Save this storySave this storySave this storyYou're reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we're watching, listening to and doing this week. Sign up to get it sent to your inbox.

Stan Douglas is a remarkable, singular artist who doesn’t try to demonstrate his importance with flashy statements or press releases about how his many films and photographs should be viewed through an autobiographical lens. Instead, he subtly explores and analyzes images that powerfully convey the poignancy of existence, especially when history disappears from our lives. The 64-year-old artist, who was born in Vancouver, where he continues to live and work, has dedicated his artistic career to creating art based on the experience of storytelling—all those stories that, as Joan Didion once said, we tell ourselves in order to survive.

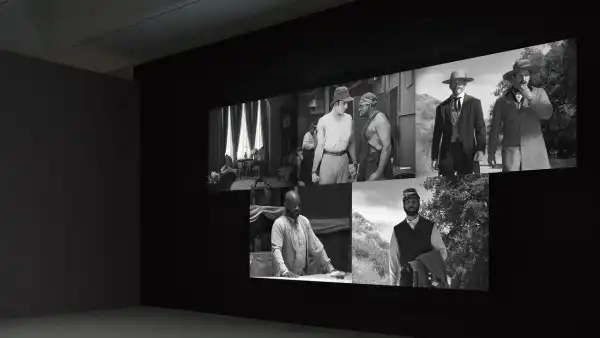

Installation view of Birth of a Nation. Work © Stan Douglas / Courtesy of the artist / Victoria Miro / David Zwirner; Photography by Olympia Shannon

In his remarkable and ambitious exhibition “Ghostlight” (on view at the Hessel Museum of Art at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, through November 30), curated by Lauren Cornell, Douglas creates a space that describes and hosts the agency of people from all walks of life, shaping a narrative that exists within and beyond comprehension. We don’t realize why we need stories to live, but we do, and Douglas underscores this in several standout works, such as his 1995 adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s classic fairy tale “Der Sandmann.” The installation references not only Hoffmann’s gothic atmosphere of fear, love, and the nuances of memory (Douglas created it in Berlin after the fall of the Wall), but also another important theme for the artist: how we represent what we remember. Shot on 16mm. The ghostly, black-and-white Sandman was shot at the old Ufa Studios near Potsdam, the company that distributed Leni Riefenstahl’s films, and depicts a landscape that evokes death and rebirth. In the intersecting videos, Douglas aims in part to tell the story of the Schrebergarten, a 19th-century urban plan that allowed the poor to grow their own gardens on small, rented plots. There are echoes of Syberberg’s Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), particularly in the director’s use of grey, hovering somewhere between black and white, but Douglas’s work is not operatic – it combines the mythical and the everyday in a single frame.

We experience history moment by moment, and one of the marvels of cinema is its recreation. However, Douglas does not approach cinema as a documentary, but as a document about storytelling and how cinema can be used to uncover historical scope. His The Birth of a Nation (2025) is the centerpiece of the program. It is a deconstruction of D. W. Griffith’s famous 1915 film The Birth of a Nation, which many critics and filmmakers consider the beginning of modern cinema and which introduced racist stereotypes that have plagued “entertainment” to this day. Douglas frees you from the pain and confusion some of these images evoke, demonstrating both the sincerity of feeling and the artificiality inherent in any narrative. — Hilton Als

Sourse: newyorker.com