence services. The prison, in a middle-class Christian neighborhood of Damascus, was concealed from view—but people who live nearby say that they sometimes heard the screams of detainees.

At the morgue of Al-Mujtahid Hospital, in Damascus, the body of an inmate from Sednaya prison lies on a gurney. The man was executed and his eyes gouged out.

Sednaya, north of Damascus, is one of the most notorious detention facilities in the world. During the war, the regime held countless activists, political prisoners, and civilians at Sednaya, where they were subjected to starvation, torture, and extrajudicial killings.

In the field, Moises is restless and relentless, working from early morning till late at night with a professional’s calm. But his eye is unfailingly compassionate, and at times his scenes can summon the power of a religious tableau. On our trip in 2012, we visited a village outside Aleppo, where he photographed a mother mourning over the tortured body of her dead son. Her face, with empty eyes cast to the sky, summons a grief as old as time.

Boys wait for bread at a bakery in Douma, on the outskirts of Damascus. Once a bustling city, Douma has been ruined by years of combat and siege. Amid the rubble, residents struggle to rebuild their lives.

The images from our recent trip offer stark testimonials of the cost of Assad’s rule: the prematurely hardened faces of boys waiting to buy bread for their families at a bakery on Damascus’s outskirts; the ghastly visage of a murdered man whose killers had gouged out his eyes; the painfully legible despair of Majida Kaddo, whose brother-in-law, the activist Mazen al-Hamada, was detained and tortured for years, only to be killed just days before Assad’s fall.

Cars drive through a rubble-strewn street in Jobar, in eastern Damascus. In 2013, the regime reportedly deployed sarin gas against the civilian population there—part of a series of devastating chemical attacks in the surrounding area that year.

Worshippers gather in the courtyard of the Umayyad Mosque for the first Friday prayer service since the fall of the Assad regime. Also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus, it is among the oldest surviving monumental mosques in the world.

Tasmeen Khalid, age fifteen, holds her seven-year-old brother, Mohammed, in front of their makeshift home amid destroyed buildings in the Yarmouk Camp, a historic settlement for Palestinian refugees in Damascus.

A man stands in a graveyard damaged by bombing, in Jobar, one of the most heavily contested areas during the civil war.

Most of the Syrians we met had lost close relatives to the gruesome detention centers run by Assad’s regime. Moises’s photographs catalogue the workings of a vast state-security apparatus: a cutting tool used to torment prisoners; the fastidious filing systems of the torturers. One especially poignant image depicts a young man named Motasem, who spent fifteen months in the dungeon of a notorious military-intelligence prison—the so-called Palestine Branch—before the rebels freed him. In the photograph, he visits the prison and reënacts one of the humiliations he endured. “It was not only an act of memorialization but also a declaration of survival,” Moises said afterward. “To re-create those horrific experiences permitted Motasem to recover some measure of agency over an experience in which he had lost all control. At the same time, each movement evokes the fear and despair and endurance that defined his experience as a prisoner. Motasem’s courage in returning to that place serves as a reminder of the power of the human spirit in the face of unimaginable cruelty.”

At a funeral ceremony for the activist Mazen al-Hamada, hundreds of relatives and sympathizers gathered to mourn and to project solidarity. His sister-in-law, Majida Kaddo (center), was unable to see him for years, before his remains were discovered near Damascus.

Hundreds of mourners march through Damascus during the funeral of Mazen al-Hamada. After being imprisoned for pro-democracy activism, Hamada was forced out of the country. He returned in 2020 and was quickly arrested again.

Mazen al-Hamada’s grieving family members receive visitors at their home. At center are his older brother, Fawzi, and Fawzi’s son, Jad.

Many Syrians we met told us that their loved ones had simply vanished. They were presumed dead, flung along with countless others into the mass graves dug across the country. At one grave site we visited, surrounded by farmland near Damascus’s international airport, Moises photographed a long trough, which the regime had dug preëmptively to accommodate its intended victims. Several other troughs appeared to have been already filled and bulldozed over. How many hundreds lie there? A man who lived nearby told us that he had often seen refrigerated trucks come and go, but he knew better than to ask questions.

In an office at the Palestine Branch complex, desks are scattered with papers left behind by fleeing security officers. The documents, many marked with official seals and coded notations, contain clues to the regime’s atrocities. Some detail arrest orders and interrogation transcripts, and others bear the names of prisoners or records of surveillance operations.

Visitors to the Palestine Branch found photographs of prisoners, likely taken during intake procedures or interrogations. For many detainees, the expressions captured here—some staring blankly at the camera, others visibly afraid or defiant—may be the only remaining trace of their existence.

In a detention center at the Mezzeh airbase, abandoned documents contain records of a meticulously maintained system of repression, with names, dates, and accusations scrawled across the pages.

Dozens of bodies recovered from a mass grave on the outskirts of Daraa are stored in a morgue in the town of Izra.

As Syria contends with the concealed horrors of the Assad years, there are many bodies still to be recovered and mourned, many stories yet to be told. In a reminder of the moral vacuousness that typified Assad’s rule, the former dictator apparently issued a statement on the messaging app Telegram, a few days after arriving in Russia, where Vladimir Putin had offered him a safe exile. He claimed that he had abandoned his homeland only because his Russian allies had urged him to, and that his long war against his own people was actually an effort to restrain “terrorism.” He described himself as the “custodian of a national project, supported by the faith of the Syrian people, who believed in its vision.” Around Syria, this delusion has become impossible to sustain. The statues of Assad and the posters of his face that adorned every public building lie on the ground, toppled, torn, spat and stomped upon, finally susceptible to his citizens’ loathing and contempt.

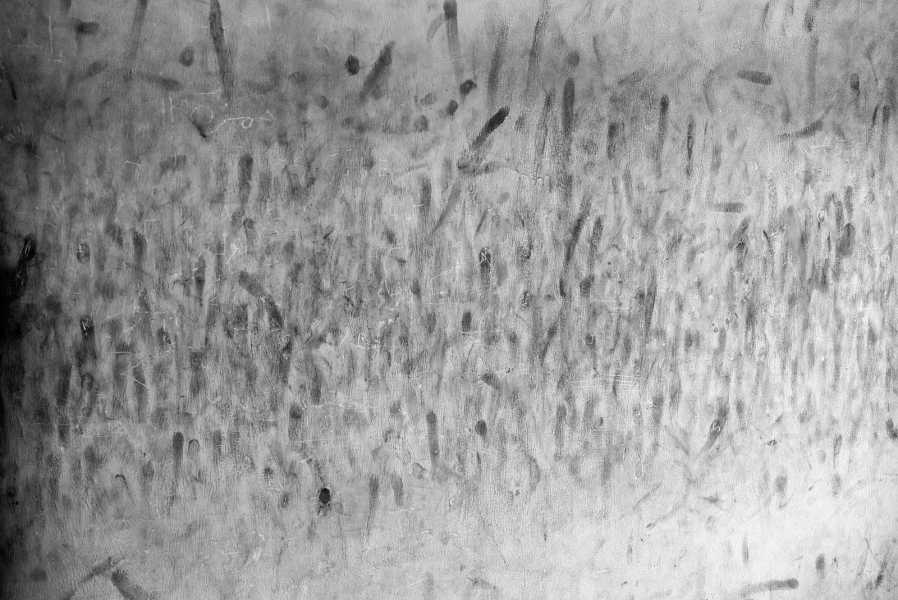

Smudged thumbprints cover a wall in the Palestine Branch, left by detainees going through registration or identification procedures.

Sourse: newyorker.com