Should a principled civil servant continue to serve under a morally bad regime? The question has special urgency when the civil servant is helping to run the suspect regime, keeping its leader from going deeper into error. The anonymous author of Thursday’s Times Op-Ed has answered this conundrum in a peculiar way: decrying the regime’s ills while staying in his or her post. The dilemma he or she faces would look familiar to Roman Stoic philosophers in the age of Nero, especially Seneca the Younger, who wrestled with it himself for fifteen years and never found a solution.

The Op-Ed author is not just a witness to the moral shocks of service under President Trump but an agent of resistance. The essay describes daily interventions to prevent Trump from acting on his worst impulses, thereby protecting the state and, indeed, the entire global order. “We want the administration to succeed,” he or she declares, even while attacking the “amorality” of its leading member. It’s a delicate task to separate Trump from his Administration. The Op-Ed writer does this by implying a distinction between rational impulses—policies and agendas—that define the latter, and the violent emotions of the former.

By strengthening the White House’s rational side, the author hopes to rein in the irrational—a role that the ancient Stoics, with their firm belief in the power of reason to promote moral virtue, would heartily endorse. Stoicism, framed in the Greek world as a path toward personal happiness, became, under the Romans, an increasingly political creed as the early emperors expanded their powers. Autocracy forced many into tough ethical choices, and Stoicism offered guidance, often to the detriment of the autocrat.

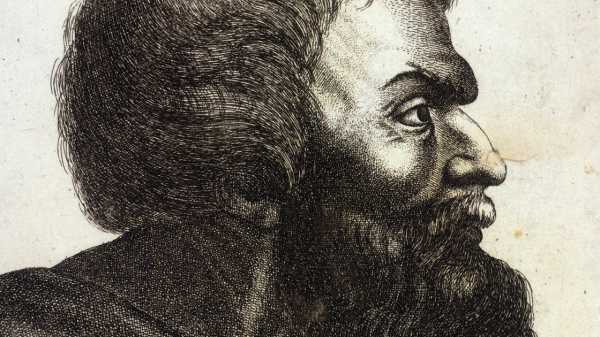

Seneca the Younger was already Stoicism’s chief Roman spokesman when he became tutor to an autocrat-in-training, a thirteen-year-old soon to be known as Nero. After his accession, at the age of seventeen, Nero began assaulting and raping Roman citizens on drunken nocturnal sprees, trusting in disguise and his imperial troops to protect him. In policy matters, he proved obtuse, recommending, in one of his first initiatives, a blanket cancellation of all trade imposts.

Nero’s proposed amnesty on trade taxes runs exactly opposite to Trump’s tariffs, but the reactions of their advisers form a close parallel. “Having first greatly praised the greatness of his mind, the senators held him back” by showing that such a move would bankrupt the state, Tacitus, whose Annals preserve a harrowing record of Rome under the early Caesars, reports. And chief among those senators was Seneca, Nero’s most trusted adviser. Together with a political ally named Burrus, Seneca was directing the rational wing of the palace, leading a shadow administration much like the one described by the Times Op-Ed writer.

The stakes of Rome’s court politics ran far higher than ours, in that emperors served for life terms and could put to death those they deemed disloyal. Yet we can perhaps translate impeachment to assassination and firing to forced suicide. Neronian Rome had already seen palace insiders rise up to dismiss their leader, by killing him—Caligula was disposed of in this way, a generation before Nero—and had also seen high officials open their veins, on executive order, after being accused of betrayal. These choices were stark, but, then as now, a middle path offered itself.

Repelled though he was by Nero, Seneca knew that the emperor would be in a far worse condition without him. Early on in his reign, Nero became enraged with his domineering mother, Agrippina, and, in moments of drunkenness or paranoid fear, demanded her death. The cost of killing this revered and powerful woman, as Seneca understood, was perilously high, so he talked the youth down from this murderous mood—much as Trump, to judge by reports, has been talked down from firing the special counsel, Robert Mueller. Seneca was, as the Op-Ed writer puts it, “the adult in the room” in these tense episodes, quite literally in a case in which the emperor, in modern-day terms, was still a legal minor.

While serving by Nero’s side for a decade, Seneca kept up his pursuit of Stoic wisdom. His essays from this time, many still extant, extoll the virtuous life available through reason and correct moral choice. Critics accused him of hypocrisy, and still do so today, but the Times Op-Ed writer helps illustrate the complexity of Seneca’s position. To abandon the role of rational steersman, as some have urged the Times author to do, is to leave the regime more at the whim of its worst impulses, especially if, as we might expect, any replacement would have less ability to exert influence. So Seneca continued to serve, and to keep silent about the turmoil inside the palace, even while striving to appease his own conscience through his ethical writings.

When the chance came to help kill Nero, Seneca demurred—though he was ultimately linked to the conspiracy anyway, and forced to take his own life. By then, the emperor had murdered his mother, and several other family members besides, and had become delusionally attached to a career as a performing singer. The horrific Fire of Rome, in 64 A.D., may have been started by him, or, at least, such was widely believed at the time. Yet Seneca still supported the imperial system that put a Caesar in place with the expectation that he would reign until death, then pass on power to a legitimate heir. The assassination of Caligula had shaken that system’s stability. A second such killing, within three decades, might well topple it.

The Times writer describes a similar train of thought with regard to invoking the Twenty-fifth Amendment as a way of deposing Trump. “No one wanted to precipitate a constitutional crisis,” the author relates, referring back to the early days of the Administration, when such a move was contemplated. Surely this amendment was added to the Constitution to prevent, rather than cause, a crisis, but the author’s meaning is plain. Any removal of a chief executive destabilizes the structure over which he or she presides. The results might be more painful, in the long run, than his or her policy errors. Especially if those errors can be contained and restrained.

In Seneca’s last hours, as he prepared to open his veins, he bequeathed to his friends “the template of his life” as his only legacy. It’s a template no one would choose to follow, knowing how Nero befouled it. But those today who have little choice, who labor to save the state from the whims of a mad monarch, may take comfort in knowing that they are not alone.

Sourse: newyorker.com