The modern cinema of the sixties and beyond is a photographic cinema, recalling the highly inflected images of silent movies in order to affirm the personal touch, the omnipresence of the filmmaker as more than an unobtrusive transmitter of reality or mere stager of the script. The German director Ulrike Ottinger, one of the crucial modern filmmakers (and unfortunately one of the least-known), is also an exemplary photographic creator, as seen in the selection of her still photographs that are on display, until March 3, at Bridget Donahue, and in her movies (from which most of the images are taken)—particularly two that she’ll be presenting at Metrograph in the next few days, “Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia” (1989) and “Ticket of No Return” (1979).

When “Johanna d’Arc” had a weeklong run at MOMA two years ago, I wrote about the mighty substance of Ottinger’s brazen stylization—the combination of the dashing adventure, the ethnographic devotion, and the quest for self-definition that her flamboyant and exquisite aestheticism embodies. (In addition to directing and writing the script, Ottinger does her own cinematography.) For Ottinger, the play of imagination is an essential realm of freedom, a way for women to defy and liberate themselves from the misogyny that’s embedded as deeply in consensus styles as in consensus politics. She does something similar in the earlier film—albeit in a more local and explicitly sociocritical vein.

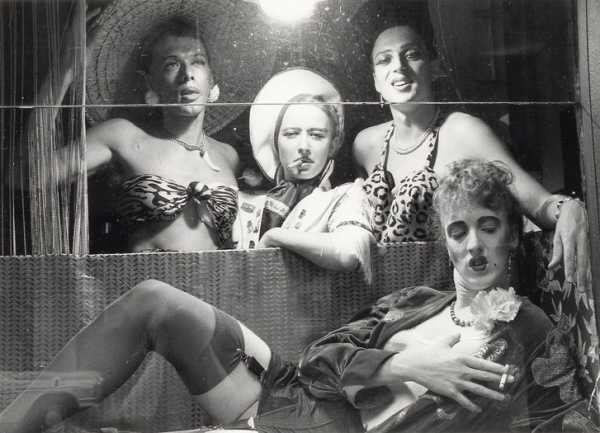

“Go—Never Back,” 1979, from the film “Ticket of No Return.”

The original, German title of “Ticket of No Return”—“Bildnis einer Trinkerin” (“Portrait of a Female Drinker”)—points clearly to the subject of the film and highlights its protagonist. An unnamed woman—young, cynical, world-weary, and described as possessing a stifled heroism—travels to Berlin (which is to say, West Berlin, divided at the time by the Wall) to “follow her destiny.” The woman is played by Tabea Blumenschein, a multifaceted artist and a real-life diva of Berlin nightlife. In a voice-over, it’s said that “Her passion was to drink, to live in order to drink,” and the woman parodies a simple tourism brochure in following, step by step, her self-devised drinking tour of the city—in order for her to live out to the ultimate extreme “a narcissistic pessimistic worship of loneliness.”

“The perfect image and its unrelenting mechanics,” 1977, from the film “Madame X.”

“Jacob’s Pilgrims,” 1981, from the film “Freak Orlando.”

The Drinker, clad in a splashy red suit and hat (only the first of her many colorful and sharply styled outfits, all designed by Blumenschein) arrives in Berlin’s airport along with a trio of gray-suited technocrats: three women named Common Sense, Accurate Statistics, and Social Issue, all of whom follow the Drinker throughout the film to deliver rationally moralizing critiques of her behavior (declaring that the “emancipated woman” is apt to drink too much). Conversely, technological modernity baffles the Drinker, as reflected in Ottinger’s sumptuously graphic, furiously expressive cinematography, with the cold comedy of her Tati-esque views of the gleaming airport corridors and the alluringly alienating forms of its metallic accoutrements, through which the red-clad Drinker strides with a theatrical bravado.

“Die Kalinka Sisters,” 1988, from the film “Johanna d’Arc of Mongolia.”

The film is filled with the Drinker’s episodic adventures high and low—inviting a street woman into a luxurious café and befriending her, getting thrown out of the café, and making local news for her antics; drinking champagne in a theatre under women’s disapproving stares, finding a mambo party in a lavish salon, getting fired from a job as a receptionist for drinking the boss’s fancy wine on the job, and taking part in an outdoor circus hard by the Wall. (It’s apparently ill-advised to try tightrope-walking while drunk.) The Drinker continues to pursue her determinedly reckless rounds in more lavishly eye-catching costumes ranging from a tight white dress with red buttons to a flowing chrome-silver gown, and Ottinger films her wanderings in images of a bold compositional floridity, rendering in richly textured detail the constellation of pill-like lights in the café, the grungy garbage-strewn industrial waterfront, the silvery chill of a whale-shaped riverboat.

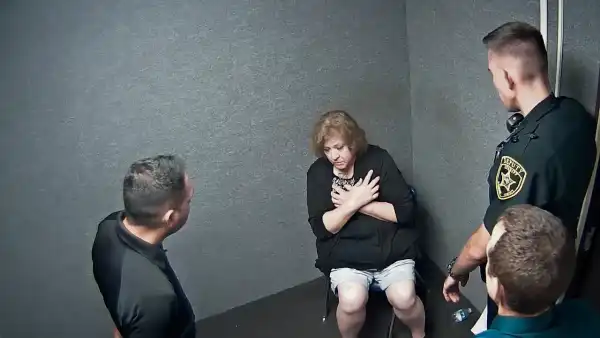

“In the oceanic brothel,” 1975 from the film “The Enchantment of the Blue Sailors.”

The modern cinema, with its photographic sensibility, also reconfigures cinematic performance, shifting the emphasis away from the novelistic psychology of characters to the gestural iconography and visual presence of actors. (The characters serve rather as guides: following the Drinker quasi-documentary-style, Ottinger offers a visual catalogue of Berlin sites and moods.) Emphasizing modes of self-dramatization, the director elicits performances of extravagant theatrical exaggeration (which also include scenes of pure theatre, such as several cabaret performances of songs, spun out in taut long takes).

“Café Möhring: reflection in the mirror,” 1979 from the film “Ticket of No Return.”

Blumenschein’s revelatory performance captures the Drinker’s energetic, contemptuous self-degradation in arch and precisely timed gestures, and accompanies her gleeful and self-scourging haplessness with self-aware winks, as if at an unseen observer, that are reminiscent of Lucille Ball’s mannerism-repertory. The Drinker’s debasement is also a form of exaltation; her mishaps are also her glory. There’s a crucially feminist tone and import to the movie’s higher loopiness, which is reminiscent of that ofcomediennes such as Ball, Gracie Allen, and Judy Holliday, the films of Elaine May, or the performances by Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier in Jacques Rivette’s 1974 film “Céline and Julie Go Boating.” As a street woman tells the Drinker, “Society doesn’t want us, madam; they drove us nuts, but I don’t want them either, madam.” Ottinger’s leap of absurdity is as much an expression of the tangle of confusion into which women are driven as it is an explosion of pent-up defiance at a repressively rational order. It’s a smiling rage at the idea that anyone should find the notion of women’s emancipation, or, simply, equality, anything other than self-evident.

“Dorian Gray,” 1983 from the film “Dorian Gray.”

Sourse: newyorker.com