“A poem is never done,” the writer Sandra Cisneros told me in July, over dinner at La Posadita, a restaurant in San Miguel de Allende, the Mexican city where she’s lived for almost ten years. Wearing a black-and-white huipil and her hair in two small, high buns, Cisneros ordered platters of fideo seco and nopales for the table. We had met to talk about her new poetry collection, “Woman Without Shame,” just out from Knopf. Though it’s been twenty-eight years since she’s published a book of poems, she’s never stopped writing them. “I’d throw my poems under the bed, like Emily Dickinson,” she said.

The sixty-seven-year-old Cisneros is the author of short stories, personal essays, novels, and three previous poetry collections. But she is best known for “The House on Mango Street,” a semi-autobiographical novel in vignettes that conjures a hardscrabble childhood in nineteen-sixties Chicago. First published by Houston’s Arte Público Press in 1984, and reissued by Vintage in 1991, it has become a coming-of-age classic, one that’s read in classrooms across the country and has sold more than six million copies. As Ricardo Ortiz, an English professor at Georgetown, told me, it helped make Cisneros an “indispensable voice.”

The only daughter of a Mexican upholsterer father and a Mexican American mother, Cisneros grew up with six brothers in Chicago’s West Side, a neighborhood so divided by racial and income inequality that, in 1966, Martin Luther King, Jr., moved into one of its slum tenements in protest. Throughout Cisneros’s childhood in the sixties and seventies, she and her family regularly went back to Mexico. Cisneros expressed her sense of dislocation by writing poems in her bedroom, whose door didn’t close, leading to continual interruptions.

Cisneros attended Loyola University Chicago, and, in 1976, she entered Iowa’s poetry program, where she studied under Donald Justice and Louise Glück, learning alongside Joy Harjo and at the same time as Rita Dove, both future Poet Laureates. Iowa’s poetry and fiction programs were separate duchies, but Cisneros merged the disciplines by writing prose poems. “It was a new form, but Donald Justice thought it was a waste of time,” the writer and historian Paul Alexander, a former classmate, said. Back then, teachers admired confessional poets such as Robert Lowell and Anne Sexton. “We had no voice,” Harjo said, describing her and Cisneros’s feelings of being outsiders at Iowa. “Culturally, it was sideways. . . . We come from places that are land-centered, Indigenous. Our relationship to land and language is essentially different.” Cisneros has said that she felt “homeless” at Iowa, and, although she went on to teach, she never found a permanent place in the academy.

While Cisneros was at Iowa, she started writing what would become forty-five lyrical vignettes—a book she titled “The House on Mango Street.” Influenced by the experimental Latin American Boom novels, she wrote the book in the voice of Esperanza Cordero, who observes the poverty surrounding her Chicago family. “Dead cars appeared overnight like mushrooms,” one passage reads, describing a vacant lot where she and her friends play. Reading “The House on Mango Street” has become a rite of passage for many Latinxers. David Bowles, a Texas-based Chicano novelist, encountered it as a child and felt recognized. “My mother and my brothers and I had lived several years in Section 8 housing,” he said. “It made me feel seen.” The Latina writer and artist Carribean Fragoza studied it in fourth grade, during a summer writing camp, a moment when she remembers being “surrounded by white kids for the first time.” The book helped Cisneros win, among other prizes, the Lannan Literary Award, the American Book Award, and a MacArthur “genius” grant. The same year she won the MacArthur, Cisneros started teaching a class in San Antonio that developed into the Macondo Writers Workshop. Now in its third decade, Macondo offers workshops to a diverse student body on subjects ranging from young-adult literature to translingual poetics.

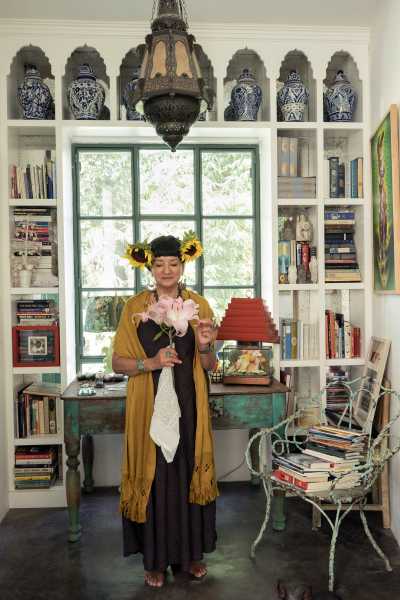

Cisneros’s home in San Miguel’s San Juan de Dios parish is named Casa Coatlicue, after the Indigenous goddess, and Latina archetypes such as Coatlicue and La Llorona echo throughout her work. Cisneros, along with writers such as Gloria Anzaldúa, Ana Castillo, and Cherríe Moraga, was an integral part of a late-twentieth-century Latinx movement that celebrated the subversiveness of Indigenous folktales. She was one of the first Latina authors to write books to mainstream publishing success that feature abused women, and today her influence can be seen in writers such as Natalie Diaz and Reyna Grande, whose complex poetry and memoirs limn violence in Native American and Latinx communities. “Discovering Sandra’s book [“The House on Mango Street”] was a revelation,” Grande said, in an e-mail. “She gave me permission, and her bendición, to embark on my own writing journey.”

Cisneros’s success, and her support of programs such as Macondo, have given her a totemic reputation. “It’s like Sandra’s existing in this heaven, this other space,” Fragoza told me. In conversation with Latinx writers, I heard numerous tales of Cisneros’s magnetism and outsized generosity. The Chicana novelist Helena María Viramontes said that when her husband was ill, Cisneros invited the couple to her house. Speaking with emotion in her voice, Viramontes recalled, “She read to us as a present. It almost chokes me up.”

Cisneros’s magnanimous gestures occasionally backfire, as when she blurbed Jeanine Cummins’s 2020 book, “American Dirt,” a thriller about an Acapulco woman whose family is murdered by a cartel kingpin. “This book is not simply the great American novel; it’s the great novel of las Americas,” Cisneros wrote. After it came out, the book was widely criticized for its racial stereotypes. Backers such as the actors Gina Rodriguez and Salma Hayek and the poet Erika L. Sánchez walked back their praise of the novel. But Cisneros refused to retract her endorsement, inciting viral criticism, especially in the Latinx community. Fragoza said Cisneros’s blurb is a “betrayal” that “revealed some serious disconnections between Sandra and writers today, with Sandra existing as the untouchable queen of Chicana Latinx literature, and the rest of us are just bottom feeders, trying to get into publishing.”

I asked Cisneros about such responses, and she said that the reaction to “American Dirt” “was as bad as the extreme right that bans L.G.B.T.Q. books.” Perhaps candor and contention are to be expected from a writer who regularly takes up taboo subjects ranging from poverty and violence to female sexuality.

Cisneros’s fearlessness runs through “Woman Without Shame,” whose poems capture her solitude, erotic longings, and life in Mexico with rich language and sharp humor. I spoke to her in a series of interviews in San Miguel de Allende, and in subsequent phone and text conversations. The following has been condensed and edited.

“Woman Without Shame” almost reads like a diary—it’s full of sly references to past lovers, and vivid depictions of turning points in your life.

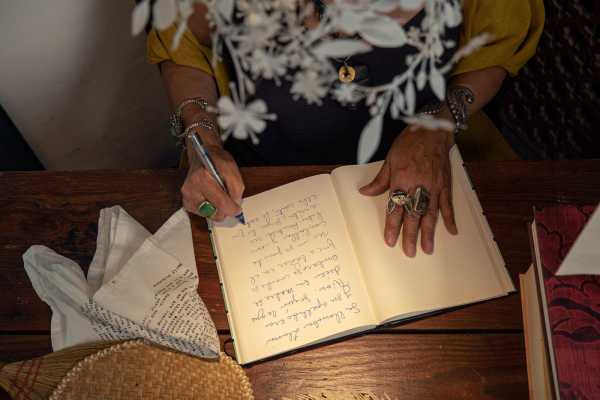

It’s more my journal than my journal. My journals are like hieroglyphics. If you look at my journal, you won’t understand a phrase or a name or a quote. It won’t explain where things come from. It’s only when I write poetry that I explore.

There’s an incredible frankness to the lines throughout, especially when it comes to writing about love and sex. In “Making Love After Celibacy,” you write, “I bled a little, / Like the first time. / There was pain. / . . . / And a winged bliss / Just beyond reach.”

If you don’t tell your most vulnerable secrets, someone will tell them for you, so you’d better get them out there before you die. I don’t want to have any open secrets.

You have often said that you’re “nobody’s mother and nobody’s wife.”

I have a poem titled “Neither Señorita nor Señora” about why I didn’t marry. Some people who come into our lives are exploding cigars, and some people are North Stars, and some people are both. I am very grateful for all my exploding cigars, because if I’d stayed with them I’d be a very angry woman. I’m glad those relationships didn’t work. They were very painful at the time, but in retrospect, you know, it’s like having your hand caught in a car door. It takes a long time for your hand to heal, and it takes years before you can look back and realize, What was I thinking? You can see that when you’re older. You think, Oh, I see the pattern now.

In “You Better Not Put Me in a Poem,” you make a catalogue of your lovers, their physical attributes and bedroom proclivities. What gave you the idea?

There was this man—he was one of the early lovers in my life—and he told me when I was undressing, “You’d better not put me in a poem.” I was twenty-one or twenty-two. I was so young. I didn’t know what he meant. It took me decades to understand. I was in my fifties, and I was making the bed—I get a lot of ideas when I’m making my bed—and I remembered him saying, “You’d better not. . . . ”And I thought, What did he mean by that? I finally figured it out.

And?

I thought, Oh, he wants me to write about him. I said, O.K., but how can I do that? I don’t want to disrespect people and be vulgar. So I said, O.K., well, what if we mention everybody and then you don’t know who it is? I thought it was going to be a funny poem, and it flipped, because that’s where poetry takes you. I didn’t know it was going to be a twelve-page poem. It’s fun reading it out loud, but I don’t get to read it out loud very often because children always come to my readings. I always take an age-appropriate roll call before I begin.

You’ve held a writing workshop with the novelist Ruth Behar, where you focussed on women’s voices.

We call our workshop the panocha—vagina—workshop. We need to write from that place as women. We shouldn’t have nicknames for our sexual parts. They teach us to say “down there,” “you know what,” “vajayjay.” What is that about? It must be powerful if people are afraid of it. So I just thought of all the ways that we’re censored and made to be ashamed of our most powerful parts. That’s where our writing should come from. I didn’t want to shock anybody. I just wanted to write down the things I think. And not be ashamed.

There are many spiritual threads running through the book—Buddhism, Catholicism, Indigenous gods and goddesses . . .

When I talk about religion, I have to be careful, because people have a lot of baggage, including me. You may doubt the existence of God, but no one doubts the existence of love, especially those who have never been in love. That takes a lot of faith.

In one poem you write, “It Occurs to Me I Am the Creative / Destructive Goddess Coatlicue.”

We’re all Coatlicue as women writers. I mean that we’re creative-destructive beings. For one thing, we have to be really furious to guard our time and space. She was that big square column of a goddess who was so horrific to the Spaniards that they unearthed her and then reburied her.

Like Sharon Olds’s “Stag’s Leap,” “Woman Without Shame” interrogates the experience of being an older woman with desires. Does it feel like a taboo subject?

Yes! They castrate us by giving us ugly underwear. Somebody should give older women wonderful lingerie. For women who are older, there’s nothing flattering. Why can’t we wear beautiful things on our bodies, even what’s not seen? So that we walk as strong women, so that we come on stage feeling like, Hey, I’m a chingona! Powerful!

I have the most intense erotic dreams now. I have a sense of taste in my dreams, I have soundtracks, I have original works of art. It’s like the movies but better, ’cause I’m in it. My best dream was that I put a credit card down on a reception desk in a fancy hotel and I said, “I’d like a room with a man,” and they said, “O.K., we’ll send him right up.”

Isn’t that a great dream? Why do men have to have all the power? It’s like they think women over sixty don’t have sexual desires, sexual imaginations. I think of Cavafy, who, when he was older, wrote all these sexy, erotic poems about his youth. I feel like I can explore it through my fiction and my poetry and through my imagination and my dreams and self-love. I don’t have to be stuck waiting for some man to knock on the door.

The poems look back on your romantic history—what strikes you most about it?

In “The Ballad of the Sad Café,” Carson McCullers talks about people being the lover or the beloved. I’ve always been the lover, never the beloved, but I don’t feel sad about it. . . .

I had quantity but not quality. I didn’t have long relationships, and they were long-distance, but when you’re a writer you like having long-distance relationships because they don’t get in your way. It’s hard to live with someone, and it’s hard to live alone. But I prefer living alone.

What was your most significant relationship?

The great love of my life was Chamaco.

Is that one of your dogs?

Yes. You know, he loved me like no human being has ever loved me. Sometimes the great love of your life has four feet and a tail.

Cisneros, at her home in San Miguel de Allende.

You grew up in Chicago and are now living in San Miguel de Allende, and you’ve made many moves in between. Can you estimate how many places you’ve lived?

I had lots of jobs—I’ve been working since I was fifteen. I was a migrant professor. I went into the academy reluctantly, because I didn’t feel like I had anything to teach—that’s self-racism, where you’re both victim and a self-perpetrator. You believe you are less than others because that’s what you’ve been taught. I was at Cal State, Chico, for a year, and then I went to Berkeley. I taught poetry at an alternative high school. San Antonio, Austin, Chico, Berkeley, Irvine. I lived in Albuquerque, Provincetown, Chicago—about nine places, but that doesn’t count when I was at Iowa. Ten places.

Did you consider each of those places home?

No.

Why?

I would just go to work, and the key was lowering my overhead, so I could write. I lived in my brother’s guest bedroom in Illinois.

So eleven places. How did it feel to be so . . .

Transient? How does it feel to follow your husband around for his job? My husband was writing.

You ended up staying in San Antonio for a long time.

I didn’t love Texas, but I loved that it was affordable. I had an apartment for two hundred dollars. . . . And then in the early nineteen-nineties my agent told me I should get a house.

I thought, Really? You think I can earn that much next year? Somebody recommended that I get water from Woman Hollering Creek—it’s a real creek. I went to this house and circled it and sprinkled it with water and prayed to the Virgen de Guadalupe and said, “If I get this house and the bank approves, I will put up a tile plaque and thank you.” And the neighbors who were watching the house said, “Can we help you?” I was doing Mexican voodoo. I said, “I’m thinking of buying this. I’m checking out the garden.” I was sprinkling holy water, but how could I say this to a white man?

I paid a hundred and forty thousand dollars for it back in the early nineteen-nineties, and the back yard went down to the river. It was amazing. A lot of things in my life are beyond my imagination, and one of them is owning your own house.

You said that your father wanted to buy you and your brothers a house?

He was worried about us. He wanted to help us, but my father didn’t help me buy my house. I did it all with this [acts out writing], and that’s the amazing part. He had wanted me to get married. And when I won the MacArthur, in 1995, it was the big lotería, and my father couldn’t believe it. He said, “Mija, don’t get married, he’ll just take your centavos.” That was to me, like, Wow. I had this selfish dream, let my father live long enough to understand what I do. And the universe gave me that.

There’s a poem in “Woman Without Shame” titled “After a Quote from My Father,” which chronicles household chores and ends, “None say: / Look at the moon. / Write poetry. / Take you time, mija. / Take you time.” You seem like you were very close to your father.

When I wrote about my father, I had to think, How did he get to be such a loving father? That’s so unusual. . . . The best thing about my MacArthur is that it came before he had his final terminal announcement, and I could stop writing and be present. I could go with him to the hospital, I could watch “Sábado Gigante” and just sit there. I was so depressed that I bought a spool of white-cotton embroidery thread, and I would crochet in the dark by the light of the television next to him. Then I would take it apart and start over again, like Penelope.

One of your last books before this was “Caramelo,” a novel about a large family that travels back every year to Mexico City, much like you and your siblings did with your parents.

I’m a miniaturist, and I wrote a little story, and it got bigger and bigger, and it became a novel. I wanted to understand my father, a man who served in the Second World War without understanding or speaking English. If you don’t write a story like that down, it’ll be like it never happened. He doesn’t have Ken Burns trying to tell his story.

It’s been twenty-eight years since your last book of poetry came out. Were you writing poems all along?

I wasn’t writing them every day. I just wrote them when I had to. If I didn’t have poetry, I would have to be on Xanax or Prozac. It’s my medicine.

You’ve said that you’d “just start things and throw them under the bed, like Emily Dickinson.” Is Dickinson a role model for you?

Yes. One of the things I learned from Emily—Miss Emily, I should say with respect—is that you don’t have to publish in your lifetime, but you have to write. I felt so exposed after “My Wicked Wicked Ways” came out, in the nineteen-eighties, and it made me question why we have to publish—where does that come from? Just because I have a uterus, I don’t have to have a child, and just because I write poetry, I don’t have to publish it.

Was that idea freeing?

I discovered a poetic truth, that you have to write as if what you had to say is too dangerous to publish in your lifetime. Then your ego gets out of the way, and you allow the light to come through you, the blood jet that Sylvia Plath talked about. You write from a more honest place.

Are you writing poems at the moment?

I was thinking of another poem I needed to write: “Tips for Touring.”

What would it be about?

Just make a list. Make sure you tip the woman who makes your bed more than the man who carried your bag for five seconds—she works an hour cleaning your room, and she could be you. Make sure you thank everyone. Things like that.

There is a tradition of poems that give advice. Hesiod’s “Works and Days”—it goes back really far. You have one poem in the new collection called “Instructions for my Funeral”: “No jewelry. Give to friends. / No coffin. Instead, petate. / Ignite to ‘Disco Inferno.’ ”

I decided that it wasn’t enough to put the instructions in my will; it would be too late. But if I put them in a poem everyone would know.

You’ve won many awards. Is that meaningful to you?

The only one I tried to get and wanted was the N.E.A. [the National Endowment for the Arts], one in poetry and one in fiction. I applied every year, like doing your tax forms. I had very low aspirations. My aspiration was that I would get blurbs from the writers I admired—Studs Terkel, Gwendolyn Brooks, Eduardo Galeano, Dorothy Allison . . . but especially Studs Terkel.

Why him?

He’s my literary ancestor, collecting stories and oral tales, and he’s also significant personally: my mom got educated listening to his show. She would ask for the books that he mentioned—“Call Richard from Guild Books, and get me that book from some guy from Chile.” “Who, Pablo Neruda?” “Yeah, him.” She went to the university of Studs Terkel.

The poem “My Mother and Sex” includes the line: “She lived alone/ In a house full of lives.”

My mother was unhappy, she was frustrated—she was in a marriage with someone who didn’t like to read. My father was sweet, but he wasn’t her soulmate.

Your former classmates at Iowa describe you as very quiet. Mary Jane White said that you “were very petite, tiny.” She told me, “I always thought of her as little Sandra, and she grew up into this big voice.”

In Iowa I was ashamed and afraid. As soon as you opened your mouth, they shut you down, and you learned how to shut up.

But then Lan Samantha Chang, the current director, invited you to speak there in 2017. White said that you filled Macbride Hall’s auditorium with thousands of people, and signed books for an hour and a half.

I was there to talk about my experiences, and it meant a lot to me. I remember that the president and the president’s wife at the university went to one of my lectures, and I said, “I’m talking more in this lecture than I did in two years as a student.”

Can we talk about your blurb for Jeanine Cummins’s “American Dirt”?

For me, to fight against Trumpism was to blurb any book about the border, so that was one of twenty-six books I blurbed that year. And I did it, and what do I get? Even if I was hyperbolic, I knew that book would be read by people who weren’t in the choir. I didn’t know what the advance was. I knew she did her homework, and she wrote a thriller. People got mad. A memoir will not get you a million-dollar advance, or if you write poetry—come on. You want your book to get sold? Write a thriller. Write a Y.A. book.

It made me really sad, because I saw my own people acting worse than the Trumpers with one another and with other writers. I said, “No, this can’t be my community. This can’t be the people who are asking for human rights for immigrants and yet are cruel to another writer.” And she’s on their side. Everybody was working from a place of pain—the author, the people who felt “Why didn’t I get that deal?,” and me, who feels no writer should be bullied. But at the time people are reacting and putting a lot of vitriol out there and bullying another writer who took how many years, how much footwork to go out into the field and interview immigrants, refugees, people who shelter them. She did her homework, and I just felt like they treated her like trailer trash, like she was nothing, and she’s their ally. That she sold it for a big amount? Good for her.

You weren’t the only one who blurbed the book.

What was real chickenshit was some people blurbed the book and retracted it. And the people who were the most up in arms about it didn’t even read it or didn’t finish it. I was so sad. I had to go to the Oaxaca coast and just walk and think about it. It was so painful. It still pains me. I’m still angry, and I think that’s why I’ve hesitated talking about it, because we shouldn’t speak when we’re angry. I’m seeing it clearer now. I see that everybody’s acting from a wound, all the key players are acting from wounds, and the ones that attacked me the most are angry that I’m not reading their work.

Any book that deals with the issue of immigration and the border I’m going to blurb.

Was there any merit to the criticism directed at you?

I know what I am, I know what I do, and so I don’t have any problem. I can sleep well at night. But I didn’t put vitriol out there.

I think the best response was given by Louise Erdrich. I attempted to write something, but it wasn’t complete because I was still in a place of deep sorrow and betrayal. I felt so disappointed and betrayed by my own people, and I felt so ashamed of the way they were acting. There’s a beautiful line of Luis Alfaro’s. He hits himself on the chest, and it’s the refrain: “Where are my heroes? Where are my saints?” I was searching for someone to make it clear, and I should have been the one to do it, but I could not, so it was a disappointment in myself.

It sounds like it’s still painful.

I’m going to write an essay, “Bringing Up the Dirt.” Because I need to find a place to forgive myself and forgive everyone that was involved. I don’t want to be connected to anyone with rage, and the only way I can do that is by writing. The way I can try is by seeing them as wounded, understanding that their vitriol is at the wrong target. Each person, including the author, has suffered terrible shit, but unfortunately, you know, the writers haven’t written through their pain to transformation. I think that the author did, and she was able to write that book. But I think she stepped on some deep problems by things that she said about defining herself as Latina—that was, like, a stretch. [Cummins has identified as both white and Latinx.] I didn’t know anything about that. I just got the galleys. It was just like any galley: we read it blind.

Let’s talk about San Antonio. You had been there for many years. What made you decide to leave?

My roots dried up. I remember locking up my office and going up to my house, and I thought, I own three houses: the house for Macondo, my office, my house. Why am I not happy? My time here has ended.

Why? What happened?

I felt not appreciated. I struggled every year to put Macondo together, but it is very hard to be an administrator and a writer, and no matter what I did, no matter how hard we worked to make Macondo as perfect as we could, there was always a malcontista. There would be fighting and problems. I thought, What’s the point? Fifteen years is a good run. [Macondo is still operating out of San Antonio, but Cisneros is no longer in charge of its day-to-day administration.]

I read that the original Indigenous name of San Miguel de Allende was “water of the dogs.” You visited before you came and saw a sign?

Yes. . . . I stayed at an Airbnb, and these white cranes were in the trees. According to Indigenous belief, they take your prayers to Heaven. It was like an omen of home, but I didn’t understand it. And then I woke up in the middle of the night—it must have been four in the morning—and this message came into my head and it said, “You are not your house.”

And I understood that I was so deeply immersed in the future of my house in San Antonio—I don’t have children, I’m going to leave this house for future artists to write here, that will be my greatest legacy—but if I stayed there I would never write another book. I arrived as a small fish in a small pond, but I became a big fish in a small pond, and when you grow too fast it reminds people that they haven’t moved. I just felt that if I stayed in San Antonio, I could work my ass off and nobody would be happy or appreciate it. Now they miss me.

So you decided to move to San Miguel de Allende.

Yes, I came here. I didn’t know the town was colonial and had a very colonial writing program, all white and expensive and structured in a very colonial way. I didn’t realize it was San Miguel apartheid, and, when I told them that, they were offended and shocked, so I lost my enthusiasm for the book fair. I’m going to be onstage there next spring. I’m only going to do it if I can donate my honorarium to the Spanish-language portion of the fair, so, you know, that’s my way of making my peace with them. I came because this is the land of my mother’s people. I wanted to investigate those roots.

Your grandfather fought in the Mexican Revolution.

My paternal grandfather did. He was a Federalist.

And your mother’s family is from Guanajuato.

Yes, they fled because at that time there were, like, three caciques all fighting for power. This was Pancho Villa and [Álvaro] Obregón and the Carrancistas—all of these different factions. The revolution had multiple sides in Guanajuato. There was a great deal of violence in 1915, and on my mother’s side they were working land that didn’t belong to them.

I noticed your house in San Miguel is called Casa Coatlicue.

I had to think of a name for my house. Well, what’s the goddess that really personifies a writer’s life? I couldn’t think of any goddess stronger than her. And I wanted people to keep their distance—I don’t want “mi casa, su casa.” I dreamed of a high wall. I just feel like, at this point in my life, I don’t want everyone to come into my house. I feel very private in a way I wasn’t in Texas.

You mean in San Antonio?

Yeah, because too many people came to see my house. I didn’t mind the librarians and students, but, you know, I have to get my work done. I’m running out of time.

Is this it? Do you think you’ve finally found home?

I think I have one more house in me.

Where would it be?

Oaxaca, maybe. Or some other country. I don’t know. There are a lot of retired people here, and I’m not retired, and I’m never going to be retired, and the kind of work that I do is so antisocial and anti-San Miguel, because San Miguel’s about margaritas on the terrace. I’m not there yet, and I’ll never be, because I always hope to be writing something. I hope my last breath is: “Write this down.”

In 2010, Tom Horne, Arizona’s superintendent of public instruction, shut down the Tucson school district’s Mexican American Studies (M.A.S.) program under H.B. 2281, which prohibits classes that “advocate ethnic solidarity.” Administrators pulled books written by James Baldwin, Junot Díaz, and Jimmy Santiago Baca. They also stripped the classrooms of “The House on Mango Street.”

Students were becoming empowered by who they were, and people in positions of power were threatened by that enlightenment. And if you look at the original treaty, when they purchased Arizona, people spoke Spanish and it was part of the agreement that that would be respected.

The M.A.S. ban has since been struck down by a federal district court under the U.S. Constitution’s equal-protection clause and the First Amendment. But now, with critical-race-theory bans, this kind of censorship is happening again.

Of course. In Fredericksburg, Texas, librarians are being vilified for protecting the freedom of reading books. One of the things that I think we should do is buy these books and give them to young people and librarians. Give them to a poor library, or buy a set and give them to a young person. Something that we could all do is buy one book.

People are frightened; they feel and have been feeling for a long time that the world is changing in their lifetime. They fear sharing or losing power. In Texas, you’re seeing that politically. In the last twenty years, people on school boards feel frightened of alternative ways of being and sexuality and see those things in a fearful, negative way, as opposed to sexuality being a source of empowerment. That’s why I’m anticipating that my book is going to be banned in Texas. It’s a very conservative part of the world. When I moved there, I thought I’d dropped into nineteen-fifties America. I hope there could be some place for dialogue and communication, but I think that we’re not in a place where people are listening. They’re so polarized.

I believe in the power of the word and the ability of writers to make change. This is the time when we should be saying, “O.K., let’s put the poets and writers in the front lines.” We need them to be peacemakers and truth-tellers, because people feel distrustful of church and politicians—what are the poets if not the truth-tellers? Poetry is meant to heal and transform people. It’s essential for that. We don’t know how to address the public after Uvalde or El Paso or Sandy Hook. We don’t know how to say, “Send in the poets,” just like you send in the Red Cross.

Let’s go back to the beginning, to your biggest book. “The House on Mango Street” is being adapted as an opera. Who had the idea?

The composer Derek Bermel. You can hear a song if you Google “House on Mango Street” on YouTube. Derek wrote a suite, and he came here. We held a workshop. It was called “A Slice of Mango,” and we presented it to an audience. We’ve been working on it for about four years.

Are you changing it?

We’re bringing it up to current times. We’ve developed the themes and created an arc that’s essentially a very timely story. The opera allowed me to revisit characters and fine-tune it so that we could bring it into focus with 2022. It’s not frozen. Unfortunately, the issues are the same as when I finished it in 1982.

Someone at the film studio Gaumont is also writing a script, to make it into a movie.

“The House on Mango Street” is my oldest child, and as my oldest child he goes out and brings back the bacon for the rest of us. I just feel very pleased—it’s not my favorite book, but I’ve become very fond of it after working on the opera. I’m very pleased that it has the power to do the work that it’s doing.

You have a lot of projects going on at once. I know you collect and design textiles, too.

I’m doing a textile show. I’m a frustrated textile person. I’m collaborating with Nancy Traugott [a textile designer based in Santa Fe]. I met her at her store, and she proposed a collaboration. She said, “I want to add some poetry on my clothing.” I buy a lot of vintage, since I was a child. I gave Nancy this little white camisole I found in a flea market—it’s a hundred years old—as a present. I wrote on it with a sewing marker that washes out: “I dreamt I was dreaming and in the dream within a dream I saw my other life a pearl within a pearl an infinity of pearls.”

Are you working on any fiction now?

The novel I’m working on now is about a triangle, two men and a woman. To me, the real story of gay Mexico is: it’s all under the table. So many gay men are married to women, and that’s the only way they can be gay. I started it before [Barack] Obama called me to the White House. I knew that if I went, I would stop writing it, and that’s what happened. That was 2016.

When he gave you the National Medal of Arts.

And I told [my old publisher Norma Alarcón] I didn’t want to go, because Obama deported more people than any other President. And she said, “You have to go and represent.” So this is where fashion becomes political. I wore flowers in braids in my hair and my best Tehuana huipil and my cowboy boots and my mother and father’s picture and my mother’s Virgen de Guadalupe medal around my neck. I couldn’t talk. I thought my clothes would be recognized by Latinos, and that would be the way that I could communicate.

Why did you think you’d stop writing?

I knew that if I left my desk, I would not be able to get back to this novel for a long time, if at all. It’s like I swim leagues to the bottom of the ocean, and, if someone rings the bell, I have to swim up to the surface. It took me months to get to the bottom, and once I get back up I know it’ll be hard to return to the bottom of the sea. I’m not a photocopy machine that you can program, three copies on both sides. I can only say, “I’ll write, and let’s see what happens.” ♦

An earlier version of this article misspelled the name of one of Sandra Cisneros’s dogs.

Sourse: newyorker.com