Here are some of the things that you will not find if you go looking for traces of the Soviet Gulags: memorials at every known execution site, museums on the ruins of camps, accurate documentation of what happened to the still uncounted numbers of people who disappeared, a widely accepted story of the terror. Most of all, what’s missing is a reckoning, an attempt to comprehend the incomprehensible. How do you locate what’s not there?

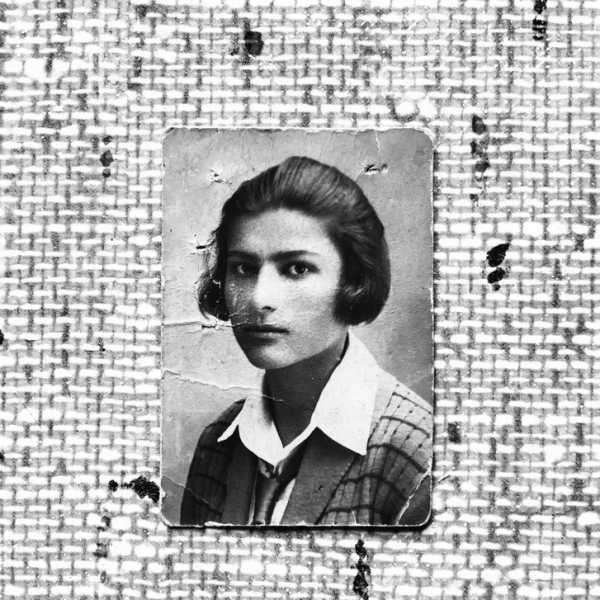

The sole surviving image of Nina Delibash, who died in 1937 in the Solovetsky camp.

The photographer Misha Friedman and I travelled in Russia in 2016, looking, as we put it in the subtitle of a new book, “Never Remember,” “for Stalin’s Gulags in Putin’s Russia.” We wanted to document memory—or the lack of memory. We began in places where I had reported two decades earlier, when memory activists, then often with the aid of local officials, created memorials or museums. We wanted to see how those sites had changed in the twenty years since, as Joseph Stalin’s image was being burnished—to the point that he now consistently tops polls asking Russians to choose the greatest man who ever lived.

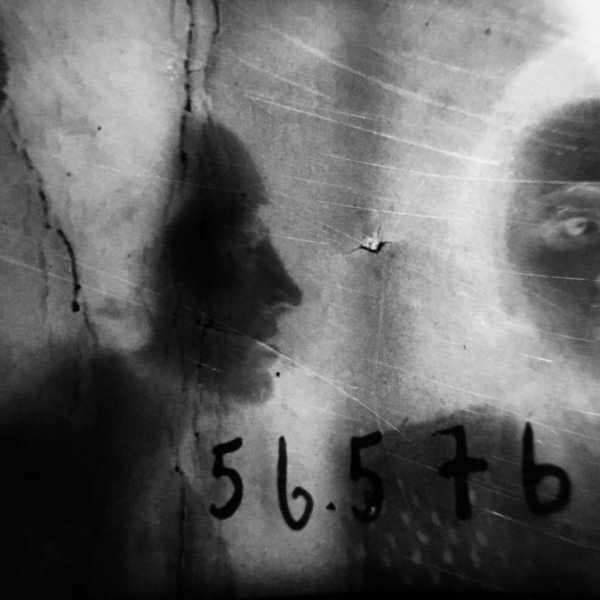

The People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (N.K.V.D.) mug shot, Memorial archives, Saint Petersburg (fragment).

In the Kolyma region, in the Russian Far East, where the harshest of the Gulags were, our guide was Inna Gribanova, who had taken me around on my first trip to the area, in 1998. Back then, she was a recently retired geologist in her mid-fifties, a recognizable type of Russian memory activist: after a quarter century of living in the land of the camps, she had become obsessed with them during perestroika. When the prospecting jobs dried up and the region emptied out, she stayed. She organized a permanent exhibit in a local museum in her village of Ust-Omchug, and eventually, she hoped, she would get monuments to Gulag victims erected in the village and farther out, at the site of one of the most infamous camps, Butugychag.

N.K.V.D. mug shot, Memorial archives, St. Petersburg (fragment).

Gribanova is now in her mid-seventies. Her one-room exhibit is still there, and the monuments still are not. The last of the Gulag survivors who settled in the area have died, and their houses—they had lived compactly on the outskirts of the village—were washed away by a flood, a few years ago. That was a spring of heavy water, which also washed away what had passed for an access road to Butugychag and rearranged the landscape of the camp itself, so that, as we hiked there, we kept finding ourselves on top of camp structures or, suddenly, inside what remained of them.

But the biggest change was in Gribanova herself. She had now come to think that tales of the horrors of the Gulag were overblown. Sure, conditions had been terrible—but most of the people in the camps, she now believed, were real criminals. The execution figures published by official archives in the late nineteen-eighties—documents that showed that during the Great Terror thousands of people were executed every day—were probably exaggerations. She also told me that she had voted for Putin: she’d had enough of always being in the minority.

A photo of the poet Evgenia Mustangova (a pseudonym referring to her mane of hair), who was killed in Sandarmokh in 1937, was made into a small memorial plaque at the site; it has since been repeatedly vandalized.

She didn’t glorify the Gulag or Stalin, and neither had she fully come around to the eggs-get-broken-when-an-omelette-is-made view of history. Instead, a cacophonous kind of memory fatigue seemed to have settled in for her. This was what we found everywhere we went: even where memorialization efforts existed, as in the Gulag Museum, in Moscow, they lacked coherence, passion, mastery.

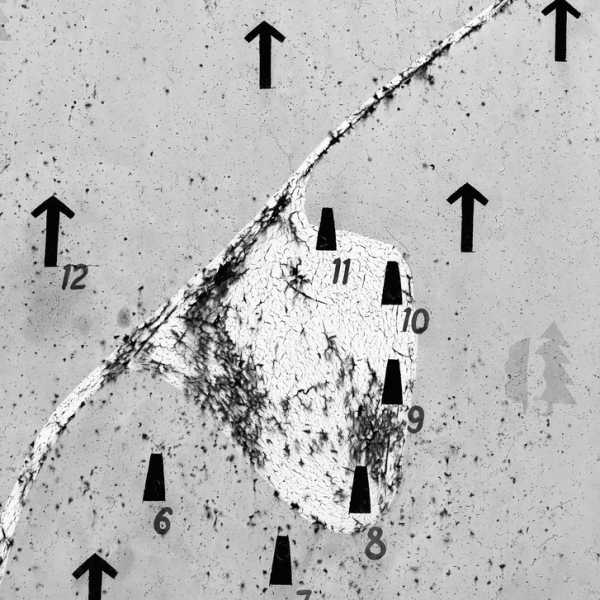

A burial map in Sandarmokh, where thousands were executed during Stalin’s Great Terror (fragment).

In St. Petersburg, we talked with Irina Flige, one of the most prominent memory activists in the country. When I told her that we were making a book about forgetting, she told me that I was wrong. She said that we had both been wrong many years before, when we thought that activism like hers was part of a larger process of remembering. Remembering was only possible when the past was past, she said. This hadn’t happened. Without remembering, there could be no forgetting. So, we were making a book about absence.

Perm-36, a Soviet forced-labor camp.

The Mask of Sorrow monument to victims of the Gulags, Magadan, Russia.

Butugychag Corrective Labor Camp, Magadan Oblast, Russia.

Detail from sculpture garden, Moscow, Russia.

Putin, Stalin, and Lenin impersonators, Red Square, Moscow.

A monument to victims of totalitarian terror, Moscow, Russia.

A scene from Sandarmokh, Republic of Karelia, Russia.

The harbor of Magadan Oblast, Russia.

Butugychag Corrective Labor Camp, Magadan Oblast, Russia.

Sourse: newyorker.com